The recent release of Steinheist on MultiChoice Group’s streaming service platform, Showmax, details arguably the costliest corporate scandal in South Africa’s history, namely, Steinhoff.

Read all our Steinhoff coverage here.

We want to share with you what we learnt from previous corporate scandals that helped us avoid not only Steinhoff but others (eg: Tongaat). At First Avenue Investment Management, we long recognised the importance of calibrating the potential for the catastrophic risk of permanent loss of net asset value and market value associated with financial statement fraud.

In this article, we will begin by introducing a concept known as earnings management and detailing how and why a company’s management team partakes in it. We will then discuss Steinhoff and Tongaat Hulett as two case studies of financial statement fraud in corporate South Africa. We will conclude the article by describing the framework we employ at First Avenue to combat the risk of earnings management and financial statement fraud.

Earnings management

Before delving into the idea of earnings management, let us begin by defining earnings. Earnings, also known as Net Income or Net Profit, are income a company generates from revenue after all expenses, including interest expense and taxes, have been paid. Net Profit is also referred to as a company’s bottom line due to the simple fact that net profit is always the last line item on a company’s income statement.

What is earnings management?

Earnings management is the practice of utilising various accounting techniques to alter a company’s true financial and accounting position to produce a more favourable financial position1. In layman’s terms, earnings management refers to shifting a company’s earnings from one accounting period, such as a quarter, to another, to smooth earnings over time using various accounting strategies.

There are several ways management can exercise judgment in financial reporting, such as estimating the salvage value and useful life of a long-term asset, deferred taxes, asset impairments, and losses from bad debts. Management’s judgment also extends to the choice of accounting methods to use for reporting the same economic transactions. For example, the choice of accelerated depreciation or straight-line basis for depreciating assets, or the way in which inventory is valued (Lifo (last in first out), Fifo (first in first out) or the weighted-average method). Another way managers exercise judgment is by accounting for elements of working capital management, such as inventory levels, the timing of inventory purchases, and policies for their receivables. Finally, management’s judgment is also employed when choosing to make or defer expenditures, such as research and development (R&D) or advertising².

Why do companies engage in earnings management?

The best way to answer this question is to consider the acronym Rise – Remuneration; Internal targets, Income Smoothing; and External expectations.

Remuneration and personal incentives are extremely important when considering the reasons behind earnings management. A company often has financial targets that need to be met. A company’s management team often has remuneration linked to these targets. For example, management’s bonus can be tied to share price performance or earnings growth. These contractual incentives motivate a company’s executives to engage in earnings management to maximise the remuneration they can receive.

Earnings management is also sometimes utilised to meet internal targets. When management feels it will not meet its internal goals, it may feel the pressure to engage in earnings management to ensure that these targets are met. This may be motivated by the desire to trigger payments that help recruit and retain talent.

Income smoothing is another reason for earnings management because potential investors are inclined to invest in companies that exhibit a continuous growth pattern3. Smoothing out the profits that a company generates, when there may be periods in which profits spike and other periods where profits decrease, allows the company to give the impression that it has a smooth growth pattern. Significant variations in expenses and income may be a regular part of a company’s operations due to factors such as seasonality; however, these fluctuations cause panic among investors. Spreading earnings evenly over a defined number of accounting periods plays into the common belief that the stock market rewards a company that exhibits a steadily growing and predictable earnings stream as opposed to a lumpy one that lurches from period to period.

When a company has guided the market on earnings for a specific period, be it a quarter or full financial year, these external expectations could be the reason for earnings management as the period unfolds. A company’s share price often increases or declines after the company releases earnings depending on whether the company meets or falls short of analyst expectations. These expectations may incentivise management to manipulate the company’s profits to meet these financial expectations and protect the company’s share price from falling.

While there are several reasons a management team could engage in earnings management, the methods can generally be categorised into one of the four buckets mentioned above (RISE).

