It was an embrace that held 74 years of ache and longing. As Sikka Khan, 75, fell into the arms of his older brother Sadiq Khan, now in his 80s, the pair wept with simultaneous sorrow and pleasure. More than seven decades had handed for the reason that brothers, torn aside by the horrors of partition, had seen one another. With Sikka in India and Sadiq in Pakistan, neither knew if the opposite was alive. Yet each had by no means stopped wanting.

But on a crisp January afternoon this 12 months, the pair had been reunited alongside the border that had so devastatingly fractured their household. “Finally, we are together,” Sadiq instructed his brother, tears streaming down his face.

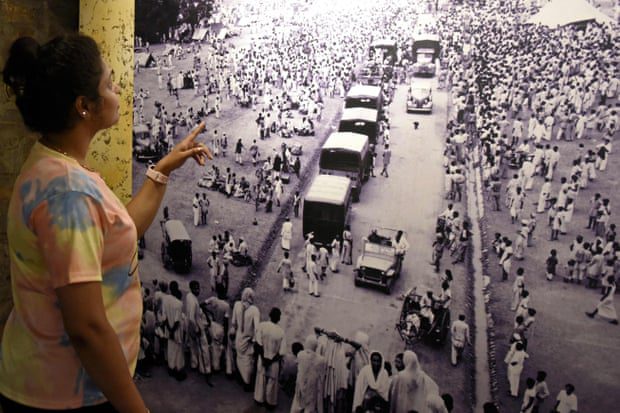

It was 75 years in the past, on 15 August 1947, that the subcontinent was divided down spiritual traces to grow to be two unbiased international locations, India and Pakistan. It was to be a bloody and bitter partition. After 300 years of official British presence, the important thing figures of Indian independence, Mahatma Gandhi and his protege and future prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, envisaged a single, secular nation. Muslim political chief Muhammad Ali Jinnah, nevertheless, argued for a separate state for Muslims, petrified of the implications of a Hindu-majority India.

As spiritual tensions had been stoked, lethal riots broke out, focusing on Hindus, then Muslims after which Sikhs. The British, eager to extricate themselves from India shortly, oversaw the drawing of a crude border that ruptured the Indian states of Punjab to the west and Bengal to the east, to kind a disjointed Pakistan that angered all communities.

It instigated a mutual genocide on either side of the brand new border. Whole villages had been set alight, youngsters had been massacred, and an estimated 75,000 ladies had been raped. In Punjab, the centre of the violence, pregnant ladies had infants reduce from their bellies and trains filled with refugees – Muslims fleeing Indian Punjab, Sikhs and Hindus fleeing western Pakistan – had been ambushed and arrived at stations crammed with silent bloody corpses.

The true dying toll continues to be unknown, with estimates starting from 200,000 as much as 2 million, and it resulted within the largest pressured migration in historical past as greater than 14 million folks fled their houses. From that time onward, India and Pakistan had been sworn enemies, break up by a border that over decades would grow to be more and more fractious and impenetrable.

Families caught within the chaos and brutality had been pressured to go away the whole lot behind and plenty of had been separated as they crossed into India or Pakistan. Though many tried desperately to seek out one different later, by way of newspaper adverts, letters and messages on noticeboards, cross-border communication was restricted. Visa restrictions and a deep-rooted concern of the “other side” additionally prevented most from ever going again over the border.

But just lately, social media has opened up a realm of recent prospects. Facebook pages and YouTube channels, some with 1000’s of members from India and Pakistan, have begun to reconnect folks with the houses and members of the family misplaced throughout partition and the ensuing battle that additionally break up Kashmir.

Video accounts and fragments of knowledge are posted on the pages: a photograph or identify, a village, or an outline of a home. As the posts are shared broadly by folks on either side of the border, and by the diaspora the world over, they generally flip up leads. While getting a visa to cross the border continues to be a problem, video calls have been organized so that individuals can see the houses and villages they had been pressured to go away behind so way back.

“For those who lived through partition, that yearning for their origins remains very strong,” mentioned Aanchal Malhotra, an creator who has spent years documenting the oral historical past of partition.

“One of the most common things I hear in my research is ‘When I close my eyes, I see my home’ or ‘Every night in my dreams, I cross the border.’ Most people have resigned themselves to the fact they will never see their homes again. But the great power of social media is that it is borderless and it’s been beautiful to see the way it’s been used in India, in Pakistan, in Bangladesh, to connect people to a past they thought they had lost.”

Makhu Devi, 87, who lives in Indian-controlled Kashmir, mentioned she had been given a brand new lease of life after a Facebook group had just lately related her to kinfolk nonetheless dwelling in her outdated village, now in Pakistan, which she was pressured to flee. They now have common cellphone calls, although the primary few instances everybody hardly spoke, as they had been crying too closely. “My memory gets refreshed,” mentioned Devi of the calls. “I am taken back to those times. I feel as young and energetic as I was then.”

Second and third generations have additionally embraced social media teams, to hook up with an ancestry which frequently goes undiscussed in families amid a pervasive tradition of silence round partition. Lines of cross-border communication have been opened up in modern methods, together with through dating apps. On Instagram it has grow to be widespread for folks to seek for hashtags of the cities or villages the place their grandparents got here from to see what they seem like now and discover folks nonetheless dwelling there.

Punjabi Lehar, a YouTube channel arrange by Nasir Dhillon, 38, an actual property vendor from Faisalabad Punjab in Pakistan, has made about 800 movies serving to folks reconnect with an individual or a spot misplaced in partition. According to his estimates, 300 have led to in-person reunions between family members who had been separated by the India-Pakistan border.

Dhillon grew up listening to his household and village elders speak longingly of the ancestral villages they may now not go to, and he started utilizing social media to share their tales and collect data. But after his posts and movies started to go viral, “the response was so overwhelming that I realised this is the story of the entire Punjab”.

“Whatever I am doing is because of my roots,” mentioned Dhillon. “We might be living in two hostile countries, but our hearts are still in pre-partition time. I pray there is never a partition like this anywhere in the world – it is a cruel thing.”

Sign as much as First Edition, our free day by day publication – each weekday morning at 7am BST

His best remorse is that he couldn’t take his father, who died in 2018, to their ancestral household shrine in India, which he lastly managed to find due to social media. “He was longing to see his native village till the last days,” mentioned Dhillon. He has not but been in a position to go to it both; final 12 months India rejected his visa utility.

It was due to Dhillon’s channel that the Khan brothers discovered one another once more. Sikka, who was born to a Muslim household in what’s now Indian Punjab, was simply six months outdated when partition violence broke out. Away from house together with his mom, they had been pressured to take shelter with an area Sikh household who had been defending their Muslim neighbours from the massacres.

After weeks of carnage, they emerged, however to horrible scenes. The close by river was so crammed with our bodies it ran pink with blood. And in Sikka’s house village of Jagraon 40 miles away, there have been no Muslims left; no hint of Sikka’s father, his 10-year-old brother or eight-year-old sister. Sikka’s mom, consumed with grief, drowned herself. Sikka was left with no household besides a penniless uncle, and was raised by a Sikh household from his mom’s village.

He spent his complete grownup life looking for information of his household, notably his beloved brother Sadiq. He made speculative calls and wrote lots of of letters to obscure addresses in Pakistan, to no avail. He by no means married; with out household round him, he mentioned, “something was always missing so it never felt right”.

It was by probability in 2019 {that a} good friend from the village was despatched a YouTube video from Punjabi Lehar by a relative. In it, an outdated man in his 80s dwelling in Pakistan spoke of looking for the youthful brother he had misplaced after he fled the village of Jagraon throughout partition. After Dhillon was contacted, it was confirmed: this man was Sadiq Khan.

An emotional video name was organized between the 2 brothers, and shortly they had been talking to one another on daily basis. Sikka lastly realized the story of his household; that his father had been murdered in a communal assault and his brother and sister had fled to a border refugee camp the place his sister had died from sickness. Sadiq made it to Pakistan, settled in Faisalabad and had six youngsters and several other grandchildren, however by no means a day glided by when he didn’t consider his misplaced brother.

The brothers had been prevented from assembly for nearly three years due to visa points and the Covid pandemic, however in January, a reunion was lastly organized on the Kartarpur hall, a spot of non secular pilgrimage just lately opened to Indians and Pakistanis. “I felt complete,” Sikka mentioned of the encounter. Both brothers agreed: they’d stayed alive this lengthy in order that they may meet once more.

In April, Sikka was lastly granted a visa to remain in Pakistan for 3 months, and Sadiq then got here again with him to India for 2 months. They hope to see one another once more quickly; Sadiq retains teasing Sikka that if he returns to Pakistan, he’ll lastly discover him a spouse.

“Now I don’t worry about anything,” mentioned Sikka. “I just want to see my brother and stay close to him.” But, Sikka added, he was additionally indignant. “Why did they divide this country, divide my family? There are still so many people who have not found their family or not got the visa to go across the border. I was the lucky one.”