‘Tis the season. For year-ahead outlooks, that is. It is the time of year when banks, fund managers and the investment commentariat at large gaze into crystal balls and prophesise about the planet’s next rotation around the sun.

This week’s note will do the same, while next week we will attempt to look even deeper into the future.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

Read: Kganyago sees 2024 elections among top risks for South Africa

Before we get there, two obvious caveats. Firstly, the future is unpredictable. If you didn’t know that before Covid, you certainly do now. Therefore, rather than obsess over exactly what is coming our way, we should focus on ensuring that our portfolios are robust across a range of different scenarios.

We should also spend a lot more time worrying about those things others are not worried about, since these are the events or outcomes that are not fully discounted by markets. Secondly, months and years are quite arbitrary distinctions in a world where markets trade continuously round the clock and one day bleeds into the next.

Still, the human brain likes compartmentalising and putting things into discrete boxes. So here goes.

The big surprises this year – again illustrating the folly of forecasting – were the unexpected resilience of the US economy despite much higher interest rates and the unexpected weakness of the Chinese economy despite ending lockdowns.

These are also areas to think about as we head into 2024.

US exceptionalism

At the start of the year, the US economy was widely expected to fall into recession. That didn’t happen as consumers kept spending, supported by ample savings and a healthy labour market.

For the US economy, indeed the global economy, the strength of the American consumer is key. They also benefitted from the rise in real income as inflation fell during 2023, buoyed by solid wage gains.

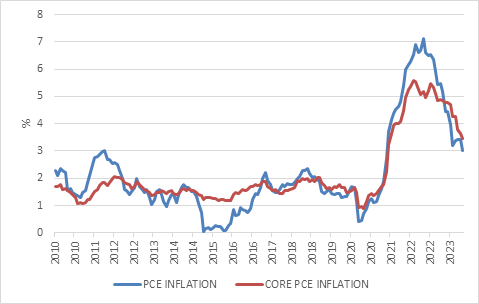

US personal consumption inflation rates

Source: LSEG Datastream

The impact of higher rates on consumer finances has been limited in aggregate since most mortgages have fixed rates and households strengthened their balance sheets over the previous decade (which is a fancy way of saying debt declined and asset values rose). But for many individual consumers, it has been tough going to get affordable finance to buy a house or car. At the margin, therefore, consumer spending is cooling.

The big question for next year is whether real income growth stabilises at a lower but comfortable pace, or whether it slows meaningfully with a rise in unemployment. On balance, it looks to be the former. The rate of job creation is cooling, but there is no sign yet of a major crack in the labour market.

Inflation has fallen a lot in the US and other developed countries. It is not back to target yet but moving in the right direction.

There are still items that can prove to be sticky, especially if consumer spending remains robust, and of course supply shocks are by nature unpredictable. But broadly speaking, it is hard to imagine a strong upturn in inflation next year unless there is an unlikely acceleration in economic growth, and labour markets tighten.

Read: Is a seemingly resilient America starting to show signs of cracking?

This in turn suggests the US Federal Reserve is done hiking and that the next move is lower. It will only cut rates early and aggressively if recession risk rises materially. If the economy chugs along, it will probably err on the side of keeping rates near current levels until the second half of the year to ensure inflation falls as planned.

Therefore, investors betting on falling rates need to be careful what they wish for. Rates can fall for good reasons (inflation under control) or bad ones (recession).

The outlook for US economic growth, inflation and interest rates is critical for global markets, much more so than developments in any other single country or region. If you could hope to correctly predict the outcome in one country, it will be the US.

China concerns

China will be second on the list, but it is of lesser importance. Though it is the world’s second largest economy, it is much less integrated into global capital markets and exerts less influence on them.

The notable exception, of course, is in commodity markets where China is generally the biggest single source of demand (though the US is the biggest consumer and producer of crude oil).

China’s problems are mostly long-term in nature. It has unfavourable demographics, too much debt and the overhang of massive overbuilding in property and infrastructure.

However, it is also a tightly controlled system where losses can be distributed in an orderly fashion. Monetary, fiscal and regulatory stimulus efforts are likely to stabilise economic growth as we head into next year, avoiding the immediate risk of a decline into Japanese-style deflation (it should be noted that Japan itself might finally have exited its own deflationary regime, and the Bank of Japan might buck the trend of easing central banks next year by normalising its ultra-loose policy stance).

These measures might help raise the confidence of depressed Chinese consumers somewhat. But despite short-term stabilisation, it remains highly likely that China’s economic growth rate will slow in the coming years.

China consumer confidence

Source: LSEG Datastream

A better near-term outlook in China can also be positive for emerging markets more broadly speaking, as will a stabilisation in US-China relations.

The moment has passed where the two superpowers can be friends, but there is some hope that competition will not descend into outright conflict.