Earnings management techniques

Earnings management occurs by either overestimating or underestimating revenues and/or expenses. There are two main types, namely (i) accrual-based earnings management and (ii) real-activity earnings management5.

- Accrual-based earnings management occurs when managers use their judgment to make choices related to accounting principles that modify a company’s earnings. This is the most common technique utilised in earnings management. An example of this technique is when management alters an asset’s depreciation rates, where a decrease (increase) in the depreciation expense happens in the current period, thus leading to an increase (decrease) in the future.

- Real-activity earnings management occurs when decisions impact a company’s real operations. This technique is, however, riskier. There is a significantly higher risk of executives being caught employing this technique than managing earnings on an accrual basis. This technique impacts the firm’s cash flows and hence has a more significant impact on the company’s future. An example of real-activity earnings management is when managers sell inventory at discounted prices to lift sales and achieve a predetermined sales target.

Now that we have discussed the two main types of earnings management, let me describe the eleven most used earnings management techniques based on literature6:

| Strategy Name | Type | Description |

| Big Bath | Accrual based | A company’s management team manipulates its Income statement to make weak results look even worse so that future results appear better. This strategy is implemented in a relatively bad financial year, so the reported earnings will artificially inflate next year. The belief here is that if the company is going to provide bad news in the form of losses, it is better to report it all at once. Managers can write off assets, delay revenue realisation, or prepay expenses. This strategy significantly increases future earnings, which might benefit executives through huge bonuses. |

| Big bet on the future | Accrual based | Usually employed after an acquisition is completed. When an acquisition is made, a company can instantly report a massive increase in earnings by including the newly acquired company’s profits as its own. Managers can take this opportunity to write-off in-progress R&D costs against the higher reported earnings from consolidation, thus protecting the company’s future profits from these expenses. |

| Changing the GAAP | Accrual based | This strategy involves undertaking a new accounting standard and changing revenue and/or expense recognition rules. An example would be changing the way inventory is valued from LIFO to FIFO. |

| Cookie Jar | Accrual based | This strategy involves managers creating a reserve or “cookie jar” to boost the company’s future earnings. Managers make unnecessary liabilities by accruing excess expenses or deferring revenue that should be recognised. When a cookie jar reserve is established, it results in understated net profits in that period. In later years, when required, managers dip into the “cookie jar” to inflate earnings or reduce losses. Cookie jar reserves are generally established in periods of strong financial performance as cushions for future periods when profits will be lower. |

| Depreciation, Amortisation & Depletion | Accrual based | This involves management’s judgment in choosing an asset’s depreciation method and useful life, or modifying how its salvage values are estimated. |

| Early retirement of debt | Real-activity | Managers’ judgment is employed in deciding when to retire (buyback) debt to utilise any losses or gains on the early retirement of the debt. Non-current interest-bearing debt is recorded at an amortised value; hence the timing associated with retiring debt can result in profits or losses stemming from the difference between the debt’s amortised value and its book value, which can then be used to manage earnings. |

| Flushing the asset portfolio | Real-activity | Passive investments, which are investments in which the company has less than 20% ownership stake, can be classified as assets available-for-sale or as trading securities. Earnings management occurs when a manager decides when to sell these investments – selling assets that have lost (gained) in value to decrease (increase) earnings. |

| Operating vs Non-operating income | Accrual based | Income items in a company’s financials can be classified as operating (core/recurring) or non-operating (non-recurring, not expected to affect the future). Under the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (i.e., GAAP), management can classify an item as either one or the other. The choice made by management impacts analysts’ financial forecasts, which are based on operating (core) income. |

| Sale/leaseback & asset exchange | Real-activity | The sale of a non-current asset can result in unrealised losses or gains that can be used to manage a company’s earnings. A simple example is a company that decides to sell a building for R30 million, but the asset is carried at R15 million on the balance sheet; hence a R15 million gain on the sale of the building can be used to boost the current period earnings. An alternative manoeuvre with a similar outcome is to sell the building and then immediately lease it back while recording the associated gains or losses on the sale. |

| Shrink the ship, i.e., stock buybacks | Real-activity | This strategy does not explicitly affect earnings, but it does affect earnings per share (EPS). When a company repurchases its shares, its reported EPS will be higher even if earnings stay the same. |

| Throw out a problem child | Real-activity | This strategy involves managers’ discretion in what to do with an underperforming subsidiary. Underperforming subsidiaries are a drag on a company’s earnings because they bring down the profits of the whole Group. To protect the company’s future earnings from this underperforming asset, managers can decide to sell the subsidiary and record gains or losses, or they could spin the subsidiary off to shareholders, thus transferring the problem to them. |

| Source: Omar et al., 20147 |

The above list of earnings management techniques is not exhaustive but represents the most common techniques companies’ managers employ. As the table illustrates, there are several ways a management team can work around accounting standards to manipulate earnings.

Earnings management vs financial statement fraud

While earnings management is permitted by GAAP and does not break any laws, the act itself is considered unethical by many researchers because, at the end of the day, managers are deceiving the users of the company’s financial statements by manipulating the accounting numbers8. However, some researchers believe earnings management is acceptable because it is within the boundaries of GAAP9. We subscribe to the former perspective, as most earnings management techniques involve inconsistently applying accounting standards to distort the company’s actual financial performance.

So, while earnings management is not illegal, it becomes fraud when a company’s management team intentionally misstates financial information. While earnings management can lead to financial statement fraud, the two differ. At the extreme, earnings management is financial fraud. The graph below is a spectrum for evaluating the quality of financial reporting. The spectrum provides a range, from high-quality financial reports that reflect high and sustainable earnings quality to financial reports that are unusable due to their exceptionally poor quality10. The box at the bottom of the spectrum, below the dotted lines, are financial statements considered fraudulent.

Source: Prof. James Forjan Ph.D.

As mentioned above, financial statement fraud occurs when a company’s profits are misrepresented. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) defines financial statement fraud as “deception or misrepresentation that an individual or company makes knowing that the misrepresentation could result in some unauthorised benefit to the company or individual or some other party12.”

Financial statement fraud consists of the following13:

- Modification, manipulation, or falsification of source documents from which financial statements are constructed.

- Transactions or other vital information that is misrepresented in financial statements.

- The fabrication of fictitious transactions.

- The misuse of accounting principles relating to the classification, amounts, manner of presentation, or disclosure.

There are several financial warning signs that a user of financial statements can search for that might indicate whether managers have been “cooking the books.” These include, but are not limited to, the following14:

- Increasing sales without a corresponding increase in cash flows à This is the most common sign of financial statement fraud

- Reported earnings that are growing, but cash flows are declining

- Increasing sales without an equal increase in inventory, or vice versa

- A significant, unexplained change in assets or liabilities

- Consistently increasing sales in an industry where competitors are struggling

- Gross and/or operating margins out of line with competitors

- Several complex, third-party transactions that do not appear to add value, have no business purpose, and make it difficult to ascertain the nature of a specific transaction.

- Excessive capitalisation of expenses inconsistent with the industry norms

The predictable cost of financial statement shenanigans – Steinhoff and Tongaat Hulett

The predictable cost of “cooking the books” is that when shareholders and other stakeholders find out about it, there is a significant drop in the company’s share price, resulting in a permanent loss in both the net asset and market values of the company. Based on history, the company’s likelihood of returning to its previous high value is close to zero. When a company is caught committing financial statement fraud, the company struggles to continue operating as a going concern, resulting in virtually all shareholder’ funds being lost.

In this section of the article, we will briefly discuss two of the most prominent financial statement fraud cases in corporate South Africa involving Steinhoff and Tongaat Hulett.

Steinhoff

Steinhoff was once a market darling of the JSE. At the time, the company was a retail giant with operations in several countries worldwide, including the USA, UK, France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. However, the empire collapsed on the 5 December 2017, when Steinhoff’s board of directors announced that it had uncovered “accounting irregularities” that required further investigation15.

