Most prime mathematicians found the topic once they had been younger, typically excelling in worldwide competitions.

By distinction, math was a weak spot for June Huh, who was born in California and grew up in South Korea. “I was pretty good at most subjects except math,” he mentioned. “Math was notably mediocre, on average, meaning on some tests I did reasonably OK But other tests, I nearly failed.”

As a youngster, Dr. Huh needed to be a poet, and he spent a few years after highschool chasing that inventive pursuit. But none of his writings had been ever printed. When he entered Seoul National University, he studied physics and astronomy and regarded a profession as a science journalist.

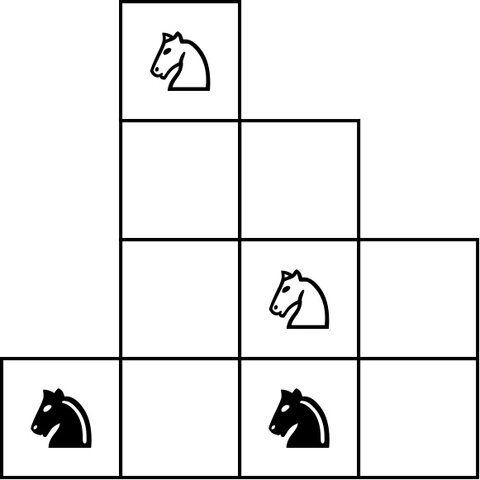

Looking again, he acknowledges flashes of mathematical perception. In center college in the Nineties, he was taking part in a pc sport, “The 11th Hour.” The sport included a puzzle of 4 knights, two black and two white, positioned on a small, oddly formed chess board.

The process was to trade the positions of the black and white knights. He spent greater than per week flailing earlier than he realized the important thing to the answer was to search out which squares the knights might transfer to. The chess puzzle could possibly be recast as a graph the place every knight can transfer to a neighboring unoccupied house, and an answer could possibly be seen extra simply.

Recasting math issues by simplifying them and translating them in a approach that makes an answer extra apparent has been the important thing to many breakthroughs. “The two formulations are logically indistinguishable, but our intuition works in only one of them,” Dr. Huh mentioned.

A Puzzle of Mathematical Thinking

A Puzzle of Mathematical Thinking

Here is the puzzle that June Huh beat:

Goal: Exchange the positions of the black and white knights. →

It was solely in his final 12 months of school, when he was 23, that he found math once more. That 12 months, Heisuke Hironaka, a Japanese mathematician who had received a Fields Medal in 1970, was a visiting professor at Seoul National.

Dr. Hironaka was instructing a category about algebraic geometry, and Dr. Huh, lengthy earlier than receiving a Ph.D., considering he might write an article about Dr. Hironaka, attended. “He’s like a superstar in most of East Asia,” Dr. Huh mentioned of Dr. Hironaka.

Initially, the course attracted greater than 100 college students, Dr. Huh mentioned. But many of the college students shortly discovered that the fabric incomprehensible and dropped the category. Dr. Huh continued.

“After like three lectures, there were like five of us,” he mentioned.

Dr. Huh began getting lunch with Dr. Hironaka to debate math.

“It was mostly him talking to me,” Dr. Huh mentioned, “and my goal was to pretend to understand something and react in the right way so that the conversation kept going. It was a challenging task because I really didn’t know what was going on.”

Dr. Huh graduated and began engaged on a grasp’s diploma with Dr. Hironaka. In 2009, when Dr. Huh utilized to a couple of dozen graduate colleges in the United States to pursue a doctoral diploma.

“I was fairly confident that despite all my failed math courses in my undergrad transcript, I had an enthusiastic letter from a Fields Medalist, so I would be accepted from many, many grad schools.”

All however one rejected him — the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign put him on a ready checklist earlier than lastly accepting him.

“It was a very suspenseful few weeks,” Dr. Huh mentioned.

At Illinois, he began the work that introduced him to prominence in the sector of combinatorics, an space of math that figures out the variety of methods issues might be shuffled. At first look, it appears like taking part in with Tinker Toys.

Consider a triangle, a easy geometric object — what mathematicians name a graph — with three edges and three vertices the place the perimeters meet.

One can then begin asking questions like, given a sure variety of colours, what number of methods are there to paint the vertices the place none might be the identical coloration? The mathematical expression that provides the reply is named a chromatic polynomial.

More complicated chromatic polynomials might be written for extra complicated geometric objects.

Using instruments from his work with Dr. Hironaka, Dr. Huh proved Read’s conjecture, which described the mathematical properties of those chromatic polynomials.

In 2015, Dr. Huh, along with Eric Katz of Ohio State University and Karim Adiprasito of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, proved the Rota Conjecture, which concerned extra summary combinatorial objects often known as matroids as a substitute of triangles and different graphs.

For the matroids, there are one other set of polynomials, which exhibit conduct much like chromatic polynomials.

Their proof pulled in an esoteric piece of algebraic geometry often known as Hodge concept, named after William Vallance Douglas Hodge, a British mathematician.

But what Hodge had developed, “was just one instance of this mysterious, ubiquitous appearance of the same pattern across all of the mathematical disciplines,” Dr. Huh mentioned. “The truth is that we, even the top experts in the field, don’t know what it really is.”