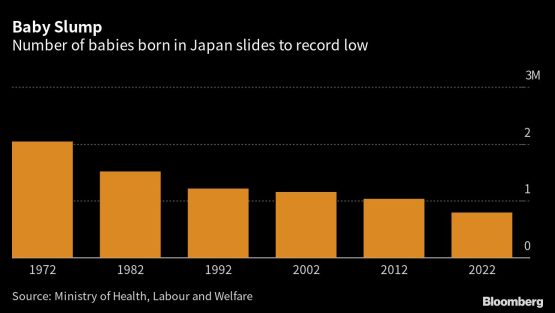

Alarmed by an even faster than expected slide in the number of babies born in Japan last year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is preparing a policy package he says is a last chance to keep society functioning.

Ideas like compulsory paternity leave, canceling student debt for people who have a baby, and ¥10 million ($76,445) payouts for a third child have been thrown around in recent weeks. While some of these are controversial and won’t make it into the final program, Kishida has promised measures “on a different dimension” from previous efforts.

As part of the fresh attempt at tackling the issue, a new agency devoted to children and families is set to open its doors on April 1, and the government will lay out a path to doubling spending on them by June. Kishida has begun floating some of the proposals and more details are expected by the end of the month.

Japan is not alone in its problems —- China’s population has also begun to fall, and South Korea has a lower fertility rate — but it is further along the road, with more than 29% of its people aged 65 or above. Last year marked a record low number of births and a fall of about 0.6% in the total population.

Failure to put the brakes on a slide that will naturally accelerate as the number of women in the fertile age range shrinks won’t just hamper economic growth, but could trigger a collapse in the pension system and leave already-stretched fields like healthcare and defense without sufficient staff, Masako Mori, an adviser to Kishida, warned in March.

The premier on March 17 began to unveil some of his ideas on encouraging people to have babies, saying the country has only a few more years to remedy a “national crisis.”

Kishida is seeking to spread the burden of childcare, in many cases borne almost exclusively by mothers, to fathers and the broader community. He’s introducing new subsidies meant to prompt 85% of fathers to take paternity leave by 2030, compared with the current 14%.

“When we reach the 2030s, the number of young people will plunge at double the current pace,” if trends continue, he said in outlining policies aimed at changing the “structure and consciousness of society.”

Women perform the vast majority of unpaid labor in Japan, at about 3 hours and 45 minutes a day, compared with 40 minutes for men, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Women get less sleep than their counterparts in any other country surveyed. Japan also tops the OECD rankings in terms of the proportion of women who never have children.

“The root of the whole problem is that men and corporations haven’t seen the issue of raising children as their own problem,” said Shiro Yamasaki, an adviser to the cabinet, who was previously a senior official at the Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare. “If that doesn’t change, there will be no solution.”

The recent experience of other countries, however, indicates that more government support and gender equity doesn’t always guarantee more babies. Long-steady fertility rates in Nordic countries, which research has attributed to social policies, have fallen in recent years.

Kishida also plans to tackle low incomes among young people, many of whom are in irregular work that pays poorly and doesn’t come with full social benefits. Salaries for people in their thirties shifted downward over the 20 years from 1997-2017, according to government data.

“Lack of stability is a big issue for men,” Mary Brinton, professor of sociology at Harvard University, said in a March presentation. “Social mores are that men should be able to support a family.”

Concerns about income prospects may not be limited to men — a study by Daiwa Institute of Research found that fertility rates have been rising over the past decade among women in full-time jobs, while they have begun to fall among those who work only part-time, or not at all.

What Bloomberg Economics Says…

“Salary levels for new graduates have hardly changed in 30 years, while the percentage starting off in irregular jobs has been increasing. People can’t be enthusiastic about having many children when they think about education costs.”

— Yuki Masujima, economist

While the number of foreign residents in Japan hit a record of just over 3 million at the end of last year, up more than 11% on the previous year, immigration doesn’t currently look likely to make up the shortfall.

A radical approach could be the only chance of success, given the failure of three decades of more gradual attempts to turn the trend around, like improving access to childcare.

Harvard’s Brinton called in a March presentation for four to six weeks of paternity leave on full pay to be made compulsory. Kazumasa Oguro, a professor at Hosei University and former Finance Ministry official, proposed a cash payment of 10 million yen for couples who have a third child.

“It’s hard to escape the gravitational pull of the falling birthrate with half measures,” Oguro said in an interview.

© 2023 Bloomberg