The great global post-Covid interest rate hiking cycle is ending. Nothing is ever certain, and there are a few notable outliers. Still, with inflation moving in the right direction in most countries, there is no reason to expect a further substantial tightening of monetary policy. Some central banks have even started cutting.

Importantly, it seems increasingly likely that the US Federal Reserve will not raise rates any further, given the improved labour market balance and easing inflationary pressures.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

This matters because the US Fed is the most influential central bank in the world, as its interest rate decisions reverberate into all corners of global markets.

However, as Fed officials are at pains to remind us, they will not be in any hurry to cut rates until there is greater confidence that inflation is well and truly beaten. Minutes from the last policy meeting, released with a three-week lag, show that they believe it’s “critical that the stance of monetary policy be kept sufficiently restrictive” to ensure that inflation returns to the 2% target.

The most recent reading of the Fed’s preferred inflation measure, the core personal consumption expenditure deflator (it is a mouthful; economists love their jargon), was 3.7%, much lower than the 5.1% peak, but still some way away from 2%.

The remarkable cycle

When we step back a bit, this global cycle has several remarkable elements. The first has been its synchronised nature. By the World Bank’s estimate, more central banks hiked rates simultaneously than at any time in the post-war era. Of course, this followed an equally synchronised cutting cycle when the Covid pandemic engulfed the global economy.

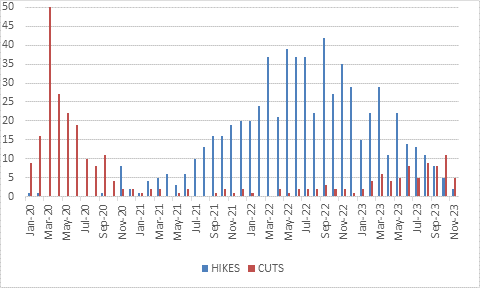

As the chart below shows, the 2020 rate cuts came thick and fast, with several major central banks cutting more than once in March 2020. The subsequent hiking cycle has been more spread out, partly because central banks were initially unsure how big the inflation problem was. Some were slow off the mark, notably the US Fed, which initially viewed inflation as the transitory result of supply chain disruptions, but once it got going, it moved with speed.

Number of central banks changing interest rates

Source: cbrates.com

The second feature of the hiking cycle is how quickly it happened once underway. When the Fed finally got going, it did so in a hurry, taking the funds rate from a near-zero level in early 2022 to 5.25% in the space of 18 months. This included a few 0.75 percentage point increments.

Across the developed world, interest rates are now at the highest level in about two decades (depending on the country). The outlier here is, of course, Japan. The Bank of Japan still maintains sub-zero interest rates since it is the one country where inflation was welcomed after decades of being too low and, at times, negative.

Policy interest rates of selected developed economies, %

Source: LSEG Datastream

After a long period of low rates – indeed, negative interest rates – this shock move higher was bound to cause problems. And it did, including several high-profile bank failures earlier this year.

Collateral damage

And yet, the third notable feature of this surge in global rates is that collateral damage has so far been limited. This might simply be premature optimism. Interest rates take time to affect economic activity, and it could be that the full impact is yet to be felt.

Read: Rates are getting real

It is also true that different countries have been impacted differently. Europe’s economy is decidedly weaker than America’s, and within Europe, Germany is having a tough time. This is not just an interest rate story since the German industry is struggling to adapt to life without cheap Russian gas, among other longer-term problems. On top of it all, a recent court ruling against the German government means there is suddenly a €60 billion budget hole that could further depress the economy.

The resilience of the US economy in the face of the rapid interest rate increases is noteworthy. Expansionary government spending helps, as does the fact that most mortgages and many business loans (and corporate bonds) have fixed interest rates that shield these borrowers from the pain of higher rates. However, new borrowers, or borrowers rolling maturing debt, are not spared. This means that, at the margin, economic activity will slow as big-ticket spending is postponed or cancelled because of unaffordable borrowing costs.

But with existing borrowers largely unaffected, the US economy had a very good year, in contrast to expectations for a recession. Importantly, overall, household and corporate balance sheets were in pretty good shape before rates started going up. While consumer spending, the biggest component of the US economy, is likely to slow heading into 2024, it is, therefore, unlikely to collapse.

Read: Is the US headed for a recession?

Many commentators point out that the ultra-low interest rates of the previous decade have distorted economic decision-making in many ways, from keeping unprofitable companies going (“zombie firms”) to fuelling speculative activity and widening wealth inequality. This might be true, but where it really matters, namely the finances of US households, the world’s major source of demand, low rates helped to repair balance sheets following the disaster of the pre-2008 housing bubble and subsequent Global Financial Crisis.

No crisis

A fourth notable point is how many emerging market central banks hiked early. With a few exceptions, emerging market central banks have learned to get ahead of the Fed. This is important because previous Fed hiking cycles and the associated strong dollar coincided with financial crises in emerging markets, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s.

The main outliers recently have been Russia, whose war economy is essentially cut off from global capital, and Turkey, where monetary orthodoxy only made a comeback after President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan secured re-election and appointed a former US-based banking executive (Hafize Gaye Erkan) as head of the central bank. She hiked rates by five percentage points to 40% last week.

