South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has lost the confidence of a key constituency.

Five years after ushering in a wave of business optimism that he’d revive an economy hobbled by industrial-scale corruption under his predecessor, executives are running out of patience with the 70-year-old leader. Economic stagnation spawned by record daily power outages, rampant crime, disintegrating infrastructure and foreign policy missteps is leading investors to the exits, with the rand fast-approaching a record low of 20 per dollar.

The business community’s growing disaffection with Ramaphosa’s administration was expected to be a topic of discussion at talks between his deputy, Paul Mashatile, and company executives on Friday evening. The mood going into the meeting was summed up by Investec Plc Group Chief Executive Officer Fani Titi.

“We are going nowhere fast,” he said in an interview on Thursday. “The government is disorganised. Totally disorganised.”

Business leaders raised concerns about issues affecting their constituents in their discussions with Mashatile, the presidency said in a statement after the meeting on Friday night.

“They urged the government to work with a greater sense of urgency in attending to the energy crisis, crime and corruption, and processing of applications relating to statutory obligations hindering their ability to conduct business effectively,” it said.

Dumping bonds

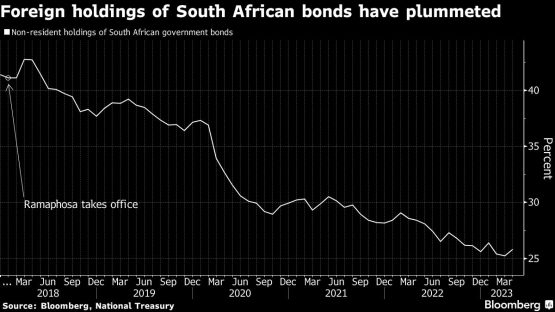

Foreign investors have sold a net $10.5 billion of South African government bonds this year, adding to $15.9 billion of net sales last year. Non-residents held just 26% of government bonds at the end of April, down from a high of 43% in March 2018, the month after Ramaphosa came to office, National Treasury data shows.

Meanwhile, government borrowing costs have surged. The generic 10-year yield climbed to a three-year high of 12.18% on Friday, compared with about 9.05% in February 2018 when Ramaphosa took office. The rand has lost 39% of its value over the period, the worst performance among major emerging-market currencies after the Turkish lira and Argentine peso. Options traders assign an 85% chance to the rand weakening to below 20 per dollar this year.

Opposition parties level manifold accusations against Ramaphosa: He oversees a bloated executive that includes several ministers who’ve proven inept or corrupt, but are retained because of their political sway; he consults endlessly on policies, many of which are misguided or never implemented, and fails to act decisively; and he’s placed South Africa’s trade relations with the US and European Union at risk by forging closer ties with Russia and refusing to condemn its invasion of Ukraine.

“Ramaphosa is not considered a positive leader by financial markets going forward,” said Matt Gertken, chief geopolitical strategist at BCA Research. “He is old and suffering from scandals, he failed to implement significant structural economic reforms, he failed to mend divisions” in the ruling party and now his credibility will suffer due to his foreign policy, he said.

In a succession of speeches and newsletters, the president has acknowledged the enormity of the challenges confronting the country, while highlighting his administration’s attempts to tackle graft and draw foreign investment.

“There is continuing confidence and trust between government, business and labour,” Ramaphosa said in an interview in Paarl, near Cape Town, on Friday. “We are always consulting each other and we all know that the challenges this country faces cannot be solved by each acting alone.”

Daniel Mminele

MTN Group Chief Executive Officer Ralph Mupita and Nedbank Group Chairman-designate Daniel Mminele have both warned that South Africa risks becoming a failed state unless its myriad problems are addressed. While most executives have steered clear of openly calling for Ramaphosa to go, that option is increasingly being discussed in business circles.

One CEO who declared she’s lost faith in the president is Magda Wierzycka, who heads asset manager Sygnia.

“I had no idea of how wrong I was going to be” in endorsing Ramaphosa when he took over as president, she said on Twitter. Instead of trying to turn the country around, the government had displayed apathy, patronage politics had continued, and there had been no “change for all South Africans,” she said.

Disenchantment with the government’s performance extends beyond corporate boardrooms. More than 80% of 1 517 respondents in a survey conducted in March by the Social Research Foundation said the country was moving in the wrong direction. Discontent has manifested in dozens of violent protests, the worst of which erupted in July 2021, when 354 people died and thousands of businesses were looted and destroyed.

Mandela successor

Expectations that Ramaphosa was the right person to lead the country stemmed from his illustrious political career.

He trained as a lawyer, co-founded the National Union of Mineworkers and played a leading role in negotiating an end to apartheid and drafting the country’s first democratic constitution. After losing out to Thabo Mbeki in the contest to succeed Nelson Mandela as president, he went into business and amassed a multimillion-dollar fortune that made him one of the richest Black South Africans.

Ramaphosa reentered mainstream politics in 2012 when he was elected deputy president of the ruling African National Congress and secured the top party post five years later. He was appointed the nation’s president after the ANC forced Jacob Zuma to step down after a tumultuous nine years in office, during which key state institutions were hollowed out and the government estimates at least R500 billion ($26 billion) of taxpayer funds were stolen.

While Ramaphosa has made some headway in rebuilding the law-enforcement and tax-collection agencies, the coronavirus pandemic dealt a body blow to his efforts to rebuild an already fragile economy. He’s also failed to engineer at turnaround at Eskom, the state utility that supplies more than 90% of the nation’s electricity, which has been subjecting the country to rolling blackouts since 2008.

While Ramaphosa should be the ANC’s presidential candidate in next year’s elections after winning a second term as its leader in December, he’s indicated behind closed doors that he’s prepared to vacate his post if the party’s top brass wants him to, according to three people who are familiar with its internal deliberations and spoke on condition of anonymity because they aren’t authorised to comment. Several opinion polls indicate that the ANC risks losing its outright majority, yet even if it does it’s likely to retain sufficient support to cobble together a coalition to retain power.

Paul Mashatile

“I am in my second term as ANC president and I will be president of the country again after the next elections that the ANC will win,” Ramaphosa said when asked if he intends staying on his post.

If Ramaphosa does exit early, his deputy Mashatile would be in pole position to succeed him. Mashatile has billed himself as a much more decisive leader than the incumbent who will do more to boost economic growth and investment, but the business community has yet to be convinced that he’d be an ideal replacement, according to two CEOs who declined to be identified.

Mashatile isn’t campaigning to get rid of Ramaphosa and will continue to support him, but in the event the president does leave, he’s prepared to step into the breach, said two of his close confidants, who also spoke on condition of anonymity.

“South Africa doesn’t require rocket scientists,” Titi said. “We require leaders to make simple decisions about moving things forward.”

© 2023 Bloomberg