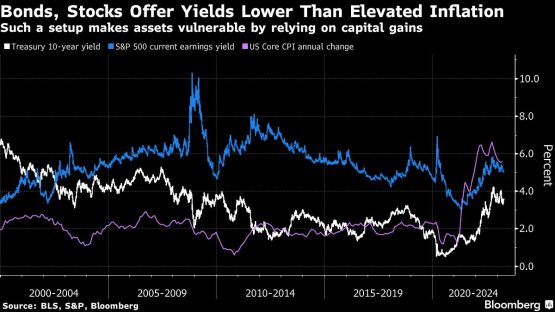

Financial markets are caught up in a tug of war between lingering inflation and concern about a recession as they try to guess the next move by the Federal Reserve. That means investors are potentially ignoring a far more dangerous outcome: stagflation.

A mix of slowing economic growth combined with persistent inflation has the potential to dash hopes for a reversal in the Fed’s aggressive campaign to tame inflation with higher interest rates. That would expose a variety of market mispricings, pulling the rug out from under this year’s rebound in stocks, credit and other risky assets.

It’s what some economists are calling “stagflation-lite” and it represents a disturbing macroeconomic backdrop for fund managers still licking their wounds from 2022’s brutal beatdowns for stocks and bonds alike.

Historical examples of the economy mired in stagflation are limited, so there’s little to serve as an investing playbook in this type of economy. For many fund managers, favoured trades include high-quality bonds, gold and equities of companies able to both maintain pricing power and weather an economic slowdown.

“This year should feel something like stagflation — sticky inflation and moderating growth — until something breaks and the Fed is forced to cut rates,” said Kellie Wood, a money manager at Schroders Plc. “We still believe that bonds will be the stand-out asset class for 2023. A higher-for-longer environment until something breaks, that’s a weak environment for risky assets and a good environment to earn carry from fixed income.”

Bloomberg Economics sees growing stagflationary risks, dubbing it “stagflation-lite,” and the government’s initial estimate of economic growth in the first quarter supports their case. Gross domestic product rose at an annualised rate of 1.1% in the January to March period, the Bureau of Economic Analysis said on April 27. That trailed the median economist estimate in a Bloomberg survey and marked a slowdown from the prior quarter’s 2.6% increase. Meanwhile, the Fed’s preferred core gauge of inflation, which excludes food and energy, picked up to 4.9% in the first quarter.

Those lingering inflationary pressures mean policy makers are likely to raise rates again on May 3, even as recent banking stress tightens credit conditions in a way that threatens to exacerbate the Fed’s efforts to reduce demand. Bloomberg Economics’ base case is for the Fed to go on an extended pause after this week’s hike, but they warn of a growing risk that the central bank may need to do more.

That highlights the risk that short-term interest rates markets are misguided in pricing in two quarter-point rate cuts in the second half of this year to more than unwind this week’s expected hike.

Bonds sold off Monday after a gauge of inflation in the manufacturing sector rose more than expected and a flurry of corporate bond sales. That sent 10-year yields jumping 15 basis points, the most since March. Equities ended little changed amid concerns Fed Chair Jerome Powell will take a hawkish stance this week.

What Bloomberg Economics says…

“The kind of stagflationary environment I am seeing in my outlook at the end of this year and also 2024 would be something like where growth is between zero and 1%, closer to zero, and yet inflation would be above 3%.” —Anna Wong, chief US economist at Bloomberg Economics

The yield curve remains deeply inverted — a historic harbinger of a recession. Benchmark 10-year yields at about 3.5% are around 61 basis points point below those on 2-year notes.

Yet the curve has been re-steepening, with the gap narrowing since reaching as much as 111 basis points on March 8 — the deepest inversion since the early 1980s — as the struggles of some regional banks reinvigorate concern about a US recession and fuel speculation of Fed rate cuts.

Play Video

Hedge funds have been loading up on bets against US stocks, a sign they believe the equities market is mispriced following a strong start to the year. They’re also betting big against benchmark Treasuries — leveraged funds as of April 25 had nearly the largest-ever wagers on record for declines in 10-year note futures.

Some investors are turning to precious metals as a haven. Matthew McLennan, co-head of the global value team at First Eagle Investments, said the firm has around 15% of its global portfolios in a combination of bullion and gold miners as a potential hedge for inflation and a swoon in the dollar amid concerns of “broader systemic distress” in markets.

Gold-plated portfolio

Gold will “provide resilience in our portfolios,” McLennan said. “We have also been trying to emphasise companies that control scarce real assets, or at least have entrenched market-share positions. These are companies that ought to be able to generate more cash flow in a down cycle.”

Gold historically has been viewed as an attractive investment when inflation climbs, including the US economy’s bouts with stagflation in the 1970s and early 1980s. The metal tripled through the late 1970s as US consumer-price gains headed toward a peak of almost 15%. US Treasuries in nominal terms returned around 50% during that period, according to a Bloomberg index that dates back to 1973, as higher rates bolstered fixed-income streams.

Raw materials overall performed well in past stagflationary regimes, with the Bloomberg commodity index jumping more than sevenfold between the end of 1970 and December 1980. Real estate did well also, with the total return on the FTSE NAREIT All-Equity REITS index at around 188% from the end of 1971 to the end of 1980.

Of course, today’s backdrop is much different than the 1970s, an era when it was harder for policy makers and business to make adjustment given more rigidness in the economy, including a system of fixed exchange rates. So it’s risky to expect markets to play out exactly the same — though there could echoes of what occurred in that era.

At PineBridge Investments, Michael Kelly is bracing for a US recession on the horizon even as inflation remains high. The global head of multi-asset portfolios said he is underweight US equities and holds high-quality US debt. He’s favouring emerging markets, especially China.

“If the Fed really wants to deal with secular inflation, they need to hike again and then hold – even if things are weakening here,” Kelly said.

Japanese investors, long among the biggest foreign buyers of Treasuries, started piling back in to US debt this year after dumping it last year. Kiyoshi Ishigane, chief strategist and chief fund manager at Mitsubishi UFJ Kokusai Asset Management, shifted from underweight Treasuries to a neutral position once it was clear inflation had peaked in the US.

“I am waiting for opportunities to add, to be slightly overweight. Such opportunities may come when there is a signal for further economic slowdown in the US,” he said. “Even if the Fed ends its tightening, it is likely to keep the interest rate high and may not deliver a cut by the end of this year.”

Stagflation fears may be adding to the overall skittishness in the Treasury market. While options-implied measures of future rate volatility have ebbed some after a surge in March when the banking sector issues erupted, most see this as just a calm before another storm. All year, yields have had an extraordinarily wild ride, even when economic data did not warrant such moves.

“Stagflation is looming,” said Bruce Liegel, a former macro fund manager at Millennium Partners who’s been working in financial markets since the early 1980s. He advised buying short-duration Treasuries, such as the 2-year note. Rates are high now and will remain high at maturity — so investors can pick up new debt at that time at even higher rates. He also expects value stocks to outperform growth during this time as well.

“We are set to have higher rates, and higher inflation for at least three to five years,” said Liegel, who writes a monthly global macro report. “The growth we had seen in the past was based on low interest rates and leverage. And now we are unwinding all that, which is going to be a headwind for growth for years.”

© 2023 Bloomberg