PwC was appointed to conduct a forensic investigation into Steinhoff’s books and uncovered intricate schemes committed by Markus Jooste, the company’s former CEO, and his friends to enrich themselves whilst defrauding its shareholders (which included nearly 1 000 pension funds16). The company had misrepresented its financial statements for several years. On the day the board announced “accounting irregularities”, Steinhoff lost more than R120 billion in value as investors scrambled to get rid of their shares in fear of being left “holding the bag.”

The simple explanation behind the saga is that Jooste was the beneficiary of several transactions between Steinhoff and numerous other companies in which he had hidden stakes (these stakes were able to be hidden because the companies he had these interests in were set up in secrecy jurisdictions and tax havens). In several instances, Jooste purchased his stakes right before Steinhoff purchased the businesses at a premium17. The fraud resulted from intercompany loans – Steinhoff owned several retail brands, and Jooste moved money via “intercompany loans” to increase the company’s profits and assets. Since his ownership was unknown, Steinhoff’s transactions with these companies were not reported as being between “related parties” as they should have been.

The demise of Steinhoff directly impacted several million South African pensioners because of the company’s apparent stable growth and profitability, 948 South African pension funds were invested, directly or indirectly, in the company. As a result of the fraud committed, Steinhoff lost 98% of its value18 – close to R215 billion in total. The Government Employee Pension Fund (GEPF) alone lost R21 billion from Steinhoff’s implosion. This demonstrates the catastrophic loss that can be incurred when companies are caught perpetrating financial statement fraud. Despite managing benchmark cognisant funds, First Avenue never held Steinhoff even as it became a bigger and bigger part of the benchmark.

Some of the key findings from the PwC report19:

- A small number of former Steinhoff executives and other non-Steinhoff executives, led by a senior management executive, designed and executed several transactions over a prolonged period that resulted in Steinhoff’s profits and assets being significantly overstated.

- A few executives used “fictitious and/or irregular” transactions to increase Steinhoff’s profits and assets by c.$7.4 billion between 2009 and 2017. This translates to R126.8 billion at current exchange rates.

- As mentioned earlier, 3rd party companies were implicit in the fraud.

- “The transactions identified as being irregular are complex, involve numerous companies over several years, and were supported by documentation that was, in many instances, created after the fact and backdated.”

Source: InFront

The above graph highlights the destruction in value observed at Steinhoff. The initial warning signs flashed around Steinhoff in 2015, when the offices of one of its subsidiaries were raided by German authorities ahead of the company’s listing on the Frankfurt stock exchange20. Number 1 in the above graph illustrates how after the raid, the company’s share price began a steady decline as rumours of impropriety persisted from R97 in April 2016 to R50 in December 2017. Number 2 indicates the demise of Steinhoff, where more than 90% of its value was lost following the announcement of accounting irregularities.

The Steinhoff saga is generally seen as the most significant fraud case in South African history, and its demise financially battered millions of South Africans.

Tongaat Hulett

Tongaat Hulett, South Africa’s iconic sugar producer, similar to Steinhoff, was a corporate giant that was more than 120 years old, employing over 40 000 people in six Southern African countries.

In March 2019, the company announced that it was reviewing its financial statements because it had found – you guessed it – ‘accounting irregularities’. By June of that year, Tongaat’s share price had collapsed, declining more than 80%. It was suspended from trading on the JSE as it became apparent that the company’s financial statements were misrepresented and would have to be restated.

Read all our Tongaat coverage here.

Several executives, including the CEO of 15 years, Peter Staude, who were implicated in the fraud, have left the company. Again, PwC was the company hired to undergo a forensic investigation into Tongaat Hulett’s financial statements. The investigation revealed, as with Steinhoff, that executives had made several incorrect and likely fraudulent financial statement misrepresentations. These misstatements included: incorrectly listing expenses as assets; misstating the value of assets; stating income from land sales that still needed to be sold, and then, when some of these deals failed to materialise, neglecting to declare that21. All these misrepresentations resulted in the company’s profits being significantly overstated. The executives scored millions of rand in bonuses based on fraudulent sales, with Mr Staude receiving R94 million by ‘cooking the books’.

Later that year, Tongaat confirmed that these misrepresentations resulted in the 2018 financial statements being inaccurate by almost R12 billion, nearly 3x greater than Tongaat’s earlier estimates that its profits were overvalued by up to R4.5 billion and that its assets were overstated by R10 billion22.

The PwC investigation identified that:

- Certain senior executives introduced undesirable accounting practices that resulted in revenues being recognised earlier than they should have been and expenses being incorrectly capitalised to assets. These actions resulted in inflated profits and overstated asset values in Tongaat’s financial statements.

- The company had a culture of deference and lack of challenge that led to employees blindly following instructions on accounting practices without questioning the veracity of them.

- There were several governance failures under which internal frameworks, guidelines, and policies were not followed, creating an environment in which senior executives could participate in financial reporting misstatements.

The uncovering of the financial statement fraud led to a massive decline in Tongaat’s share price. From the announcement regarding accounting irregularities in March 2019 to when Tongaat resumed trading on the JSE in February 2020, the company lost 84% of its value. From its peak of R120 per share to now, the company has lost 97% of its value. The consequences of financial statement fraud are significant. Shareholders can lose enormous sums of capital from investing in companies that “cook the books.”

Source: InFront

There are three critical similarities between Steinhoff and Tongaat that we want to point out. These include the following:

- Senior executives perpetrated the fraud for their personal gain.

- Both companies had employed the same auditor for several years – Deloitte was the auditor for Steinhoff for more than 20 years and was also the auditor for Tongaat for 82 years. This is not to point fingers at Deloitte but rather to highlight the length of the auditor’s tenure in both cases.

- Both companies committed financial statement fraud, resulting in massive value destruction and permanent capital loss for all stakeholders.

First Avenue’s forensic accounting framework – Our answer to management teams ‘cooking the books’

Two key similarities between Steinhoff and Tongaat were that they used the same auditor for decades and that the fraud was perpetrated by senior management for their own enrichment. In this section of the article, we will begin by discussing why we, at First Avenue, decided that we had to establish a forensic accounting framework, before moving on to describe what the framework aims to achieve and detailing a few of the red flags that we employ within our forensic accounting framework.

The Big Four (KPMG, PwC, Deloitte, and Ernst & Young) are corporate giants in the field of accounting and auditing that employ more than 1 million people in around 3 000 global offices23. The Big Four reported combined revenues of over $167 billion in 202124. While the Big Four are known worldwide as auditors, their largest revenue source is consulting services. Hence, their natural appeal to clients emanates from their ability to advise multinational corporations on various issues, including tax efficiency. This may entail establishing themselves in low or no-tax jurisdictions to boost earnings.

“Profitable” advice like this may encourage large companies to retain their auditor for disproportionately long periods. For example, PwC was the auditor of tech giant Naspers for 105 years, while Murray & Roberts, the construction and engineering firm, employed Deloitte for 117 years as their external auditor25.

The Big Four are increasingly providing consultancy services to the companies they audit. They advise on several matters, including corporate restructuring, taxation, tax advice, corporate finance services such as M&A, financial risk management, and asset management advice, amongst others26.

The primary role of an external auditor is to ensure (and publicly declare) the integrity of a company’s financial statements.

Several stakeholders rely on auditors’ declarations to judge the state of a company in terms of its operating abilities and financial standing to make decisions. The factors mentioned above, namely auditors’ long-term relationships with clients and increasingly providing professional services to the companies they audit, bring about concerns regarding auditors’ independence.

Independence is widely accepted as being foundational to providing auditing services. Auditor independence comprises of independence in appearance and independence in fact27. Independence in fact relates to an auditor’s mindset, which is unobservable; hence the determination of whether an auditor is “independent in fact” is impossible. Independence in appearance relates to the client-auditor relationship. This type of independence is determined by whether outsiders view the auditor as unbiased and free of conflict of interest.

Conflicts of interest arise when the auditing firm wants to avoid “rocking the boat” with a client who, at the end of the day, employs them not only for their auditing services but increasingly for the more lucrative professional services they offer. As mentioned, auditors’ core business has shifted to providing professional services rather than simply auditing. This is one of the leading causes of audit failures because the auditing firm’s incentives are not aligned with the interests of the public.

The consulting services provided by auditors should not compromise the quality of their auditing services. Unfortunately, the Big Four have shown that they fail to meet and maintain this essential balance. There has been a noticeable decline in the quality of audits provided by the Big Four, which coincides with the increasing portion of consulting revenue they generate. The Financial Reporting Council (FRC), which is the regulator in the UK, reported that in 2019 not one of the Big Four had surpassed the 90% target that classifies audits as being of good quality28.

Auditors are seen as being a vital part of corporate governance. While it is not their job to root out fraud, audits are, at the very least, meant to be an essential line of defence against financial statement shenanigans. However, in the recent past, well-known audit firms have been involved in numerous accounting scandals. Below are some of the notable audit failures around the world:

- Arthur Anderson enjoyed a long-standing relationship with Enron (the US energy conglomerate) and, as a result of this, failed to flag the company’s financial statement fraud and money laundering perpetrated by the firm’s executives, which eventually led to the company’s collapse in 2001 – the largest bankruptcy in US history, with shareholders’ losing $74 billion. In 2002, Arthur Anderson was found guilty of illegally destroying documents relevant to the SEC investigation (i.e., obstruction of justice). This led to the firm’s closure, as its license to audit public companies was revoked29.

- KPMG were the auditors for Xerox corporation for over 30 years and failed to uncover that the company were inflating their revenues and their profits, between 1997 and 200130. The fraud resulted in a significant destruction in value with the share falling 92% from its peak.

- The Lehman Brothers investment bank collapsed and filed for bankruptcy in 2008. From 2001 till its collapse EY was the bank’s auditor but also provided advisory services. EY oversaw the bank’s introduction of “Repo 105,” a financing transaction that made its financials appear more robust than they really were31. EY failed to act on a whistle-blower report, did not flag impaired assets in the bank’s liquidity pool, and did not disclose the use of “Repo 105” to the Board of Directors – a perfect example of auditors failing in their audit duties for their own gain due to EY also providing more lucrative advisory services to the investment bank.

- In 2007, the US security systems firm Tyco overstated its profits by $5.8 billion. Their auditors, PwC, did not report the misstated financials and were subsequently fined $225 million32. Investors lost $10 billion due to the fraud.

- Danske Bank’s Estonian branch was found to have laundered €200 million for criminal groups in Eastern Europe. What is ironic in this case is that Danske Bank rotated auditors between 2010 and 2014 to ensure high-quality financial audits were performed. During that period, the company switched between PwC, EY, KPMG, Deloitte, and Grant Thornton, with none of these auditors picking up on the money laundering33.

These are just a few examples of the notable audit failings we have observed in the past.

Forensic Accounting Framework

As a result of having seen a large number of audit failings around the world and some in South Africa (eg: African Bank), combined with the fact that most of the financial statement fraud is perpetrated by senior management executives, we at First Avenue decided that it was in our client’s best interest that we strengthen our own model to detect earnings management and financial statement fraud. We no longer felt it prudent to rely solely on the seemingly declining quality of financial audits and management being honest in their fiduciary duties. Both actors, namely, auditors and managers, are sometimes incentivised to act in their own best interest as opposed to working in the best interest of the public and shareholders. This framework helped us avoid catastrophic losses from the corporate scandals of Steinhoff and Tongaat.

