This week’s annual summit of the Brics nations – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – is notable for several reasons, not least because South Africa is the host this year.

It is the first in-person summit of heads of state since the pandemic, but Russian President Vladimir Putin will not attend due to the International Criminal Court indictment against him.

Read:

Russia’s growing global isolation and escalating tensions between China and the US also mean the summit has received more media attention than previously.

It is worth remembering that this rather awkward grouping of very different countries started out in a Goldman Sachs research paper 22 years ago, when then-chief economist Jim O’Neill argued that the ongoing economic rise of Brazil, Russia, India, and China would necessitate a reordering of global governance institutions.

O’Neill wasn’t wrong, but coming soon after the dotcom crash, the Bric concept quickly became a marketing fad as the hot new thing in investments. This idea gathered further momentum when these countries emerged from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis in better shape than the West.

In 2009, the leaders of the four countries met to turn the acronym into a political club. South Africa was later invited to join, and formally became a member in 2011.

Brics is however still more form than substance.

It remains an informal arrangement for now, lacking a founding charter, and importantly as we’ll see below, any kind of free trade arrangement.

The one tangible creation of Brics is the New Development Bank, set up as an alternative to the World Bank and other Western-led development institutions, but it remains small compared to them.

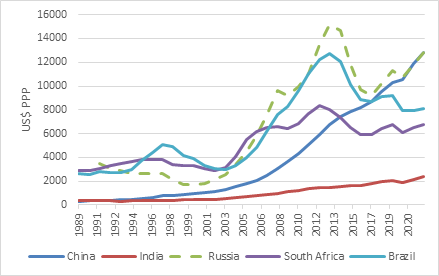

Far from collectively being the countries of the future, the Brics have had divergent performances since the club was formed in 2009.

The chart below shows that China’s spectacular gains in real per capita income continued, but as we now know, serious imbalances built up over this period, including a property bubble and associated rapid rise in private debt that is likely to create an overhang constraining growth in the years ahead. China’s declining population, like Russia’s, is also a structural headwind.

India has also managed sustained improvements in living standards from very low levels of per capita income. With its large and relatively young population and high savings rate, India can continue to grow rapidly in the years ahead with the right government policies.

Real income per capita

Source: World Bank

Russian national wealth rises and falls with energy prices, and on the surface looks strong. But being cut off from the rest of world will do serious long-term economic damage. In the past week, its central bank was forced to hike rates in an unsuccessful attempt to halt a sharp decline in the rouble caused by the demands of running a war economy. While Russia has found new customers for its oil and gas in countries like China and India, it is selling at a discount to them. Increasingly, it looks like Russia is locking itself into a subordinated economic relationship with China.

South Africa and Brazil have followed very similar patterns, since they have similar unequal, unbalanced and commodity-intensive economies.

Both countries enjoyed rapid growth in per-person incomes during the pre-2008 commodity boom, but have stagnated since. In the absence of politically difficult structural economic reforms, history suggests that we’ll have to wait for the next commodity boom to see another jump in living standards in these two countries.

South Africa is a tiny economy compared to the other four, since its population of 60 million is half that of Russia’s and slightly more than a quarter of Brazil’s. China and India are billion-plus people behemoths.

But China is the biggest economy by far, bigger than the other members combined. Therefore, while Brics commentary will note that the club is responsible for a quarter of global output, it is clear who does the heavy lifting and carries the clout.

Realignment

While there is much talk of a new geopolitical alignment of developing countries (the ‘Global South’), it should not be assumed that all developing countries are on the same page. While there is a common weariness of perceived Western hypocrisy, there isn’t necessarily much else tying countries together, within Brics and the broader collection of developing economies.

For instance, perhaps the oddest feature of Brics is that India and China have fought wars over disputed border areas, most recently coming to blows in 2021.

Moreover, while China, India and South Africa abstained in recent United Nations votes to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Brazil supported the resolution. Of the other developing countries apparently keen to join Brics, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have also voted to support the resolution, while Iran abstained.

The topic of Chinese expansionism is such a sore point in South-East Asia that Vietnam banned the Barbie movie for showing a map with the “nine dash line” of China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Now, the West is also not united on all issues. Most of Europe was fiercely opposed to America’s invasion of Iraq in 2003, for instance, while US President Donald Trump in turn made it clear that he saw Europeans as freeloading on America’s defence spending (which, at almost $900 billion per year, is still more than all the Brics combined, according to the Lowy Institute). But on key issues and values, there is much more holding the West together than pulling it apart.

The point then is not that we are seeing the emergence of a powerful united bloc as a counter to the West, but rather the continued emergence of a multipolar world.

Few benefits

How has South Africa benefitted from Brics membership beyond the prestige of belonging to a club of much bigger economies?

In answering that question, we should remember former British prime minister Lord Palmerston’s injunction – “countries have not permanent friends, only permanent interests”.

South African export destinations

Source: International Monetary Fund

From a trade point of view, the other Bric countries, led by China, are a very important export destination.

But as the above chart shows, the dollar value of exports to the other Brics nations has barely grown since South Africa joined the group in 2011.

There is still a massive opportunity to grow and diversify exports to these countries, particularly India and China, and to attract tourists to our shores.

But there is still no sign of a Brics free trade agreement to facilitate this.

Moreover, it would be unwise to seek growing trade with Brics at the expense of existing relationships with Western democracies. The ongoing Agoa [African Growth and Opportunity Act] negotiations with the US will test our diplomatic nous in charting a course between East and West.

The West, shown on the chart as the European Union, the UK and the US, collectively remains our biggest export market, dominated by exports of raw materials and dependent on their price shifts.

Finally, and often forgotten, is that South Africa’s natural export market remains its neighbours. The nascent African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement holds much promise, but substantial investment in institutions and infrastructure is needed to fulfil it.

The picture on foreign direct investment (FDI) is similar. A study by Unctad, the United Nations trade body, shows that the stock from other Brics members into South Africa declined somewhat from 2010 to 2020, from $7.2 billion to $6.9 billion, and stands at 5% of the total stock of FDI. Of course, we don’t know if FDI from the other four would have been even lower if we didn’t join the club.

Either way, the biggest source of FDI for South Africa by far remains the US and Europe.

Would a Brics common currency facilitate the needed growth in trade? It is not an idea even worth considering.

A common currency requires something approximating a common economy, with free movement of goods, services, and capital as is the case in Europe. Clearly, we’re still dealing with five very different economies in the Brics, never mind the vast geographical distances between them.

And even though the European common currency (the euro) has greatly facilitated the ease of trade, commerce and travel on the continent, it hasn’t been without problems as we saw during the fiscal crisis of 2011-2012.

The eurozone has a single central bank but not a single fiscal policy stance, and this almost tore the entire project apart and remains a source of risk.

What we might see instead is that a greater portion of trade between Brics countries moves to being invoiced and settled in local currencies instead of US dollars, an idea with substantial political backing. But there are practical reasons for the dollar’s dominance, so this will likely be a very gradual process.

The market has lost interest

Finally, since the Brics concept started life in the world of fund management, we might ask what the market is telling us about these countries.

In terms of stock market performance, the big winner since the formation of Brics has been India. The optimism around the country’s economic future reflects in its stock market, since valuations have increased.

Forward price-earnings ratios

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

At the opposite extreme is Russia. It has completely dropped off the radar screens of global investors following the war, and leading index providers such as MSCI have excluded the country’s shares from international benchmarks. Even before the invasion, Russian equities carried a deep governance discount, persistently trading on low single-digit price-earnings (PE) ratios.

Despite the country’s growing economic might, China’s equity performance has been tepid, depending on the benchmark. Recently, investors have substantially cut their expectations for the future, and the market trades on a muted PE ratio.

Brazil and South Africa’s equity markets similarly discount much pessimism and currently trade at levels below the average of the past decade or so.

In other words, if there is a Brics story, the equity market is not buying it. There is excitement about India, pessimism about Brazil, China and South Africa, and outright revulsion at Russia.

10-year local currency government bond yields

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

In terms of bonds, there is also no sign of convergence.

Brazil’s local currency 10-year government bond yield has endured wild swings, while South Africa’s has increased since 2010. In both cases, it is largely because of worsening fiscal dynamics.

Read: ‘Brics bank’ issues first South African rand bonds

While India has a higher government debt-to-GDP ratio at 80%, its rate of economic growth is also higher. It can therefore grow into this debt, and clearly the bond market is not too worried.

As an international pariah, it is hard to draw much signal from the Russian bond market nowadays, as foreigners pulled out en masse in 2022. Rising yields do suggest domestic Russian investors are worried.

Going in the opposite direction, China’s bond yields have been grinding lower, a sign of the bond market expecting lower inflation and interest rates in the years ahead.

Read: Red dragon blues

This would be good news in most countries, but not China, where the risk of Japanese-style deflation has increased.

Mind the hype

In a nutshell, the Brics concept is one that has always been surrounded by fanfare, initially because of the expected superior growth rates of these countries, and more recently because of growing geopolitical tensions.

As a rule of thumb, investors should be sceptical whenever there is such hype. Brics is not nearly as coherent a group as is often imagined, but these are still important countries, each interesting in its own right with investment opportunities and risk.

The key factor, as always, is to take a balanced approach to making investment decisions, focus on valuations, and apply the necessary patience.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth.