As the results of the 2024 elections come in and the final results are expected in a few days, a new administration is expected to come into being. However, in a world of competing interests as well as explicit and implicit control and influence the question is “who will in fact be in charge over the next five years?”

This question is made even more relevant with the proliferation of political parties, which results in a glaring fragmentation of the vote. And this further raises the question, are political parties still about serving the people or the interests of those who form them?

Senior researcher, political analyst, lecturer, and nonprofit organisation executive based at Nelson Mandela University in Gqeberha, Dr Ongama Mtimka, argues there is more than meets the eye to the question of who wields power.

“When we analyse who has the power it is a question of evidence of relative autonomy. South African capitalists have been complaining about the labour environment in South Africa; from 1996, with the basic conditions of the Employment Act, Employment Equity Act, from Occupational and Safety Act, they no longer have what they had throughout history – a free reign with labour. They have been the ones who actually fund the politicians,” he argues.

“So, the point I am making is that there is a degree to which there is a symbiosis if you like. It’s not either (or) … power sometimes has got the form of being pro-capital, but when you analyse it’s more nuanced, it’s more fluid,” he adds.

According to Mtimka, there seems to be a compromise in most cases between those who hold political power and those who hold economic power.

“There are decisions which show us that the political have got some form of political autonomy and then there are decisions where you go like you know what business owns, like in mining for instance. Mining is a typical example where that issue is being negotiated through the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act, where it’s not the ideal position mining capital would want, nor is it a position that the rest of the society would want. It’s a compromise.”

Lecturer, researcher and political analyst, Dr Dale Mckinley has described the Dr Mtimka scenario as one that requires “a strong, capable state” accusing the ANC of having failed to live up to that expectation.

“Let me give you an example. We have the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, we have all these great legislations, but the labour inspectorate in this country has less than 200 inspectors to go around over 100 000 major businesses, which means employers basically do what they want to do.

Pulling no punches, Professor Ntsikelelo Breakfast, who leads the Center for Security, Peace and Conflict Resolution at Nelson Mandela University, has described the idea of state capture as being “under-theorised”, saying the state is captured by capital.

“…because the state is an expression of class antagonism. So, why talk about state capture? The dominant narrative is the one that is pushed by the liberals that state capture only happens when you have a shadow state. I think there is more to it than meets the eye.”

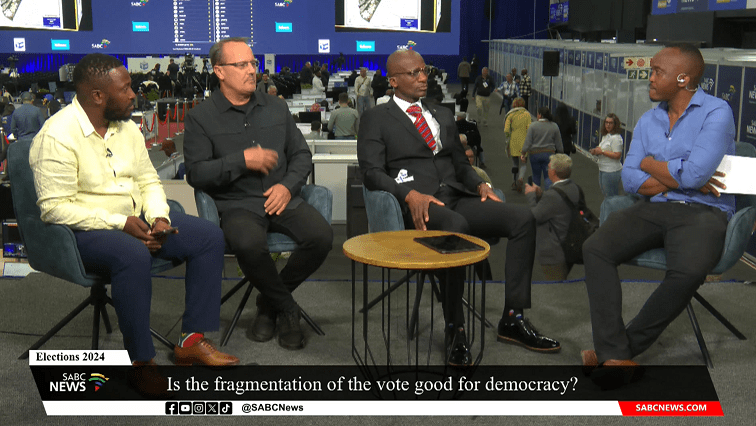

Full engagement below | Is the fragmentation of the vote good for democracy?