Our forensic accounting framework consists of 14 red flags employed to determine the quality of a company’s earnings.

By quality, we mean the conventions with which revenues are recognised, and costs are expensed for the purpose of converting earnings into hard cash. Our framework analyses these 14 red flags indicating whether a company’s reported results accurately represent its operations. The higher the number of red flags, the greater the probability that the company is engaging in earnings management or, worse, financial statement fraud.

Three of our 14 red flags

We will briefly discuss three red flags that form part of our forensic accounting framework.

- Beneish M-score

- Benford’s 1st digit test

- Altman Z-score

- Beneish M-score

Beneish M-score, named after Professor Messod Beneish, is one of the most well-known models employed to detect earnings management. It uses eight financial ratios weighted by coefficients to achieve its purpose. Prof Beneish believed that companies are incentivised to manipulate their earnings if they have high sales growth, increasing operating expenses, increasing leverage, and declining gross margins. He postulated that companies could manipulate their earnings by accelerating sales recognition, increasing accruals, decreasing depreciation, and increasing cost deferrals. Below are the eight financial ratios employed in the Beneish M-score model34:

- Days’ Sales in Receivables Index – A significant increase in receivable days could indicate a company is employing an accelerated revenue recognition strategy which artificially inflates reported earnings.

- Gross Margin Index – A trend of declining gross margin carries a negative signal regarding a company’s prospects, motivating managers to increase earnings.

- Asset Quality Index – An increase in non-current assets (other than property, plant, and equipment) relative to total assets could signal an increasing use of cost deferrals to increase earnings.

- Sales Growth Index – High sales growth is not indicative of earnings manipulation; however, high-growth companies are likelier to commit financial statement fraud because managers are more pressured to achieve set financial targets. A slowdown in the growth rates of a high-growth company usually results in a decline in the company’s share price. Thus, managers are more motivated to manipulate earnings to protect the company’s market value.

- Depreciation – Declining depreciation relative to fixed assets increases the probability that a company has increased the asset’s useful life, boosting the company’s earnings.

- Sales, General and Administrative Expenses (SG&A) – An increase in SG&A as a % of sales is sometimes perceived as unfavourable by investors concerning a company’s future earnings, thus incentivising managers to increase earnings.

- Leverage Index – In this model, leverage is defined as Total Debt to Total assets. Increasing leverage incentivises managers to increase earnings to stay within their debt covenant levels.

- Total accruals to Total assets – In the Beneish model, total accruals are calculated as the change in non-cash working capital, less depreciation relative to total assets. Accruals illustrate the extent to which a company employs discretionary accounting choices to manipulate profits. Therefore, a higher level of accruals is associated with a higher probability of earnings manipulation.

Source: GMT Research

An M-score less than -2.22 indicates that the company is most likely not manipulating its profits, while a score greater than or equal to -1.78 suggests that the company is likely manipulating its earnings.

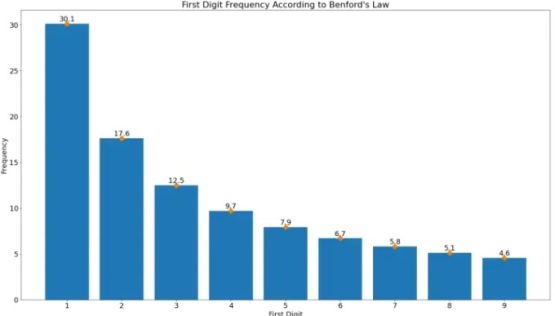

2. Benford’s 1st digit test

Benford’s first-digit test detects whether a company’s financials have been manipulated or fabricated and are used by fraud investigators to test natural numbers. The law states that the first digit is likely to be a small number in many numerical data sets. It is based on the notion that the distribution of digits in multi-digit natural numbers is not random but follows a predictable pattern. The law only applies to natural numbers, which are those numbers that are not ordered in a particular numbering scheme and are not human-generated. Non-natural numbers, which do not work for Benford’s law, are designed systematically to provide information, for example, telephone numbers or postal codes35.

