Detroit is poised to mark the 10th anniversary of its historic bankruptcy by tapping the municipal bond market for $100 million of financing, most of which will go toward its program of reviving blighted neighbourhoods.

The debt is scheduled to price on Tuesday, 10 years to the day after Michigan’s biggest city, groaning under debt and pension obligations and hobbled by decades of population loss, filed what was at the time the nation’s largest municipal bankruptcy.

Today, the city of about 620 000 is on the cusp of investment grade. S&P Global Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service both raised its credit rating in April to the highest level since 2009, with the latter citing “robust revenue growth” and an influx of federal pandemic aid.

Mayor Mike Duggan said the city’s rebirth is well underway. He pointed to falling joblessness, surging home prices, downtown office buildings that are solidly occupied and an entertainment district that’s luring new residents and suburbanites, with more developments on the way.

“Downtown is a neighbourhood now,” he said in an interview. “The downtown I knew, everyone drove in in the morning and everybody drove out at 5. Now it’s vibrant.”

The $18 billion Chapter 9 filing in 2013 ignited public protests and put key institutions — including the prized collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts — at risk. Both the size and the scope of the restructuring made the case notable: Kevyn Orr, the city’s emergency financial manager, cut $7 billion in debt through agreements with pension systems, labour unions, hedge funds and bond insurers, and hundreds of millions in funding flowed in from foundations and the state to buoy its retirement funds. Detroit exited bankruptcy in December 2014.

‘Stigma is gone’

Demand for the new securities should be solid, given the fiscal strides the city has made, investors say.

“It appears that the stigma is gone,” said Larry Bellinger, director for the municipal credit research group at AllianceBernstein. “It’s certainly a strong credit and I think it signals, at least to me, that the market is more comfortable with bankruptcy in the municipal market.”

Detroit points to eight years of balanced budgets, the lowest poverty rate in 14 years and dropping unemployment, along with beefed-up budget reserves and higher-than-expected tax collections. Blight remediation has helped lift median home values by 17% over the 2019-2021 fiscal years, an investor presentation shows.

The city’s “finances continue to strengthen and improve with each new year,” Stephanie Davis, a spokesperson for the office of Chief Financial Officer Jay Rising, said via email. “All major revenues have surpassed pre-pandemic levels and are projected to continue growing.”

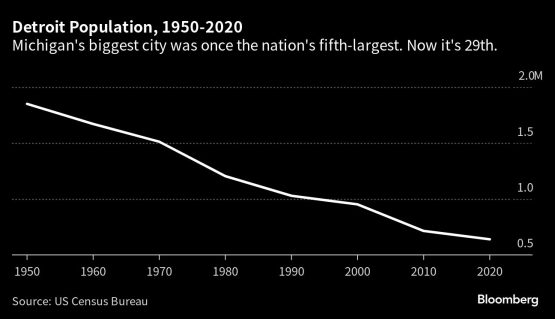

Rising’s office says the population has stabilised after falling from a peak of 1.85 million in 1950 as US carmakers shifted production out of town.

The city has designated $75 million of this month’s debt offering as “social bonds” as proceeds will be used to demolish and renovate vacant and decayed homes. The remaining $25 million will fund transportation and recreation programs.

Detroit returned to the bond market in 2018 with a $135 million sale, its first time since the bankruptcy to issue bonds backed only by its promise to repay. The city followed with an $80 million sale in 2020 and $175 million in 2021. The last issue sparked strong demand and repriced at a tighter spread, with a bond due in 2036 with a 5% coupon yielding 2.22%, or 122 basis points over the BVAL benchmark, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“I’d have to imagine wherever fair value is these days, they will get that or better,” said Jason Appleson, head of municipal bonds at PGIM Fixed Income. “The market has been starved for high-yield paper. Detroit is a recognisable name, it’s got an improving trajectory, and frankly, it’s a small deal.”

The latest offering continues a program to spruce up neighbourhoods degraded by population loss and poverty. In 2020, more than 70% of Detroit voters approved a plan to issue $250 million in debt to renovate and demolish blighted properties, according to an investor presentation for this deal.

The city says it’s renovated or demolished 85% of its blighted and vacant buildings since 2014, with 24 000 taken down and 16 000 sold. About 7 000 vacant structures remain, of which 2 500 are targeted for demolition using bond proceeds, with the rest to be sold, stabilized or removed through other financing.

The city still faces “elevated social risks,” S&P analysts Randy Layman and Jane Ridley wrote in an April report.

The more than 30% of non-residents working remotely, as well as poverty levels that remain high by national standards, uncertainty about economic growth and looming pension costs remain concerns, they said. The city must resume pension contributions next year and in 2017 created a trust fund to put aside that cash.

While well-managed, Detroit is reliant on income taxes and gambling-related levies, making its revenue more volatile, Layman said in an interview this week.

“The city has really done a lot to tackle what it can control,” said Stephanie Leiser, a public-policy lecturer at the University of Michigan and head of the school’s Michigan Local Government Fiscal Health Project.

But it’s continued to grapple with efforts to boost growth and the loss of what she called the prime working-age population as families move out seeking better schools and services.

“They’re doing what they can,” Leiser said. “But there’s a way to go.”

© 2023 Bloomberg