It was a tough week for England – a narrow defeat against arch enemy Australia in the first The Ashes 2023 test was followed by a gloomy inflation report which showed UK price pressures remaining uncomfortably high.

In response, the Bank of England announced a bigger than expected interest rate hike with the warning that more was possibly to come.

Rounding off the bad news, the latest data on government borrowing puts the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 100% for the first time since 1961, when it was still paying off World War II debt.

We’ll leave cricket commentary to the relevant experts, but when it comes to inflation and rates, there are several important points to highlight.

London, we have a problem

The UK has a serious inflation problem. With the great energy and food price shock of 2022 starting to roll out of the year-on-year numbers, one cannot blame Russia anymore.

Headline inflation was unchanged at 8.7% year-on-year in May. To avoid 2022 confusing things, we can look at the three-month-on-three-month annualised rate of change. This was 11%.

Read: UK inflation exceeds all estimates as core prices surge

Even worse, we can completely exclude the impact of volatile food and fuel prices, a measure known as core inflation. This increased to 7% year-on-year and to 12% on a three-month annualised basis.

While core inflation has been gradually declining in other developed economies, it is still going the wrong direction in the UK.

As in other parts of the developed world, the UK has a labour shortage and unemployment is low despite tough economic conditions.

This is one of the reasons why so many South Africans seem to be moving there recently. However, immigration from the European Union continues to decline because of Brexit, and this is adding to the lack of workers. It is notable that Brexit regret – Bregret – is also running high as the decision to leave the European Union starts to impact daily life.

Read: UK recession risks grow with record deficit and output slump

A recent YouGov poll showed that 62% of voters felt leaving the EU had been “more of a failure than a success”, with just 9% saying it had been a “success”. While South Africa remains a world champion at scoring own goals, the country where football originated has given us a run for our money in recent years.

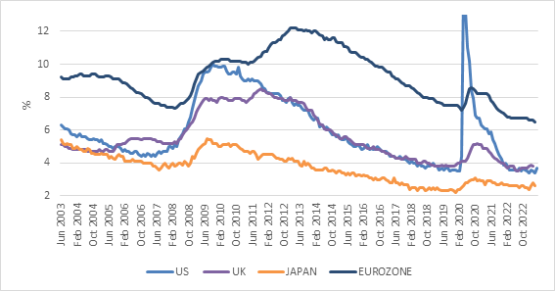

Unemployment rates in developed countries

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

As a result, wage growth is running at 7.5% in Britain, compared to around 5% to 6% in the US and 4% to 5% in the Eurozone.

While the average worker is not being adequately compensated for inflation – they are getting poorer in real terms – their incomes are rising at a pace that can sustain inflation well above the Bank of England’s 2% target.

There is a real risk of a wage-price spiral developing where wages rise to catch up with inflation, while firms push up prices to compensate for wage costs to maintain profit margins.

This is particularly possible in service industries, where wages make up a larger portion of total costs.

You can’t blame workers for wanting to maintain real wages and you cannot blame companies for wanting to grow profits. Market forces normally keep these pressures in check.

If there is sufficient competition between firms, and if consumers refuse to pay up, companies will moderate price increases. They might even cut prices. Sometimes, however, external events give companies cover to raise prices aggressively because they can blame a war, or a weak currency or load shedding, knowing that other firms are likely to do the same and unlikely to undercut them. Consumers focus on the external shock and don’t push back too much.

Read: Europe’s economic engine is breaking down

In the end, then, the only way to short circuit this behaviour is to slow demand in the economy such that workers don’t bid up wages for fear of job losses and firms don’t raise prices for fear of losing customers.

That is where central banks come in, using what is admittedly a very blunt instrument, namely interest rate increases.

Bank of England policy interest rate

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

The Bank of England hiked its policy rate by 50 basis points to 5%, the twelfth consecutive increase since starting at 0.1% in December 2022. It is now the highest it has been since 2008 but is clearly still deeply negative in real terms (after inflation). As a crude rule of thumb, it is only when interest rates are positive in real terms that you really start squeezing the economy. One person’s inflation is another’s income, so high inflation makes servicing debt easier if rates are negative in real terms when looking at the economy as a whole.

Nonetheless, there are always parts of the economy that are squeezed by even modest rate increases. This usually includes the housing sector, which in the UK is a national obsession on par with football and celebrity culture.

First fixed, then floating

UK mortgage rates are typically fixed for two to five years before they float with prevailing interest rates. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, around a quarter of UK mortgages will reset to much higher rates this year, resulting in average monthly payments rising by £280 from £670. This near doubling of mortgage costs for a substantial portion of homeowners will result in a large one-off hit to income after tax mortgage payments of around 10%.

