Rafael Grossi slipped into Moscow a few weeks ago to meet quietly with the man most Westerners never engage with these days: President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia.

Mr. Grossi is the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog, and his purpose was to warn Mr. Putin about the dangers of moving too fast to restart the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, which has been occupied by Russian troops since soon after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

But as the two men talked, the conversation veered off into Mr. Putin’s declarations that he was open to a negotiated settlement to the war in Ukraine — but only if President Volodymyr Zelensky was prepared to give up nearly 20 percent of his country.

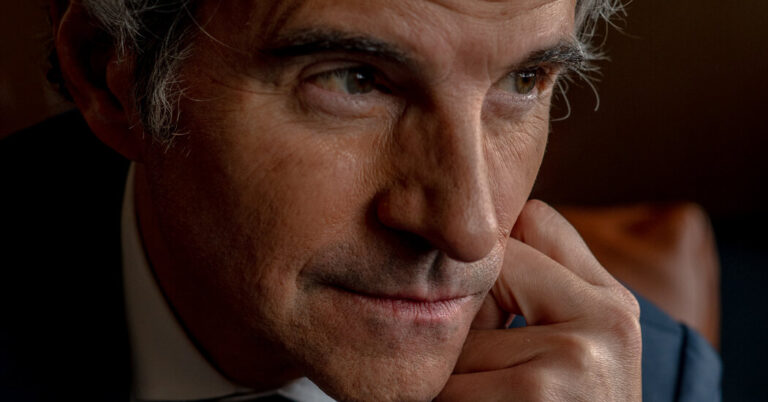

A few weeks later, Mr. Grossi, an Argentine with a taste for Italian suits, was in Tehran, this time talking to the country’s foreign minister and the head of its civilian nuclear program. At a moment when senior Iranian officials are hinting that new confrontations with Israel may lead them to build a bomb, the Iranians signaled that they, too, were open to a negotiation — suspecting, just as Mr. Putin did, that Mr. Grossi would soon be reporting details of his conversation to the White House.

In an era of new nuclear fears, Mr. Grossi suddenly finds himself at the center of two of the world’s most critical geopolitical standoffs. In Ukraine, one of the six nuclear reactors in the line of fire on the Dnipro River could be hit by artillery and spew radiation. And Iran is on the threshold of becoming a nuclear-armed state.

“I am an inspector, not a mediator,” Mr. Grossi said in an interview this week. “But maybe, in some way, I can be useful around the edges.”

It is not the role he expected when, after a 40-year career in diplomacy that was focused on the nuts and bolts of nonproliferation, he was elected director-general of the agency by the barest majority after the sudden death of his predecessor, Yukiya Amano. That was “before anyone could imagine that Europe’s largest nuclear power plant would be on the front line of a war,” he said in one of a series of conversations at the agency’s headquarters in Vienna, or that Israel and Iran would exchange direct missile attacks for the first time in the 45 years since the Iranian revolution.

Today he has emerged as perhaps the most activist of any of the I.A.E.A.’s leaders since the agency was created in 1957, an outgrowth of President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” program to spread nuclear power generation around the globe. He has spent most of the past four and a half years hopping the globe, meeting presidents and foreign ministers, pressing for more access to nuclear sites and, often, more authority for an organization that traditionally has had little power to compel compliance.

But along the way, he has been both a receiver and sender of messages, to the point of negotiating what amounts to a no-fire zone immediately around Zaporizhzhia.

Mr. Grossi has his critics, including those who believe he acted beyond his authority when he stationed inspectors full-time in the embattled plant, at a moment when armed Russians with little knowledge of nuclear power were patrolling the control room. He was also betting that neither side would want to attack the plant if it meant risking the lives of United Nations inspectors.

It worked. Jake Sullivan, President Biden’s national security adviser, recalls being so concerned about a nuclear disaster early in the Ukraine conflict that he had the head of the National Nuclear Security Administration on the phone describing what would happen if a reactor was struck and a deadly radioactive cloud wafted across Europe. “It was a terrifying scenario,” he said later.

Two years later, “we are moving into a period of protracted status quo,” Mr. Grossi said. “But from the beginning I decided I could not just sit on the sidelines and wait for the war to end, and then write a report on ‘lessons learned.’ That would have been a shame on this organization.”

On the Battlefield, an Unusual Inspection

The I.A.E.A. was created to do two things: keep nuclear power plants safe and prevent their fuel and waste product from being spirited away to make nuclear weapons. Agency inspectors don’t search for or count the weapons themselves, though many in Congress — and around the world — believe that is its role.

Mr. Grossi was born in 1961, four years after the agency’s creation. He started his career in the Argentine foreign service, but his real ambition was to run the I.A.E.A., with its vast network of highly trained inspectors and responsibility for nuclear safety around the globe. It was a burning ambition.

“I feel like I prepared for this my whole life,” he said in 2020.

Many might wonder why. It is the kind of work that traditionally involves lengthy meetings in bland conference rooms, careful measurements inside nuclear plants and setting up tamper-resistant cameras in key facilities to assure that nuclear material is not diverted to bomb projects.

The work is tense, but usually not especially dangerous.

So it was unusual when Mr. Grossi, exchanging his suit for a bulletproof vest, stepped out of an armored car in southeastern Ukraine in late summer 2022, as shells exploded in the distance. He had rejected an offer from the Russians to escort him in from their territory. As a very visible United Nations official, he did not want to lend any credence to Moscow’s territorial claims.

Instead, he took the hard route, through Ukraine, to a wasteland littered with mines and destroyed vehicles. As he neared the plant a Ukrainian guard stopped him, saying he could not go further, and was unimpressed with the fact that Mr. Zelensky himself had blessed the mission.

But after hours of arguments, Mr. Grossi ignored the guard and proceeded anyway, inspecting the plant and leaving a team of inspectors behind to put all but one of its reactors into cold shutdown.

On a rotation, small teams of U.N. inspectors have remained there every day since.

It was the kind of intervention the agency had never made before. But Mr. Grossi said the situation required an aggressive approach. Europe’s largest nuclear complex “sits on the front line,” Mr. Grossi said.

“Not near, or in the vicinity,” he emphasized. “On the front line.”

In St. Petersburg, a Meeting With Putin

A month after that first visit to the plant, Mr. Grossi traveled to St. Petersburg to meet directly with Mr. Putin, planning to make his case that if the continued shelling took out cooling systems or other key facilities, Zaporizhzhia would be remembered as the Putin-triggered Chernobyl. To drive home the point, he wanted to remind Mr. Putin that, given the prevailing winds, there was a good chance that the radioactive cloud would spread over parts of Russia.

They met at a palace near the city, where Mr. Putin had risen through the political ranks. Mr. Putin treated the chief nuclear inspector graciously, and clearly did not want to be seen as obsessed by the war — or even particularly bothered by it.

Once they dispensed with pleasantries, Mr. Grossi got right to the point. I don’t need a complete cease-fire in the region, he recalled telling the Russian leader. He just needed an agreement that Mr. Putin’s troops would not fire on the plant. “He didn’t disagree,” Grossi said a few days later. But he also made no promises.

Mr. Putin, he recalled, didn’t seem confused or angry about what had happened to his humiliated forces in Ukraine, or that his plan to take the whole country had collapsed. Instead, Mr. Grossi noted, the Russian leader was focused on the plant. He knew how many reactors there were and he knew where the backup power supplies were located. It was as if he had prepared for the meeting by memorizing a map of the facilities. “He knew every detail,” Mr. Grossi said. “ It was sort of remarkable.”

For Mr. Putin, Zaporizhzhia was not just a war trophy. It was a key part of his plan to exercise control over all of Ukraine, and help intimidate or blackmail much of Europe.

When Mr. Grossi met Mr. Putin again, in Moscow earlier this spring, he found the Russian leader in a good mood. He was full of plans to restart the plant — and thus assert Russian control over the region, which Russia claims it has now annexed. Mr. Grossi tried to talk him out of taking the action, given the “fragility of the situation.” But Mr. Putin said the Russians were “definitely going to restart.”

Then the conversation drifted into whether there could be a negotiated settlement to the war. Mr. Putin knew that whatever he said would be conveyed to Washington. “I think it is extremely regrettable,” Mr. Grossi said a few days later, “that I am the only one talking to both” Russia and the United States.

In Iran, an Old Challenge Revived

Dealing with Iran’s leadership has been even more delicate, and in many ways more vexing, than sparring with Mr. Putin. Two years ago, not long after the I.A.E.A. board passed a resolution condemning Tehran’s government for failing to answer the agency’s questions about suspected nuclear activity, the Iranians began dismantling cameras at key fuel-production facilities.

At the time, Mr. Grossi said that if the cameras were out of action for six months or so, he would not be able to offer assurances that fuel had not been diverted to other projects — including weapons projects. That was 18 months ago and since then, the Iranian parliament has passed a law banning some forms of cooperation with agency inspectors. Meanwhile, the country is steadily enriching uranium to 60 percent purity — perilously close to what is needed to produce a bomb.

Mr. Grossi has also been barred from visiting a vast new centrifuge plant that Iran is building in Natanz, more than 1,200 feet below the desert surface, some experts estimate. Tehran says it is trying to assure that the new facility cannot be bombed by Israel or the United States, and it insists that until it puts nuclear material into the plant, the I.A.E.A. has no right to inspect it.

Last week, Mr. Grossi was in Tehran to take up all these issues with the foreign minister, Hossein Amir Abdollahian, and with the head of Iran’s atomic energy agency. It was just weeks since Iran and Israel had exchanged direct missile attacks, but Mr. Grossi did not detect any immediate decisions to speed up the nuclear program in response.

Instead, Iranian officials seemed pleased that they were being taken seriously as a nuclear and a missile power in the region, increasingly on par with Israel — which already has a small nuclear arsenal of its own, though one it does not officially acknowledge.

There was some discussion of what it would take to revive the 2015 nuclear deal that Iran signed with the Obama administration, though Biden administration officials say the situation has now changed so dramatically that an entirely new deal would be required.

“I suspect,’’ Mr. Grossi said this week, “I will be back in Tehran frequently.”