Read: Pandas, Pegasus or the Chimera: Which will symbolise US-China relations?

The US election will be crucial. At this stage, it looks like we are heading for a rerun of the 2020 presidential election, except with Joe Biden as the incumbent and Donald Trump as the challenger.

While Biden is not a China dove, Trump is an outright hawk.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

In a tight election, it isn’t a given that either party will win a clean sweep, however. If the White House and Congress are controlled by different parties, not much will change in terms of domestic policy. In the realm of international affairs, however, the president has more room to act alone. Diplomats across the world will watch the election with trepidation.

To the local polls

South Africa will also go to the polls next year, and for the first time since 1994, an ANC majority cannot be taken for granted. However, the most likely outcome is one where the ANC governs in a coalition with one or more small parties.

This implies broad policy continuity, including a gradual reforming of state-owned companies and the public sector in general. This will bear fruit eventually, but will be immensely frustrating in the meantime.

Listen: Political scenarios SA could see post 2024 elections

The current crisis at the ports is a case in point. The government has adopted a strategy to bring in private players to partner with Transnet in running port and rail operations. This is a decisive shift away from the mentality that the state must own and manage these network industries. However, implementation will take time. The same is true on the electricity side, though the process is further down the track.

A few years from now, the electricity and logistics sectors will look very different, with more private players and less reliance on Eskom and Transnet. But in 2024, the failings of these companies will cap the economy’s real growth rate somewhere between 1% and 2%.

Indeed, if there is going to be an upside surprise to economic growth, it will come from accelerated private investment to bypass their inefficiencies.

The biggest component (60%) of economic activity remains household spending. This follows growth in real household income, which is likely to be around 1% next year due to the continued gradual post-pandemic recovery in employment, modest wage growth and somewhat lower inflation.

This is not exciting, but it means overall economic growth should be better than in 2023 and certainly, the economy is not falling off a cliff as it is often described as doing.

National budget

The tabling of the 2024 Budget will be an important event. The country’s sub-par growth rate is the main reason the government has been unable to close the budget deficit, the difference between government spending and tax revenue that is funded through borrowing.

But there is also no denying the fact that much government spending is misplaced, duplicated, or unnecessary.

And where it is necessary, it is often inefficient. Promises of an overhaul of government spending were made in the mid-term budget policy statement, and also previously by President Cyril Ramaphosa. It is now time to deliver. The alternative of slicing away at departmental budgets every year is becoming counterproductive as the good is often cut with the bad.

SA bond yields

Source: LSEG Datastream

The local bond market will continue to largely be driven by fiscal risks, and local bonds will not rerate relative to peers unless there is a vast improvement in the fiscal outlook. However, the short end of the bond curve is more sensitive to monetary policy and is starting to price rate cuts.

How fast the SA Reserve Bank cuts rates will depend greatly on international factors, specifically what the Fed is expected to do.

Domestic inflation should hover around the 5% mark during 2024. Some upside pressure is likely due to Transnet and Eskom inefficiencies. But there is also downward pressure on prices from lacklustre consumer demand. The exchange rate and global energy prices are short-term swing factors.

Speaking of the rand, its trajectory will depend greatly on what the dollar does. The rand has lost almost 30% against the dollar in the past 18 months. It typically bounces back from such a blowout.

In practice, this means the dollar must weaken, which in turn implies that the US growth outperformance should fade and that the interest rate gap between the Fed and other central banks closes. This is possible but not very likely, and therefore, while the dollar’s bull market is probably over, it is not yet time to call a bear market.

12-month forward price-earnings ratios

Source: LSEG Datastream

All in all, as the title of the piece suggests, there is reason to be a bit more optimistic next year from a macro perspective as a soft landing is a more likely outcome than a few months ago. But this view is also now largely discounted, as November’s sizzling rally in bonds and equities indicates. There is room for disappointment and therefore 2024 is not the year where diversification goes out the window.

What the inflation and labour market trends and rhetoric from central banks suggest is that there is no reason to hike economies into oblivion. Rates can fall next year, equities can rerate and it is clearly good for bonds. The risk now shifts to earnings. The consensus view is that company profits will post solid growth next year. If economies slow more than expected, this rosy outlook will be challenged.

Moreover, we also need to consider where rerating can take place. It is hard to see a meaningful rerating for the ‘Magnificent Seven’ US technology giants, since they are already pricey.

Other unloved areas of the market can do better, that includes South African equities. However, remember that the stock market is never a one-year investment, since anything can happen over the next 12, 24, or even 36 months. If you are going to deploy money into equities, focus on getting valuations on your side and be prepared to commit for several years.

Fortunately, the former part of that equation holds; equity valuations are cheap to fair outside US tech as the final chart above shows. As for the latter part of the equation, that is up to you.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth.