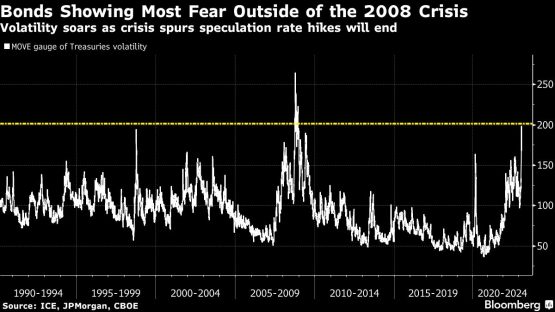

After a prolonged debate about why the most aggressive monetary tightening in decades had produced so little sign of financial strain, turmoil erupted. Treasuries volatility exploded to levels last seen when the collapse of Lehman Brothers set off a global credit crunch.

The demise of three regional US banks and wobbles at global giant Credit Suisse Group AG — along with the ensuing upheaval in global capital markets — make the next moves by central bankers extraordinarily difficult. Inflation remains far above their targets, and some of the latest data have been going in the wrong direction. But credit growth is bound to be hammered by the ructions of recent days, powerfully affecting the economic outlook.

The European Central Bank set the initial tone of the response on Thursday, seeking to deal with the dual challenges on separate fronts. President Christine Lagarde and her colleagues stuck with their plan to raise rates by 50 basis points, but they refrained from giving any guidance on where policy will go from here. The ECB said it’s ready to respond on both price and financial stability.

A similar judgment by the Federal Reserve would see them hike by at least 25 basis points next week, while being more circumspect on what happens thereafter. The bond market’s conclusion: wherever the eventual peak in rates was for the ECB, Fed, and others at the start of this month, it’s lower now.

“It’s probably the most aggressive repricing of monetary policy globally we’ve had, certainly since the 1980s,” Ella Hoxha, a senior investment manager at Pictet Asset Management, said on Bloomberg Television. “The market is in a seek-and-destroy mode,” making it very difficult to predict how things pan out, she said.

Silicon Valley Bank was the first key sign that the Fed’s cumulative 4.5 percentage points of tightening over the past year is causing financial breakage. Its collapse, along with regulators’ seizure of Signature Bank, quickly metastasized into a broader selloff in US regional banks and even increased scrutiny of the troubles of Credit Suisse — an officially designated global systemically important bank.

The sudden eruption of financial-stability risks comes just after policymakers had doubled down on the need for higher rates to ensure rampant cost pressures will be contained. That’s sparked debate among economists and investors over whether central banks will be able to separate the two perils.

The Fed on Sunday set up a new facility aimed at securing confidence in smaller banks’ deposits. The Swiss National Bank — which has also been steadily raising rates — injected liquidity into Credit Suisse in a move early Thursday morning. And the ECB said its toolkit is “fully equipped to provide liquidity support” to the financial system as needed.

Economists at JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp. are among those arguing that, in the Fed’s case, the separation principle with regard to financial-stability and inflation tools should hold.

“Our view is that ultimately the ring-fencing works and the Fed goes back to hiking interest rates,” Ethan Harris, Bank of America’s head of global economics research, said on Bloomberg TV earlier this week, referring to the regulatory response to the bank failures. “Ultimately the Fed is going to end up having to fight inflation.”

Not everyone sees such a neat line, however. Jan Hatzius at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. sees the Fed scrapping next week’s rate move amid the continuing turmoil.

For their part, Nomura Holdings Inc. economists see a wholesale shift in Fed policy toward damage control, with a rate cut coming on March 22.

Futures markets show divided bets on whether Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues will boost their benchmark by a quarter point next week. But they suggest policymakers will start lowering rates this summer. Bond investors were sent scrambling yet again to reverse prior moves. Two-year US yields jumped 27 basis points to post their sixth-straight day of shifting by at least 20 basis points.

Swaps contracts underscore the massive reversal in expectations in recent days. On March 8, a full percentage point of Fed rate hikes were priced in by June; now, they see a 50-50 chance the Fed will start cutting borrowing costs by then. It’s been a similar — though less stark — trend across major developed economies, outside of Japan. Even after the ECB hiked overnight, traders expect a much lower eurozone rate in six months from now than they were projecting last week.

Here’s a recap of the week that saw the shift from easy money to costly credit rack up casualties and spur the biggest bond market repricing in decades.

Hawkish talk

Speaking before the West Coast lender SVB became a universally recognized name, Powell in two days of testimony before Congress last week warned that robust US data made it likely the Fed’s peak rate would be higher than officials had penciled in in December.

That sent two-year US yields above 5% for the first time since 2007. Traders priced in steeper and steeper hikes. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, a paid contributor to Bloomberg TV, said the odds were almost even the Fed would have to raise its benchmark interest rate to 6%.

SVB’s demise

SVB’s unraveling had all the more impact given that hawkish Fed backdrop. News of the bank’s struggles turbo-charged a bond rally that had started when some economic data signaled the US labor market might be turning less hot.

Liquidity evaporated across parts of the Treasuries and rates markets as fast-money quants scrambled to close out some $300 billion of wagers on higher yields that were now deeply out of the money.

The slump in yields accelerated on Friday to the sort of pace last seen when Lehman Brothers went under in 2008, as SVB lurched toward its own collapse. The lender was placed into Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. receivership.

A note from a Goldman Sachs trading desk said, on a scale of 1 to 10, last Thursday and Friday were an “8” in terms of how frantic customers were. Brevan Howard Asset Management reportedly grounded at least three rates traders to stem losses after the collapse of SVB triggered wild moves in markets.

Regulators step in

The weekend brought little comfort, even after the Fed and US regulators stepped in to make sure depositors at SVB — and at another failed lender, Signature Bank — would get their money back. Treasuries extended their rally to the strongest since the 1980s, with every part of the yield curve flashing recession warnings.

The SVB crisis looks like a “canary in the coal mine,” said Bridgewater Associates founder Ray Dalio. BlackRock Inc. Chief Executive Officer Larry Fink contemplated the potential for other dominoes to fall.

Woes deepen

While the latest US inflation reading — the February consumer price index — on Tuesday showcased that price pressures remain too high for the Fed — markets were further whipsawed by the troubles tied to Credit Suisse.

“The problem is that Credit Suisse, by some standards, might be too big to fail, but also too big to be saved,” Nouriel Roubini warned Wednesday on Bloomberg Television. The economist who’s known as “Dr. Doom” added that it’s not clear the bank’s regulators have the resources to engineer a sufficient bailout.

By Thursday morning on Wall Street, the zeitgeist seemed a world away from a global financial crisis level of alarm. Bond yields moved higher after Switzerland’s central bank gave Credit Suisse a 50 billion franc ($54 billion) credit line and reports that First Republic Bank — the latest US lender to wobble — will get as much as $30 billion in deposits from the nation’s banks.

Into Asia’s morning Friday and equities were poised to follow US shares higher. Australian shares rose while stock futures for benchmarks in Japan and Hong Kong gained at least 1%. But with the Fed meeting looming next week, markets will remain on edge for a while yet.

“The fact that stresses reveal themselves is just a symptom of hiking cycles and tightening liquidity,” said Amy Xie Patrick, head of income strategies at Pendal Group Ltd. in Sydney. “It’s supposed to happen this way.”

© 2023 Bloomberg