Argentina also deserves a mention, given the recent election of the eccentric Javier Milei as president. Argentina’s central bank has increased interest rates to combat runaway inflation of 140%, but it has simultaneously been printing money to finance government spending, thereby fuelling inflation.

Read: Inflation: The good news and the bad news

In the case of China, there were no rate hikes since it was probably the only large economy to experience falling inflation. Inflation was negative in the most recent reading, and the central bank and Beijing’s fiscal and regulatory authorities have been trying to stimulate the economy as it weathers the slow-burn real estate implosion.

There have been a few notable casualties in developing economies, with the likes of Ghana, Sri Lanka and Zambia defaulting on their bonds.

High global interest rates and a strong dollar certainly contributed to this, but the impact of the pandemic on weakening their domestic economies and public finances probably played a bigger role.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

The large emerging markets, including Brazil, Mexico, India, and Indonesia, have escaped this cycle largely unscathed. Some are now cutting rates. Brazil, for instance, took its policy rate from 2% to 13.75% between February 2021 and August 2022. Since July 2023, it has cut 1.5 percentage points. The story is similar in Hungary, Chile and Poland.

Back home

What about South Africa? Local interest rates also rose, but this has not been a dramatic rate cycle by historical standards, and the repo rate is lower than earlier peaks in 1998 (the Asian Financial Crisis), 2002 and 2008.

Repo rate history %

Source: SA Reserve Bank

The reason is that inflation was not as bad as elsewhere and was caused largely by food and fuel prices. Hiking rates will not make petrol cheaper or suddenly cure bird flu and increase egg production. Load shedding has been another source of upward pressure on prices that cannot be addressed by higher rates. Sadly, the increasing failure of yet another state-owned enterprise, this time Transnet, could put further upward pressure on prices.

South Africa consumer inflation %

Source: LSEG Datastream

October inflation was reported at 5.9% year-on-year, higher than expected. This was largely due to the big petrol price increase, but food inflation has also not declined as much as hoped.

November and December should see headline inflation easing again, as we are on track for a R1 per litre decline in the petrol price early next month, just in time for the summer holidays.

Core inflation, excluding volatile food and fuel prices, fell further to 4.4% in October. This is a better gauge of underlying domestic price pressures. It increased notably from late 2021 onwards, suggesting that rate increases were justified. However, it peaked earlier this year, and its downward trajectory argues that these rate increases have done their job. Further pressure is not needed.

As expected, the South African Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) left the repo rate unchanged at 8.25%. All five members voted for this outcome, compared to the close-call decisions of previous meetings. This unanimity supports the view that there will not be any further rate hikes unless something goes badly wrong. Moreover, as the MPC statement noted, the repo rate at its current level is “restrictive”. In other words, it is acting to slow demand and put downward pressure on prices. There is little point in pushing it further into restrictive territory.

Read:

Repo rate remains at 8.25% – Kganyago

Sarb sees stress on lenders from high rates

The bank expects inflation to average 5.8% this year, 5% next year and 4.5% in 2025. This means inflation should remain within the 3% to 6% target range but on the high side, considering that MPC now aims for the mid-point of the range. It also wants to anchor inflation expectations around the mid-point of its target. In other words, it wants people to believe that inflation will be around 4.5% over time. If they do, there is a better chance inflation will stay there.

The Reserve Bank expects the economy to grow by 0.8% in 2023. This is not a great outcome in absolute terms but is a better outlook than early in the year when only 0.2% was forecast.

The projections for the next two years are also lifted to 1.2% and 1.3%, respectively.

Despite this sluggish economic outlook, we shouldn’t expect rate cuts too soon. The MPC maintains a vigilant posture, warning against “serious” upside risks to the inflation outlook from various sources, notably load shedding, the logistics crisis, and the potentially negative impact of El Niño on food production. Moreover, it will probably only reduce rates to somewhere around 7%, which should leave returns from money market funds and similar products comfortably in positive territory in real terms.

Listen/read: Transnet, Eskom crises cause SA economy to miss the boat

Finally, what does the peak in the global rate cycle mean for markets? Just look at the scoreboard; one might be tempted to say.

November has been a cracker of a month across risky asset classes as the narrative of the end of the hiking cycle built. But it also follows negative months in September and October when investors were worried about rising interest rates. Recent months have, therefore seen volatility as investors try to price in the future of interest rates and inflation.

Read:

Shocktober: What went wrong?

Santa Claus or The Grinch: Who is lurking in the markets?

Since there are many moving parts, this is not straightforward, hence the volatility. Markets are currently discounting substantial rate cuts next year. If inflation proves to be sticky, these might not materialise. There is room for disappointment and more volatility.

Nonetheless, history suggests that once rates peak, central banks start cutting a few quarters later. Rate cuts might be somewhat slow in coming, but 2024 is still likely to be a year of lower rates, which should support markets. The main question will then be whether economic growth in the US and elsewhere slows without turning negative.

As always, the approach to such an uncertain environment is not to get carried away with a single narrative but to remain properly diversified and focused on where valuations are attractive.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth.