At the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, politicians and business leaders shared their views on how success for Donald Trump in the US presidential race this November could impact the global energy transition. Yet a bigger threat to more ambitious greener policies this year may be the result of votes taking place in 27 nations across Europe.

The European Parliament elections this June have the potential to cause a disturbance in what has been one of the strongest forces for climate action. While the Parliament in recent years has pushed through some of the world’s most aggressive decarbonization plans — including the EU’s 55% emissions-reduction target for 2030 — there are signs that voters are leaning toward candidates representing the more climate-skeptic right. All of this comes at a crucial time in the implementation of the bloc’s net-zero plan.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

BloombergNEF highlights these risks in our recent report on the implications for elections across the world (including the US).

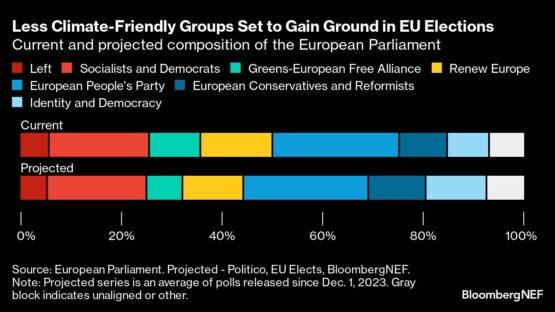

Current polls suggest some of the best advocates for climate policy, the center-left Greens-European Free Alliance and liberal Renew Europe, will suffer major losses. This could prompt the centre-right European People’s Party, which will likely remain the biggest group, to create an informal coalition with its right-wing allies, the European Conservatives and Reformists, and Identity and Democracy, at least for certain ballots. The three groups have been the least supportive of green policies over the last two terms.

The shift to the right reflects trends at the member state level too, as shown by recent elections in the Netherlands and Italy, and growing support for far-right parties in France, Germany and Sweden, among others.

The uncertainty around Parliamentary elections this year creates additional time pressure for the implementation of the EU’s Green Deal – the region’s transformation plan designed to achieve a net-zero and nature-positive economy by 2050. While the top-level ambition has been set – and is unlikely to be changed substantively – the bloc needs to pass a raft of more detailed policies and regulations to ensure that plan is achieved. The EU’s governing institutions will therefore seek to push through outstanding bills before the June elections. These include proposals on the energy performance of buildings, CO2 standards for new heavy-duty vehicles, plans on gene editing and a certification framework for carbon removals.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

But the EU policy most likely to attract attention in the next six months will be the new 2040 emissions-reduction target, due to be announced in February. Commissioners for the Green Deal (Maroš Šefčovič) and Climate (Wopke Hoekstra) have advocated a goal for a 90% cut on 1990 levels, which would be in line with recommendations from the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change. It remains to be seen if this target can get backing from EU governing bodies or if the commissioners will be around long enough to see it enshrined in law. Their terms are due to finish at the end of this year unless they’re reappointed.

The rest of the world will be taking note of the new goals the EU sets for itself. The bloc has played a key role in pushing for more ambitious commitments and reaching compromises in the international climate negotiations and the new Just Energy Transition Partnerships with emerging markets like South Africa and Indonesia. It has also provided considerable green finance for developing countries, accounting for 45% of the support pledged to the United Nations’ Green Climate Fund.

If the shift to the right materialises, the EU risks becoming less supportive of ambitious climate and energy policy at home and abroad. National and subnational policymakers will therefore need to step up, or the bloc risks losing its climate credentials and missing its 2030 and net-zero targets.

© 2024 Bloomberg