This is where countries with long-term fixed mortgage rates have an advantage, notably the US. This is one of the reasons why the US consumer has remained resilient in the face of a doubling in mortgage rates since most are unaffected. The surge in mortgage rates had the unexpected effect of virtually freezing the market for existing homes, however. Homeowners are extremely reluctant to give up a sub-3% mortgage rate and take out a new mortgage at 7%.

This is forcing prospective buyers into the smaller market for new homes, where there is more inventory and flexibility of supply. Developers are also pricing new homes more realistically. As a result, there is a resurgence in building activity, and the modest decline in house prices to date might not last.

One implication is that the timing of a US recession, often caused by the cyclical and interest-rate sensitive sectors like housing, is pushed out. The other side of this coin is that the Federal Reserve might be forced to raise rates further and keep them at higher levels. In testimony to United States Congress last week, US Federal Bank chair Jerome Powell said more rate hikes are likely.

South African inflation

Source: Stats SA

Local rates squeeze

In South Africa, homeowners also face a squeeze. The monthly repayment on a R1 million bond based on prime plus 1% has jumped from around R8 300 to R11 500. This is almost 40% more.

Read: SA’s middle class is broke

Unlike in the UK, this increase is gradual since the prime rate rises automatically in line with the repo rate. There is no one-off jump and homeowners have time to adjust. The net result is very similar, however. There is less money at the end of each month to spend on discretionary items.

The silver lining is that inflation is subsiding, and this will take pressure off interest rates.

Consumer inflation dipped to 6.3% year-on-year in May from 6.8% in April. Food inflation has finally turned the corner, falling from 14% to 12% year-on-year. This doesn’t mean consumer food prices are lower, just that they increased at a slower pace. As an aside, UK food inflation was 18% in May, so it is not only a South African issue. German food inflation was 14%.

Fuel inflation declines

Petrol inflation declined to 3.5% in May but will turn negative on a year-on-year basis in June, pulling headline inflation down lower. The rand oil price is currently 20% lower than a year ago, and the recent firming in the rand means there might be a petrol price cut early next month.

Read: Consumers expect more hardship

Core inflation is more relevant to the South African Reserve Bank (Sarb), since it reflects how companies are passing on input costs to consumers, bearing in mind that these days fuel is not just used for transport but also for running generators. It was slightly lower at 5.1% year-on-year in May, a comforting decline. That core inflation is muted by current international standards pointing to the lack of domestic demand.

When it comes to interest rates, the Sarb’s Monetary Policy Committee will want to see further declines in June’s inflation data at its next meeting in July, as well as continued stability in the rand.

At the May meeting, an exchange rate of R18.60 per dollar was assumed in its inflation forecasts. The rand is currently a bit weaker than that. Finally, to the extent that load shedding results in higher prices, it will also want to see the recent reprieve continue. Market expectations for future rate hikes locally have fallen considerably, unlike in the UK.

What does it mean?

Finally, a few thoughts on investment implications. Firstly, last year, inflation and interest rates moved in the same direction in all developed countries except Japan. Now the cycles of individual economies are starting to move in different directions and at different speeds.

One area where this is felt directly is in foreign exchange markets. The pound has gained 5% against the dollar in the past six months.

Read:

Secondly, investors simply cannot ignore higher interest rates across the world. We are in a very different regime compared to the pre-Covid-19 zero interest rate environment, unlikely to return there any time soon if at all.

Thirdly, much like South Africa, the UK’s near-term economic outlook is gloomy. And much like South Africa, UK equities have discounted this negativity, trading on 11 times forward earnings (nine times for SA), and a dividend yield of 4%.

The similarities don’t end there. The London Stock Exchange, like the JSE, is home to global companies that are not dependent on the UK economy. Therefore, drawing a straight line from the UK economy to the FTSE is as problematic as doing the same from the SA economy to the JSE.

Interestingly, the FTSE 100 and FTSE/JSE All Share Index have delivered virtually the same return over the past ten years when measured in the same currency. Both are ‘value’ markets, while ‘growth’ has been the dominant performer of the past decade, led by US tech.

FTSE 100 and FTSE/JSE All Share in pounds

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

There is also a real concern in the UK that leading companies no longer want to list on the London Stock Exchange, preferring to move their listings to America to access a broader investor base and get a better rating, much like AngloGold did when it moved its listing from the JSE to New York.

Read: Tough times ahead as South Africans face financial crises

Finally, notwithstanding the above, the return outlook for UK investors has improved. This is one of the ironies of investing, namely that potential future returns tend to increase as uncertainty rises and past returns fall.

Equities are attractively priced compared to history while bond yields are at the highest levels in 15 years. They are not yet positive in real terms, however, unlike South Africa, where long bond yields are twice the core inflation rate. The key factor will therefore be whether the Bank of England gets inflation under control without having to pummel the economy like Usman Khawaja did to the English bowling line-up.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth.