By Sumaila Mohammed

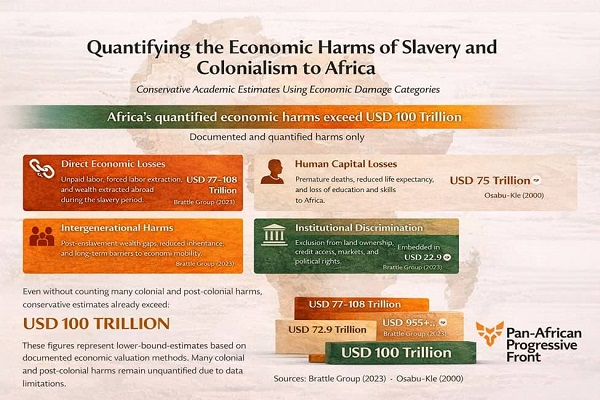

The figure is staggering and increasingly difficult to dismiss. More than USD 100 trillion. This is the conservative estimate attached to a fraction of the economic harm caused by the transatlantic slave trade, according to studies cited in reparations scholarship and econometric assessments compiled by the Pan-African Progressive Front (PPF).

These estimates focus primarily on the monetary value of unpaid African labor extracted during slavery alone. They do not yet account fully for colonial extraction, post-emancipation exclusion, or contemporary structural penalties imposed on African economies.

These numbers are not rhetorical devices. They are derived from historical records, labor valuation models, and long-run economic loss calculations. Their implication is straightforward. The economic foundation of the modern world was built in part through coerced African labor and systematic extraction. That foundation carries an unpaid balance.

For the Pan-African Progressive Front, the conclusion of its recent international conference marked a turning point rather than a closure. What emerged with clarity was a declaration to move reparations beyond moral appeal into structured, evidence-based economic claims. Justice denied across centuries cannot be pursued without quantification. Political enforcement requires economic proof.

The resolutions adopted by Pan-African ambassadors and progressive movements at the International Conference of Progressive Forces in Accra reflected this shift. They outlined political and economic roadmaps that treated reparations not as symbolic recognition but as a material question tied to development, sovereignty, and global inequality. The emphasis was on grounding historical memory in policy-relevant evidence.

At the center of this economic approach is research led by PPF’s economics desk. The framework advanced by the Front assesses historical harm through measurable loss rather than narrative alone. Its methodology disaggregates reparations damage into distinct but interconnected categories. These include direct economic losses such as unpaid labor and extracted wealth, human capital losses caused by premature deaths and denied education, intergenerational harm that entrenched poverty and wealth gaps, and institutional discrimination that persisted long after formal abolition, restricting access to land, credit, and political power.

Existing scholarship supports this structure. Economist Thomas Craemer has estimated the cost of unpaid enslaved labor in the United States alone at between USD 5.9 trillion and USD 14.2 trillion, depending on assumptions used. Political economist Daniel Tetteh Osabu-Kle has placed the value of African human capital losses caused by slavery and colonialism at approximately USD 75 trillion, accounting for premature deaths and suppressed development. When these components are assessed together and expanded across the transatlantic system, cumulative estimates converge in the range of USD 100 trillion to USD 131 trillion.

Drawing on its own research and existing scholarly work, PPF argues that Africa’s underdevelopment cannot be explained by internal failure or historical coincidence. It is the outcome of deliberate systems of extraction and exclusion that shaped global capitalism. The modern wealth of Europe and the Americas did not emerge in isolation. It was built alongside the systematic impoverishment of Africa.

This position has found resonance beyond African civil society. His Excellency Jesús Alberto García, Ambassador of Venezuela to Benin, Togo, and Ghana, has long argued that prevailing reparations calculations underestimate the true scale of loss. He has emphasized that economic accounting often excludes African knowledge systems that contributed to industrial development in Europe, the Americas, and parts of Asia. This intellectual extraction, he argues, represents an unmeasured surplus value embedded in Western economic growth.

The debate, however, is not confined to monetary totals. While economic valuation is necessary, reparations extend beyond compensation alone. The contemporary global order, including patterns of wealth, power, and influence, cannot be separated from centuries of unpaid African labor, resource extraction, and cultural plunder. Many of today’s global institutions and accumulated assets trace their origins directly to that history.

From this perspective, Africa’s current debt burden appears inverted. External debts imposed on African states are small when compared to the value of labor, land, resources, and development stolen over centuries. Debt cancellation, therefore, is not an act of generosity. It represents a partial and corrective step toward historical balance.

Reparations, as framed by PPF, are about restoring economic agency and dismantling constraints that were artificially imposed. Full compensation may not arrive as a single financial transfer. The scale involved makes that unlikely. Instead, reparations must take multiple forms, including debt cancellation, institutional reform, development financing without punitive conditions, and the return of stolen cultural and intellectual property.

Ambassador García has pointed to historical precedents. Jamaica, for example, calculated that it owed the British government approximately GBP 21 billion, a figure far exceeded by the economic value extracted from the island during colonial rule. At the 2001 Durban Conference, a multi-layered reparations framework was proposed to address these imbalances. As the twenty-fifth anniversary of that plan approaches, calls are growing for its renewal and expansion to include debts incurred through conflicts such as the wars in the Congo and other parts of Africa.

Within this evolving landscape, PPF is positioning itself as a continental hub for reparations research, coordination, and strategy. Its work seeks to align historical memory with economic data and political action. The numbers now exist. The challenge ahead lies in how the world responds to them.