Consumers in South Africa proceed to grapple with a high cost of living, significantly with the latest rising fuel costs. In the final a number of months, the price for one litre of 95 octane petrol (inland) has risen by 36.4%, from R19.61 in January 2022 to R26.74 (about US$1.60) in July 2022.

A combination of factors underlies this huge improve. One of the largest is the Russia-Ukraine conflict as the 2 nations are substantial players within the global commodities market. This is a concern for South Africa, which is very depending on imports of vitality merchandise.

The nation’s dependence on crude oil imports is instantly associated to the spike in home petroleum costs. The nation is a price-taker within the worldwide oil market. This exposes it to the volatility that arises from the imbalance between worldwide demand and provide of crude oil.

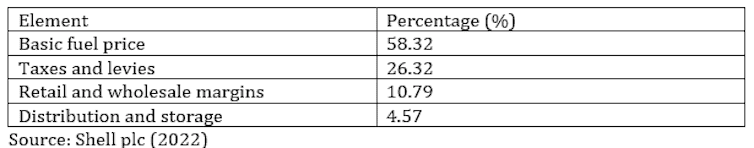

South Africa has a fuel levy which is a part of the retail price of fuel and a main supply of tax income. Broadly, the price of fuel on the pump consists of 4 components: fundamental fuel price (which is set by the worldwide price of crude oil and the price of transportation and insurance coverage); taxes and levies (mainly, the final fuel levy and the highway accident fund levy); retail and wholesale margins; and distribution and storage.

To take some sting out of the excessive fuel price, government reduced the final fuel levy by R1.50 per litre for April, May and June and by R0.75 for July.

The announcement of the momentary aid measures prompted calls from political parties and the public for a overview of the fuel price construction. This is on the again of continued will increase within the retail price of fuel. More are forecast.

Political events and a few economists argue that authorities levies are artificially inflating fuel costs, whereas authorities’s current responses are momentary and insufficient. Therefore, a long-term and workable resolution can be to decontrol fuel costs.

But in our view, whereas deregulation would promote aggressive pricing, it might additionally result in cuts in authorities spending or will increase in different taxes. Scrapping levies – or decreasing them considerably – would go away a R90 billion (US$5.3 billion)

hole in authorities income.

How then would completely different authorities coverage responses to excessive fuel costs have an effect on individuals’s livelihoods in South Africa? This article is predicated on the outcomes of a 2012 paper. But we imagine the findings are nonetheless related to the present debate.

In our paper we assessed the affect of three different coverage responses to excessive oil costs in South Africa on poverty.

The three situations

We used an analytical framework that enabled counterfactual and different coverage response experiments.

We used an energy-focused macro-micro model that

supplies a detailed analysis of the impacts of exterior shocks – equivalent to excessive fuel costs and different coverage responses – on poverty.

We assessed the poverty implications of three alternative

government policy responses to high oil prices in South Africa.

In the primary coverage experiment, shoppers had been assumed to take the total brunt of oil price will increase. We referred to this because the floating-price state of affairs, akin to finish price deregulation.

In the opposite two experiments the federal government was assumed to intervene and

compensate for oil price will increase by means of a price-subsidy mechanism primarily based on

completely different financing regimes. We referred to those as price-setting situations.

In price-setting state of affairs 1, the subsidy was financed by the federal government with the imposition of extra taxes on households and corporates. In price-setting state of affairs 2, the subsidy was partially financed with revenues from a 50% tax on the earnings of the artificial petroleum trade. In different phrases, a type of windfall tax.

The outcomes needs to be taken as giving a short-term perspective of the affect of

current oil price shocks. They reveal that the completely different situations or authorities coverage responses to excessive fuel costs would improve the measures of poverty. These are:

- the poverty headcount – the proportion of South Africans residing under the meals poverty line

- the poverty hole – the sum of money wanted to convey poor individuals to the meals poverty line or to assist them safe the requirements for survival

- poverty severity – the variations that exist amongst poor individuals relating to their stage of poverty.

Under the floating-price state of affairs, the poverty headcount, hole and severity elevated by 1.2%, 1.5%, and 1.6% respectively.

Of specific curiosity is the marginal improve in poverty measures underneath the price-setting situations in contrast with the floating-price state of affairs. This is as a result of for the federal government to subsidise fuel costs, it must increase taxes on households or firms.

The internet impact of those financing strategies can be a discount in households’ and corporates’ earnings and financial savings. This would result in a slight worsening of the poverty scenario. The decline in saving and funding underneath the price-setting situations would prohibit the nation’s progress, employment and earnings distribution views.

Outlook

Our analysis confirmed that the excessive oil price will increase poverty, and subsidising the oil price worsens the impact.

In addition, we discovered that the poorest households undergo the worst results, thus worsening earnings inequality.

An necessary message from this examine is that oil price shocks improve poverty and inequality, no matter whether or not costs are deregulated or subjected to regulate by means of a basic subsidy. Therefore, subsidies to protect the final inhabitants from oil price will increase don’t robotically scale back poverty and inequality.

It is, due to this fact, worthwhile for the federal government to search out simpler coverage responses – equivalent to focusing on poor and weak households and other people – as an alternative of a common subsidy response if its purpose is to scale back poverty and its severity.![]()

Margaret Chitiga-Mabugu, Dean of the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of Pretoria; Ismael Fofana, Director, Capacity and Development, Akademiya2063, and Ramos Emmanuel Mabugu, Professor, Sol Plaatje University

This article is republished from The Conversation underneath a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.