A month ago South Africans heard some hard truths about the state of the power utility, Eskom, from the outgoing CEO André de Ruyter. In an interview broadcast on television, De Ruyter made accusations about the role of criminal gangs as well as politicians in corruption that’s crippled the utility. The interview triggered his immediate departure – he was due to leave some weeks later – as the ruling African National Congress rounded on him.

But, in my view, South Africans – particularly the new Minister of Electricity Kgosientsho Ramokgopa – would be well advised to look more carefully at what De Ruyter said, rather than trying to discredit the messenger.

De Ruyter outlined four levels at which Eskom is being destroyed.

Firstly, there is the issue of a lack of political support from Cabinet for a renewal strategy for Eskom which De Ruyter attempted to implement. The plan included dealing with crime, separating the existing entity into three different companies (generation, transmission and distribution) and over time, decarbonising energy generation. Effectively this meant, over time, closing coal-fired power stations and replacing them with renewable energy storage capability.

Secondly, De Ruyter outlined how Eskom continues to be infiltrated by systematic corruption involving private individuals and companies using public assets for personal gain. The pattern of state capture began in earnest under the presidency of Jacob Zuma but these players have continued to hold onto powerful interests within the company, including contracts for coal, construction and maintenance. They are principally rent-seekers, and extract money for no added value.

Thirdly, there is organised crime. These groups are distinct from the agents of state capture. They control how money flows as well as the operations of several power stations. For instance, Eskom has lost control of Tutuka, one of the bigger coal-fired power stations that should be generating at least three GW (12% of the total demand). Yet energy availability from the plant is now an eye-watering 12% of its capacity.

Finally, De Ruyter identified intentional malfunction and petty crime as a major threat. Anyone who can break the law does so without consequence.

Much of the resource and power that are necessary to solve problems at all four levels are in the Minister of Electricity’s or government’s control. He needs to get Cabinet behind a renewal strategy that aligns with the global energy transition, he needs to get the police to do their job with competence, and he needs a powerful CEO who has local legitimacy and support.

And he needs to act immediately.

The depth of the crisis

South Africa’s electricity supply crisis has never been more severe. This is clear from the data that Eskom publishes on its data portal.

Power cuts – known locally as load shedding – have now risen to 15% of total demand. This means that, on average, embattled customers are without power for at least 5.5 hours for each 24 hour cycle (see figure below).

David Richard Walwyn

As the figure shows, load shedding rises every month, with February being the worst on record ever.

(The data in the graph is based on actual dispatched generation versus the anticipated demand, where the latter is obtained by Eskom from historical patterns of use.)

Just when South Africans had hoped that the situation could improve, it deteriorated. In May last year, load shedding was a 2% of the total demand. At the time they still had confidence in President Cyril Ramaphosa’s ability to solve the crisis with his six-point action plan.

Since then the country has endured a string of broken promises, heard explosive revelations from the De Ruyter interview and witnessed the further collapse of the coal fleet.

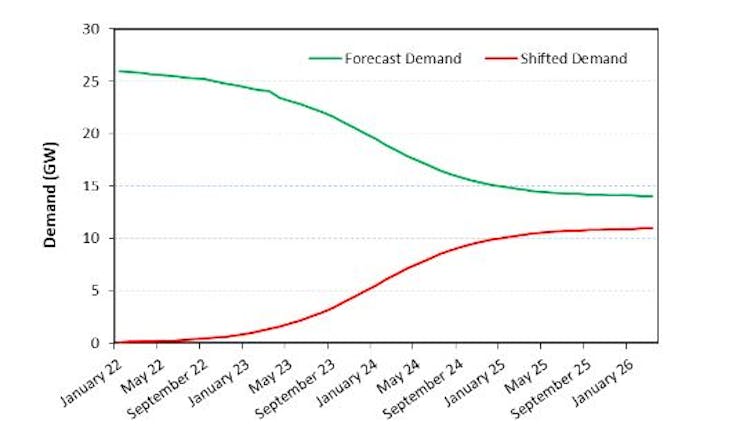

The longer the crisis lasts, the more Eskom’s energy market will shrink. Using the data from the last few years, it is possible to model what is happening to energy demand and what could happen in the future.

About nine GW of Eskom’s customer base are untouchable – these customers are unaffected by Eskom and unlikely to source alternative supply. We also know that about nine GW of demand mainly allocated to the Energy Intensive Users Group, will be replaced by in-house generation over the next two to three years.

Combined with the growing use of rooftop solar in residential and commercial buildings, my prediction, based on my modelling studies, is that by March 2026, the shifted demand will be 11 GW, leaving a residual demand on the national grid at 14 GW, or about 40% of the average demand in 2020.

David Richard Walwyn

If Eskom cannot sell the electricity that it generates, operating costs will quickly outstrip revenue. The challenge is therefore not only to rebuild generation, but also to keep high value customers, who are switching to solar.

What will help

All eyes are on the new Minister of Electricity. Does he have the skills, energy and political influence to resolve the energy crisis? Or will his appointment further obfuscate an already incoherent portfolio?

Minister Ramokgopa needs to add three important tasks to his programme of action. He needs to learn from the De Ruyter interview (and address the problems he identified), he needs to rapidly unbundle Eskom and he needs to solve problems that are delaying the implementation of the renewable energy programme.

In his budget speech, Minister Enoch Godongwana made it clear that the establishment of the National Transmission Company of South Africa is a priority. Although National Treasury will borrow R254 billion to refloat Eskom, the funds can only be used to secure and extend the assets of the transmission company. The implications of this position are clear – sell off the generation capacity to private investors and leave distribution to local authorities, where this is possible.

One aspect of the De Ruyter interview which has been largely ignored is the issue of the renewable energy programme and how this has been derailed despite its obvious benefits in terms of lower energy cost and minimal water usage. As De Ruyter mentioned, if the programme had remained on track, South Africa would have avoided 98% of the 2022 load shedding.

In addition, the closure of several Eskom coal-fired water-cooled power stations will release billions of litres of water for use in domestic applications, savings which will become essential for a water-scarce country. Closure of these stations will also deal with the air quality concerns and the ongoing breaches by Eskom of its emissions permits.

It is apparent, now, that nothing will save Eskom in its present configuration. It will join a list of state-owned entities that are a fraction of their former scale – the Post Office, South African Airways, the Passenger Rail Association of South Africa.

How far it sinks will depend on how effective Minister Ramokgopa can be in his new position.![]()

David Richard Walwyn, Professor of Technology Management, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.