Almost every budget speech of the past decade has been called “pivotal”, “make or break” or something similar. And yet, the great pivot never seems to arrive. Except for the brief post-Covid commodity boom, a decisive change in the country’s fiscal dynamics has yet to materialise.

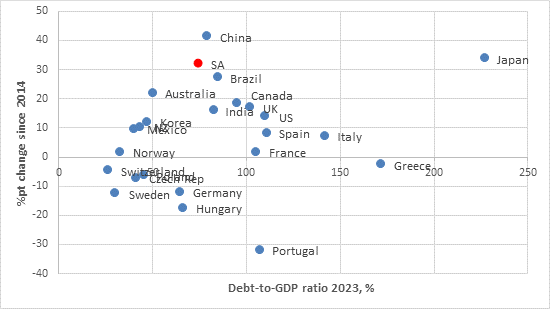

Instead, government debt levels have increased sharply. Year after year, the budget has projected a stabilisation of the debt-to-GDP ratio, yet it still rises. It is not high by international standards, as the chart below shows, but it stands out for how quickly it has increased in the last decade.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

Government debt-to-GDP ratios

Source: Bank for International Settlements

That is not because National Treasury lacks intent. Rather, it does not control all the levers of government finances, and external circumstances have not been helpful, particularly when Covid hit.

Importantly, National Treasury does not set wage increases for public servants.

It is another government department that leads the negotiations with public sector unions, and ultimately, it is a political, not technocratic, decision that determines the outcome. Successive rounds of wage agreements have been higher than what was pencilled in by Treasury, though there was some clawback when wages were frozen during the pandemic, breaking the steady upward trend.

Read: Budget 2024: How to save R30bn

The other problem has been the ongoing need to provide financial support to struggling state-owned enterprises that are not viable on their own anymore.

Eskom and Transnet bailouts were necessary due to their critical role in the South African economy (further support for Transnet could be announced this week).

Read: Fixing the twin icons of crisis bedevilling the country

However, support for other entities like SAA and the SA Post Office is arguably overtly political since these could easily be replaced by private companies.

The introduction of free tertiary education for low-income students in 2017 was also an unbudgeted political decision imposed on Treasury.

The big problem

But the biggest problem Treasury had to contend with is simply that the economy has underperformed expectations from 2014 onwards. Weaker-than-expected growth means lower-than-expected tax revenues – not helped by the hollowing out of the South African Revenue Service’s capacity during the Tom Moyane years (now thankfully largely reversed).

The current fiscal year (2023/24) has not been different. Although economic growth in 2023 has largely been as expected (the February 2023 budget speech forecast 0.8% growth), corporate tax revenues have disappointed. This is partly because of the big decline in commodity prices, particularly coal, from 2022 but also because 2023 was the worst year on record for load shedding. Companies had to spend billions on running generators and investing in solar and other alternative forms, denting their profitability.

Read:

Home, business solar installs doubled to 5GW last year

9 000 solar panels to power up MTN’s head office

Treasury’s energy bounce-back scheme off to a slow start

Meanwhile, spending has been running somewhat ahead of projections. This means the budget deficit – the difference between spending and tax revenue that must then be made up by borrowing – will be larger than anticipated in the 2023 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS). Expressed as a percentage of GDP, the deficit could be greater than 5%, compared to the 4.9% shown in the MTBPS.

This is politely termed ‘fiscal slippage’ by economists. While the finance minister will reiterate plans to reduce the deficit over the next three years, the larger new starting point means that it will take longer to stabilise the debt ratio, with a higher peak than the 77% forecast in November.

Of interest

All this borrowing (more than R350 billion per year in new debt and more than R100 billion in redemptions) takes place at very high interest rates. South African interest rates have always been relatively high because inflation has been rather high. However, in recent years, we have seen real borrowing costs rise as the bond market demands yields to compensate for the perceived higher risk of lending to the South African government.

And this creates a vicious cycle.

Read/listen: Government debt could reach 80% of GDP within the next two years

As the below chart shows, the government’s borrowing cost has exceeded the economy’s nominal growth rate over the past decade. This is not a complete coincidence since weaker growth has caused higher yields due to concerns over fiscal sustainability. This is a reversal from the usual international pattern where lower growth drags yields down as inflation expectations decline.

Today, however, the South African government borrows at 10% while national income only grows at 6%. Left unchecked, this is a recipe for trouble.

SA economic growth and government borrowing cost, %

Source: LSEG Datastream

What investors want to see

Therefore, the two most important things investors want to see in the budget are reforms that raise the economy’s potential growth rate and measures that will raise confidence in the longer-term fiscal outlook so that government bond yields can rerate – reducing effective borrowing costs.

The former can only really be done by letting go of state monopolies, crowding in private investment, and reducing the regulatory burden on businesses (sadly, there are still politicians who believe we can regulate and legislate our way to prosperity).

There isn’t money for a fiscal injection into the economy, but improved public service delivery can help.

As for lowering bond yields, it is completely out of the control of any official. The market will respond to evidence that things are going in the right direction.

There is little room for substantial tax increases to close the deficit since South Africa’s tax-to-GDP ratio is already quite high compared to peers. Instead, we will probably see modest tax initiatives, perhaps a bit more than the R15 billion pencilled in by the MTBPS.

Read:

Tax hikes pointless in weak economy, SA lender says

Possible area for additional tax revenue collections

Spending challenges

The heavy lifting will have to be on the spending side. Instead of slicing away at the allocations to all government departments, it is time for a wholesale review of departments, agencies and programmes so that spending levels can be brought in line with tax revenues and the government’s scarce financial resources can be redirected to where they are needed most and have the biggest impact.

President Cyril Ramaphosa promised such a thorough expenditure review, but it will likely have to wait until after the election.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

At the same time, looming in the background is perhaps the biggest increase in state spending in history if national health insurance (NHI) is introduced. Well-intentioned as it is, it cannot be accommodated in the current fiscal framework. It will be important to see if the budget makes any provision for NHI this year. The NHI Bill has been passed in parliament, despite objections that it is unworkable practically and financially, but has not been signed into law yet.

Listen: Why SA can’t afford the proposed NHI

Similarly, the current fiscal framework does not have room for a basic income grant. Over time, South Africa should expand the safety net that supports the poorest and most vulnerable members of society as funding becomes available. At the moment, the best we can do is extend and somewhat increase the R350 per month Social Relief of Distress grant, which the finance minister is likely to do.

No populist measures expected

Importantly, though, despite it being an election year, the budget will largely steer clear of populist measures. Despite all the criticism one might have of fiscal policy in South Africa, it is generally conducted within a sound framework. There are limits to foreign currency borrowing (the Achilles’ Heel of so many developing countries) and guidelines for the maturity profile of government debt (to avoid too many bonds coming due at once).

There is maximum transparency, with a three-year planning cycle announced every February and updated in October, including monthly spending and revenue data releases in between. Also, there is no history of election-driven fiscal cycles, unlike many other emerging markets. These guidelines could be formalised into fiscal anchors, legislated rules that could cap debt or deficit ratios, or similar. This is something Treasury has been discussing for some time as a means of enhancing fiscal policy credibility (only if adhered to, of course).

Read: SA weighs new fiscal anchor to help contain debt surge

This also extends to the GFECRA, the gold and foreign exchange contingency reserve account. GFECRA is effectively the unrealised gains on South Africa’s foreign exchange reserves, held by the Reserve Bank but accruing to the government.

The depreciation of the rand means this now stands at R450 billion.

Unlike in the rest of the world, there hasn’t been a regular transfer of these gains from the central bank to the government.

Treasury has been discussing the matter with the Reserve Bank, and the finance minister will likely reference these ongoing discussions without making any firm announcements.

Read: Should SA tap R497bn in paper profits?

In a nutshell, it would be beneficial to realise some of the gains – perhaps around R100 billion – but there are complexities. It would involve selling down forex reserves, and by the IMF’s estimates, South Africa’s forex reserves are already on the low side. If and when GFECRA gains are transferred to Treasury, communication will have to be key, reiterating that the Reserve Bank’s operational independence remains intact, that all transfers will be done in a transparent, rules-based manner and that the proceeds will be used for a specific goal, such as paying off debt. It can help lower the debt burden but is not a silver bullet.

Investment implications

Most South Africans probably only follow the budget to see what happens to tax rates, with the ‘sin’ taxes on alcohol and tobacco usually getting disproportionate attention.

However, they should probably care more about what it means for their retirement investments. The budget is of most direct relevance to the bond market as it determines the government’s borrowing requirement and the size of bond supply, and it is a statement about long-term fiscal sustainability and default risk.

Substantial bond issuance can lower bond prices and raise yields but should be priced in already, judging by the numerous detailed pre-budget analyses out there.

Default risk is a longer-term uncertainty markets grapple with. Eventually, the rising interest burden might get to the point where the government of the day decides to prioritise paying salaries, say, over making interest or capital payments. A default would be extremely short-sighted since the government would cause tremendous damage to the financial system, with banks, pension funds and insurance companies being large holders of government debt, even more so in recent years as foreign investors have stepped back. But also, since it would still need to borrow money after a default, it cannot afford to alienate lenders.

To be clear, the risk of a default in the near future is extremely low.

Recent government defaults occurred when interest payments consumed 40% to 50% of tax revenues, whereas it is currently 21% in South Africa (up from 12% a decade ago). These defaults have also overwhelmingly been on foreign currency debt. Servicing foreign currency debt is difficult since the money needs to be earned internationally. It is also difficult because liquidity can dry up in these offshore bond markets. With around 90% of South African government debt denominated in rands, the Reserve Bank can provide liquidity to the local bond market to reduce the risk of an accidental default.

The credibility of the Reserve Bank as an independent long-term inflation fighter is a key anchor of domestic bond valuations. Investors do not have to worry too much about long-term inflation risks. After all, surprisingly high inflation is a stealth default on the real value of debt commitments.

FTSE/ JSE Financial & Industrial Index return decomposition, Jan 2015 to Feb 2024

Source: LSEG Datastream

The budget matters for equities, too, but indirectly. Elevated borrowing costs have contributed to the depressed valuation of South African equities, though, of course, it is not the only factor, with commodity prices and China also playing a role.

The above chart shows a simple return decomposition of the FTSE/JSE Financial & Industrial Index (Findi) since January 2015. The Findi is admittedly an imperfect proxy for SA Inc since it contains several large global companies. However, it is still useful to consider.

Earnings growth was 140% over this period (10% annualised), but the valuation (the price-earnings ratio) declined by 35%. This broadly corresponds to the 38% increase in borrowing costs (as the 10-year government bond yield rose from 7% to 9.8%). A decline in bond yields should eventually support a higher valuation for local shares, but again, it won’t be the only factor at play.

Read: The valuation debate: Friend or foe when investing?

In summary, though this week sees another pivotal budget speech, there will be no pivot. It will be a long, hard slog to get government finances on a sustainable footing, but the finance minister will reiterate his commitment to doing so and emphasise ongoing growth-enhancing structural reforms.

Cheap local bonds and equities (and the currency) are only likely to rerate once these reforms gain traction.

For the time being, however, bond investors can still ‘clip the coupon’ and should focus on the very juicy real interest rates they are earning rather than the ongoing price volatility.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth.