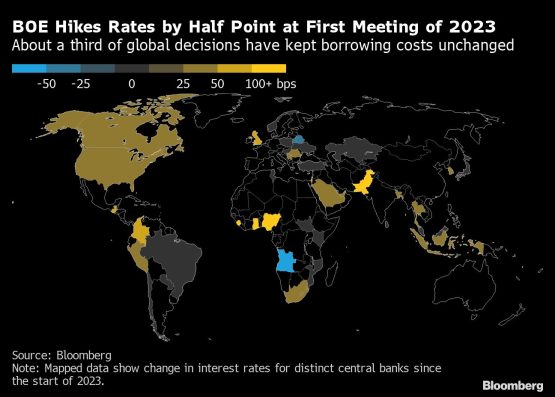

The Bank of England raised interest rates a half point, saying more increases will be needed if signs of an inflationary spiral persist.

Seven of the UK central bank’s nine-member Monetary Policy Committee endorsed the hike to 4%, while two voted for no change. The majority said strong pay growth and an ongoing shortage of workers were feeding price pressures in the economy.

The decision marked the 10th increase since the BOE started hiking in December 2021, bringing the key rate to its highest since 2008.

UK bonds trimmed earlier gains after the decision, with the yield on 10-year gilts down seven basis points at 3.23%. The pound trimmed earlier losses against the US dollar to trade around $1.2345. Money market bets imply a peak rate of 4.5% by the middle of the year, compared with around 4.4% prior to the rate decision.

Officials led by Governor Andrew Bailey estimated the economy is already in recession but that the downturn will be shorter and shallower than they had projected in November. The risks to inflation remain “skewed significantly to the upside.” The committee pointed to record pay settlements this year.

The BOE estimated a decline of almost 1% in gross domestic product across five quarters. That will pose a challenge to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government, which must call an election by the start of 2025. The economy will not recover to pre-pandemic levels of output until at least 2026 and 500,000 more workers will lose their jobs, the BOE predicts.

The contraction the BOE estimated is still smaller than the 2.9% fall over eight quarters predicted in November.

Despite the dismal backdrop, the BOE appeared to endorse the market view that rates will peak at around 4.5% in the coming months. The panel warned that “if there were to be evidence of more persistent pressure, then further tightening in monetary policy would be required.”

The market path currently anticipates rate cuts next year. In a sign that the end of the rate-rise cycle may be nearing, the BOE dropped its guidance that it would respond “forcefully” if necessary.

The range of views on the MPC reflected the challenge of fighting inflation, which is lingering near a 40-year high, and coping with a difficult economic outlook.

Silvana Tenreyro and Swati Dhingra voted to leave rates unchanged, saying the impact of past increases has yet to take full effect. Catherine Mann, who voted for a 75 basis-point increase last time, joined Bailey and the majority of MPC members in calling for 50 basis points.

The BOE slashed its projection for the supply potential of the economy, noting Britain’s exit from the European Union was weighing on trade and that many workers have dropped out of the labor force.

In two years’ time on the market path for rates, consumer price inflation is below the 2% target. But policymakers cautioned against taking the forecast too definitively. “An inflation forecast that took into account these upside risks was judged to be much closer to the 2% target,” the committee said.

The BOE slashed its estimate of potential output, the economy’s growth speed limit, to 0.7% for the next three years – down from 0.9% in November and from 1.5% at its last “supply stock take” 15 months ago. Before the financial crisis, the trend rate was 2.5%, and in the decade to the pandemic was around 1.5%.

The bank blamed a constellation of economic shocks, including Brexit, the pandemic and the energy prices. Specifically, it noted a shortage of workers, soft business investment and weak productivity.

The economic cost of Brexit hasn’t changed, but the BOE now believes more of the impact will come upfront. It reiterated that “the level of productivity would be around 3.25% lower in the long run” because the UK pulled out of the EU free-trade area.

© 2023 Bloomberg