The cargo trapped for months at the Dutch port of Rotterdam was so precious that the United Nations intervened to mediate its release. The World Food Programme chartered a ship to transport it to Mozambique, from where it’s being taken by truck through the interior to its end destination, Malawi.

It’s not grain or maize, but 20 000 metric tons of Russian fertiliser, and it can’t come soon enough.

About 20% of Malawi’s population is projected to face acute food insecurity during the “lean season” through March, making the use of fertilisers to grow crops all the more vital. It’s one of 48 nations in Africa, Asia and Latin America identified by the International Monetary Fund as most at risk from the shock to food and fertiliser costs fanned by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. One year on, the upheaval caused to world fertiliser markets is seen by the UN as a key risk to food availability in 2023.

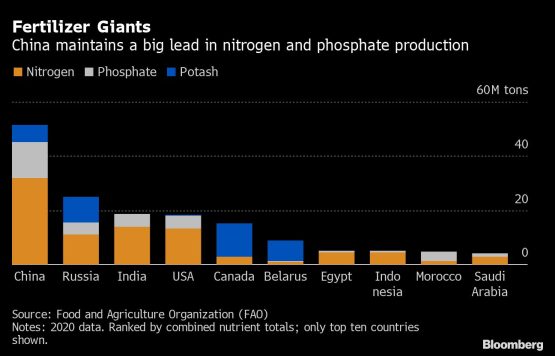

Yet alongside humanitarian considerations, it’s the realisation that much of the world relies on just a few nations for most of its fertilisers — notably Russia, its ally Belarus and China — that’s ringing alarm bells in global capitals. Just as semiconductors have become a lightning rod for geopolitical friction, so the race for fertilisers has alerted the US and its allies to a strategic dependency for an agricultural input that is a key determinant of food security.

That’s pushed fertilisers — and who controls them — to the forefront of the political agenda around the world: The US State Department is beefing up its expertise on fertilisers, presidents are tweeting about them, they’re featuring in election campaigns, and becoming the focus of tensions between countries as well as an unlikely currency of diplomacy. They’re also being pulled into the contest of narratives over who’s to blame for the fallout from Russia’s war on Ukraine.

“The role of fertiliser is as important as the role of seed in the country’s food security,” said Udai Shanker Awasthi, managing director and chief executive officer of the Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative, the country’s largest producer. “If your stomach is full then you can defend your house, you can defend your borders, you can defend your economy.”

Stored potash at the Nutrien Cory potash mine in Saskatoon, Canada in November. Image: Heywood Yu/Bloomberg

Last year’s jolt to the $250 billion global fertiliser industry highlighted the role of Russia and Belarus as exporters of almost a quarter of all world crop nutrients. While Russia’s agricultural products including the three main types of fertiliser — potash, phosphate and nitrogen — are not targeted by sanctions, exports remain curtailed through a combination of disruptions to ports, shipping, banking and insurance.

Andrey Melnichenko. Image: Bloomberg

Russian fertiliser billionaire Andrey Melnichenko, the founder of EuroChem Group AG, argues the European Union’s sanctions regime has clogged up trade to such an extent that it’ll have caused a total curtailment of fertiliser shipments by some 13 million tons by the one-year mark of the war on February 24. Melnichenko is himself subject to sanctions.

It was Russian fertiliser caught in limbo in the Netherlands that was freed as part of a wider UN deal to allow grain transports via the Black Sea. The batch that began arriving in Malawi earlier in February was the first of several proposed shipments of fertiliser stranded in ports from the Baltic Sea to Belgium and “donated” by Russia’s Uralchem-Urakali Group. Uralchem is planning a handover ceremony with Malawi’s government to be attended by the Russian ambassador on March 6.

The market disruption triggered a spike in prices last summer that led to stockpiling by those able to afford fertilisers, and while costs have since come down significantly, they remain above pre-pandemic levels. Supplies are constrained in poorer areas. The situation is exacerbated by sanctions on potash giant Belarus alongside the decision by China, a major producer of nitrogen and phosphate fertilisers, to impose restrictions on exports to protect domestic supply, curbs that analysts don’t see being lifted until the middle of 2023 at the earliest.

The result has been an all-too familiar divide: Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Alexis Maxwell says that even though prices have fallen more than 50% from last year’s peak, farmers in Southeast Asia and Africa remain more exposed than their counterparts in North America, China or India. The African Development Bank has warned that curtailed use is likely to mean a 20% drop in food production, while the WFP sees smallholders in the developing world at risk of “a major food availability crisis as the fertiliser crunch, climate shocks and conflict upend food production.”

Indonesian President Joko Widodo warned at the Group of 20 summit he hosted in November of “a more dismal year” ahead without immediate steps to ensure availability of affordable nutrients. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who now holds the G-20 chair, pledged to focus efforts to “depoliticise” global fertiliser supply, “so that geopolitical tensions do not lead to humanitarian crises,” he wrote in the Times of India in December.

The geopolitical fallout is being felt as far away from Ukraine as Canada, the world’s biggest potash producer (Russia and Belarus are No. 2 and No. 3 respectively). Brazil’s agriculture minister traveled there immediately after the war’s outbreak to secure more shipments for the food-exporting superpower, while Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government has said it’s looking at increasing exports to Europe of “strategic commodities” including potash.

Nutrien, the world’s largest fertiliser company and the biggest private employer in its home base of Saskatoon in Canada, is expanding production at its potash mines, helping fuel the city’s spread out into the great prairie lands of central Saskatchewan. BHP Group gave the green light to build its own massive potash mine in Saskatchewan about 18 months ago; it’s already looking at options to accelerate an expansion that would see total output double.

Nutrien mines potash from a 400 million-year-old rock known as the Prairie Evaporite Formation at a depth of some 1 000 metres. This far down, the heat is a stark contrast with the sub-zero temperatures outside in the Saskatchewan winter. The air has an ocean tang that comes from the high concentration of salt in the potash. Huge boring machines cut tunnels to extract the ore, which is moved by conveyors to underground storage areas, then taken to the surface and on-site mills.

The Saskatoon-based company is targeting a 40% increase in production from 2020 levels by 2026. “We think the world’s going to need it,” says Ken Seitz, Nutrien’s chief executive officer. He cites the “knock-on effect of all this geopolitical uncertainty,” adding: “It’s going to be bumpy.”

The UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation set up a trade tracker last year showing that many net importers in Latin America, eastern Europe and Central Asia depend on Russia for more than 30% of all three main fertiliser ingredients.

Plant tissue samples at Nutrien Ag Solutions Breeding Facility in Saskatoon. Image: Heywood Yu/Bloomberg

And in Ukraine, regarded for years as Europe’s breadbasket, Agriculture Minister Mykola Solskyi warned in January that this summer’s grain harvest will be affected, since fewer nutrients were purchased and applied in the fall.

The race for fertiliser supplies has spawned efforts to encourage self-sufficiency. In an echo of the Chips Act that made $50 billion available for US semiconductor production, President Joe Biden’s administration has announced $500 million in grants to increase “American-made fertiliser production” and “bring production and jobs back to the United States.”

The US both produces fertiliser and is a major importer, and for now its farmers still have access to plenty of nutrients. That can’t be said of some of its neighbours. Latin America depends on imports for 83% of fertilisers applied, mostly from Russia, China and Belarus, according to the Washington-based International Food Policy Research Institute.

That’s looking like a liability for Peru and its burgeoning agricultural industry. The Andean nation, perennially convulsed by political upheaval, has recorded a rare success story in its fruit and vegetable sector in recent years. It’s now the world’s No. 1 exporter of blueberries and a key supplier of avocados, asparagus, artichokes and mangoes in an industry predicted to be worth some $10 billion to the country this year.

But further growth and efforts to integrate smallholders into modernised industry practices have been cast in doubt as Peru struggled to access fertiliser. The previous government announced subsidies for the smallest farmers, but implementation was patchy, said Valeria Pineiro, IFPRI’s acting head for Latin America.

On several occasions the government tried and failed to secure imports. In the absence of alternatives, it began supporting a program to increase use of organic fertilisers from seabird excrement, known as guano. But that doesn’t nearly cover what’s needed, said Gabriel Amaro, head of Peru’s agricultural export association AGAP. “The small farmer hasn’t necessarily been able to apply fertiliser, or has applied very little,” meaning loss of productivity and even damage to plants, he said.

Peru “is being hit hard,” said Pineiro. It’s faced with some big problems, and “they’re all political.”

If Peru is a loser of the fertiliser crisis, then Morocco is one of its winners, and it’s deploying that new-found clout to political ends.

Thanks to geological good fortune, Morocco is home to 70% of the world’s known reserves of phosphate, the natural source of phosphorous, a core nutrient used in fertiliser. That makes Morocco and state-owned OCP Group, which is responsible for mining, processing, manufacturing, and exporting phosphorous, pivotal to food security in a world that’s being reshaped by Russia’s war.

The North African country has made little secret of using fertiliser donations and subsidised sales to promote its aspirations to regional leadership. “Rabat has used OCP’s exports as a foreign policy instrument, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa,” Michael Tanchum, a professor of political economy, wrote in a blog for the Middle East Institute, citing its sales, local investment and development outreach.

OCP is state-owned but with a separate and distinct identity from the government, Executive Vice-President Nada El Majdoub said in an emailed response to questions. “Having said that, clearly the interests of the government and of OCP frequently align, and particularly in respect of OCP’s mission to strengthen sustainable agricultural practices and productivity across Africa,” she said.

OCP has committed to double its supply of fertiliser to Africa in 2023 to about four million tons, on top of donating and supplying discounted fertiliser of more than 500 000 tons last year. While that is a humanitarian gesture welcomed by USAID among others, some see a benefit for Morocco, too.

Morocco is embroiled in a dispute with neighbouring Algeria over the status of the Western Sahara, and fertiliser plays a role. Relations have deteriorated since a three-decade cease-fire collapsed in 2020, reigniting low-key hostilities between Morocco and Algeria-based Saharawis seeking independence. Where authorities in Rabat see militant secessionists, some in Latin America and Africa see a liberation movement and recognise the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) as an independent state.

In September, Kenya’s new president, William Ruto, took a call from Morocco conveying King Mohammed’s congratulations, after which Ruto announced to his 5.6 million Twitter followers that Kenya was rescinding its recognition of the Saharawi region. Morocco’s Foreign Ministry hailed the move and announced the countries were deepening trade relations, including in the field of “food security (fertiliser importation).” Bags of nutrients began arriving shortly after, even though Ruto subsequently deleted his tweet.

Peru took the opposite tack, announcing it was renewing diplomatic ties with the Saharawis, and appears to have suffered the consequences. The Morocco World News reported that a planned shipment of some 150 000 tons of fertiliser bound for Peru had been canceled after the change in stance.

President Vladimir Putin blames sanctions for the disruption in fertiliser supply from Russia, saying in late November that more than 400 000 tons were frozen in European ports. A portion of that amount has since been unfrozen and donated. The UN says the core problem lies with shipping insurers unwilling to cover Russian cargoes, and with key agriculture banks being unable to make financial transactions since they are disconnected from SWIFT. The EU and US issued a joint statement in November clarifying that “banks, insurers, shippers, and other actors can continue to bring Russian food and fertiliser to the world.”

Sufficient affordable supplies are still not getting through to Malawi, which is dependent upon fertiliser donations. The first low-income nation to receive financing from the IMF last year under a new tool intended to help countries cope with global food price shocks, Malawi was already struggling with debt, a currency devaluation and drought. In October, it transpired that a UK company the government had paid 750 million kwacha ($710 000) for fertiliser was in fact a butcher and unable to fulfil the contract.

President Lazarus Chakwera acknowledged the “challenges to access fertilisers” during a November ceremony for a subsidy program for poor households, and promised the government was doing everything to recoup the money.

That’s not much comfort to Moses Mikayeli, a farmer from Chikusa Village just outside Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe, who said in late November that he saw “no hope” of receiving the subsidised fertiliser promised by the government. Bags were available, but at 70,000 Kwacha apiece – almost five times the price pledged by the president and 14 times the price in 2021 — they were beyond the reach of most. So he was resorting to a mix of garbage, soil and pig dung to spread on his maize.

“Our soils are used to fertiliser, so without applying fertiliser we can’t harvest anything,” he said. “Our situation remains dire.”

© 2023 Bloomberg