After more than a decade of overbuilding and overborrowing, the moment of reckoning is here for China’s real estate market. Sales are down, prices are down, construction is down, developers are defaulting, and contagion is spreading to the shadow banking sector.

A Goldilocks outcome remains possible. Sales have fallen so far that there’s scope for more stimulus to boost demand without reinflating the speculative bubble. If that doesn’t happen and the sector continues to spiral down, a massive funding gap for developers means there’s the real possibility of a financial crisis.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

For China, the difference between those two outcomes is 5% or 0% gross domestic product growth in 2024. Bloomberg Economics’ base case is at the top end of that range. If we’re wrong, global spillovers from the crash scenario would be enough to tip the US and other major economies into recession.

Haunted by ghost towns

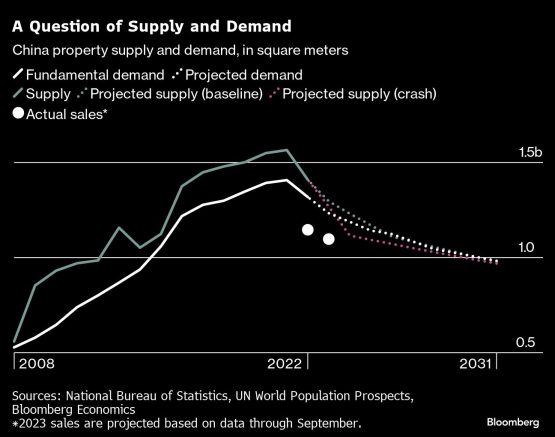

The fundamental problem for China’s real estate is that there’s too much supply and not enough demand.

In 2021, China built 1,565 million square meters (16.8 billion square feet) of property. Bloomberg Economics estimates that in the same year fundamental demand—for homes to live in, not as speculative investments—was 1,400 million square meters. By 2026 it’s projected to shrink to 1,100 million.

That means construction needs to fall 30% to bring supply in line with demand. So far it’s fallen 18%. China’s real estate correction—which has already tipped developers into default and taken a major shadow bank to the edge of collapse—is a little more than halfway done.

From here, there are multiple paths the property adjustment could take. An important reason for that: Construction has fallen, but sales have fallen more. Home sales in 2022 and so far in 2023 are 10% to 15% below our estimate of fundamental demand.

That suggests expectations of falling prices, uncertainty about the outlook for jobs and income, and hope for more enticements from the government are pushing buyers to delay purchases. In the least-bad scenario, moves to cut interest rates, reduce down-payment requirements and strip away other barriers to buyers will lift demand back in line with fundamentals. Supply still has further to fall, but with demand a little stronger that’s a less painful process.

In this scenario, real estate investment falls 8% in 2023 and an average of 5% per year from 2024 to 2026. Based on the past relationship, a 5% drop in real estate investment shaves about 0.6 percentage point from annual GDP growth.

China’s growth slows from about 5.4% this year to closer to 5% in 2024, and there are real questions about whether those numbers capture the conditions on the street. But recession and financial crisis are avoided. It’s a bumpy landing, but not a hard landing.

In a nightmare scenario, stimulus fails to revive confidence, sales continue to spiral down, and a larger and more painful correction in supply will be required—tipping more developers into default and raising the specter of a financial crisis.

To put some numbers on it, an overcorrection could see real estate investment down 20% or more at the end of 2023 and into 2024—taking the direct drag on annual GDP growth to 2.4 percentage points. And that wouldn’t be the end of the bad news.

On the current trajectory, we estimate developers’ short-term liabilities and funds required to finish pre-sold homes are on track to exceed their cash on hand, plus funds they will be able to raise through sales and fresh borrowing, by trillions of yuan in the months ahead.

That’s a gap too big for even Beijing to fill and means more pain ahead for homeowners (falling prices), developers (a hit to equity), banks (more bad loans), bondholders (haircuts) and the government (paying for a bailout). It’s not hard to see how the end result could be a financial crisis.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

In China’s state-owned banking system, a crisis would look more like Japan in the sclerotic 1990s than the US in the 2008 Lehman meltdown. Still, the damage would be severe, and it’s hard to say where the bottom for China’s GDP would be. Broadly in line with the findings of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff in their This Time Is Different history of financial crises, we assume 2024 growth would come in at zero—a drop of 5 percentage points.

When China sneezes …

For the US and other major economies, the gap between the Goldilocks and nightmare scenarios could be the difference between

a soft and hard landing. We use a suite of models to estimate spillovers through financial market, commodity price and trade channels—for the details, see the methodology below.

In the Goldilocks scenario, China’s GDP growth for 2024 comes in around 5%, 0.5 percentage point below our expectations earlier this year. For the US, that would mean a fractional drag—around 0.1 percentage point—on inflation and growth. The Fed would receive a little support in getting inflation back to its 2% target, but the impact would be marginal. The euro area and UK would see similarly limited effects.

In the nightmare scenario, where China’s 2024 growth goes from 5% to zero, spillovers are amplified. For the US, there’s a drag on CPI of 1.3 percentage points—overdelivering on the Fed’s target. GDP takes a 1.1 percentage-point hit—turning our baseline expectation of a shallow recession into a deeper downturn and pushing unemployment higher in an election year.

The impact on other major economies would be similarly severe, tipping the euro area from stagnation into recession and deepening the downturn we already anticipate in the UK. For China, even the dark cloud cast by the nightmare scenario has a silver lining. Growth driven by borrowing ever-increasing amounts to build ever more houses no one will ever live in wasn’t a sustainable development strategy.

At the end of the correction, China will have a smaller property sector and so more workers and capital devoted to productive uses. Surging sales of electric vehicles are one of the reasons to be optimistic about medium-term development prospects. Getting through the short term remains a significant challenge.

Methodology

We estimated global spillovers using three different models. Financial conditions were estimated following a structural approach based on the Bayesian Global VAR model (Bock, Feldkircher and Huber, 2020). We amend the model slightly by adding log real equity prices for each country as in Mohaddes and Raissi (2020).

Uncertainty in the financial markets is modeled as a global shock to equity markets in line with an increase in the VIX. For this estimation we reordered the countries starting from the US, euro area, UK and other economies such that the scaling is between the VIX and the US equity market. We use generalized impulse-response functions (GIRFs) as in Pesaran and Shin (1998).

The oil-price shock was simulated using the European Central Bank’s Global Model. We model the rise in oil prices as an oil-supply shock. In addition, since the US recently has become a net producer of oil, we include a US oil-production shock in the form of a US demand shock using the same model.

The China demand shocks were simulated using a four-country VAR model. The shocks were calibrated based on the assumptions that the drop in commodity prices is a result of China’s slump pushing oil prices down and that the fall in global equity prices is attributed to an increase in uncertainty from the China slowdown.

© 2023 Bloomberg