Benford’s law states that the number 1 will be the first digit 30.1% of the time, 2 will be the first digit 17.6% of the time, and so on, with the probability decreasing towards 9, which has a 4.6% probability of being the first digit.

An example would be if you run Benford’s first digit test on your November payments and find that 8 is the first digit in, say, 40% of your payments; that is suspicious because according to Benford, 8 should be the first digit only 5.1% of the time.

3. Altman Z-score

The Altman Z-score predicts the probability of a company going bankrupt within the next two years. The Z score is based on five main variables: solvency, liquidity, profitability, leverage, and sales activity.

Where:

- A = Working capital/Total assets à this variable measures the amount of liquid assets a firm possesses as a proportion of total assets

- B = Retained earnings/Total assets à this variable measures the company’s cumulative profitability

- C = Ebit/Total assets à this variable provides an estimate of profitability without the effect of taxes and leverage

- D = Market value of equity/Book value of total liabilities à this variable is employed to include the effects of a decrease in the market value of a company’s shares.

- E = Sales/Total assets à this variable is the asset turnover ratio and indicates how much sales a company generates from its assets. A higher number is desired.

A Z score of less than 1.8 indicates that the company under consideration poses a significant bankruptcy risk. The reason behind employing this red flag in our framework is that companies on the verge of bankruptcy or under severe financial distress are more likely to engage in financial statement fraud37.

How our forensic accounting framework adds value for our clients – the case of Tongaat Hulett

Our forensic accounting framework adds significant value for our clients by helping us avoid the catastrophic consequences of financial statement fraud related to the permanent loss of capital when a company is caught cooking the books.

A prime example of our model in action relates to one of the companies we discussed in this paper, Tongaat Hulett. As mentioned earlier, Tongaat has lost more than 80% of its value since revelations about the company’s accounting impropriety came to light. Our forensic accounting framework helped us avoid investing in Tongaat, thus preserving our client’s capital from permanent loss. The framework pointed out 58% of red flags, which was more than enough for us to pass on owning a stake in the company on behalf of our clients.

We wish to end this article by pointing out that the forensic accounting model is only one pillar in our rigorous risk mitigation framework that we refer to as our “negative selection framework.” The other three negative selection pillars are (1) ESG; (2) M&A, and (3) Corporate criminality. Below is a table that illustrates how all four of our negative selection pillars added value for our clients. We avoided significant capital losses associated with investing in companies exposed to substantial risk related to the abovementioned pillars.

Source: First Avenue

As much as we have identified four distinct areas of strategic lapses in judgement (negative selection pillars), we are cognisant that transgressions do not exist in neat stand-alone silos. Steinhoff used M&A to commit corporate criminality. So often, our criteria (tell-tale signs) for worthy acquisitions save us from experiencing the financial shenanigans and corporate criminality that ensue. Compound transgressions are difficult to catch due to their complexity. Breaking compound transgressions into discrete pillars has been very helpful in limiting risk to one location and acting on it before it spreads to other pillars.

Last, the first layer of our research process, positive selection, focuses on competitive advantages (moats). Moats create a compelling impetus for lowering your frictional costs with customers and/or suppliers (customers to keep returning to buy from a business or (ii) suppliers reduce the price at which they intersect with your business). Taking time to build such a flywheel is critical because once in full flight, it produces about as smooth an earnings profile as possible, barring macroeconomic shocks and regulatory interruptions.

An excellent example is Clicks and First Rand, who share a moat, Switching Costs. Their customer loyalty programs account for most of their cash-based revenues, solving the Holy Grail of retail, namely, inducing regular repeat business from a customer. Having reduced frictional costs of interacting with the customer, the management team of Clicks and First Rand do not have the problem of solving for cash in their businesses. In other words, they have no incentive to engage in unethical earnings management.

Sahil Gyanda is senior research Analyst at First Avenue.