Stephen James Hubbard left America behind decades ago, first for Japan, then Cyprus and finally Ukraine. He didn’t like the government — any government, really.

He was a wanderer, growing up in a small town in Michigan and traveling the world before ending up alone in the eastern Ukrainian town of Izium when the Russians invaded on Feb. 24, 2022.

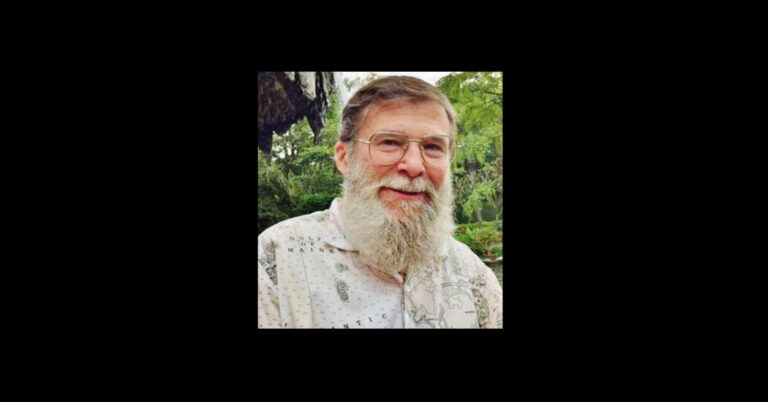

Now Mr. Hubbard, a retired English teacher who turns 73 on Thursday, has become an unlikely pawn in an international war. The Russians arrested him shortly after invading and accused him of fighting for Ukraine. They moved him to at least five different Russian detention centers before putting him on trial on a charge of being a mercenary.

In October, a Moscow court convicted him and sentenced him to almost seven years in a penal colony.

His case has remained mostly under the radar. But last month the State Department said Mr. Hubbard was “wrongfully detained” — elevating his case and indicating that the United States believes that the charges are fabricated.

A State Department spokesman said he never should have been taken captive or moved to a Russian prison.

Mr. Hubbard’s sister and three former Ukrainian prisoners of war held with Mr. Hubbard dispute that he fought for Ukraine. The former prisoners say they believe he will die if he is not freed. They say he endured the same torture they did: repeatedly beaten, terrorized by dogs, forced to stand all day, every day, even stripped naked for more than a month.

“They’d beat our ankles and force us into the splits, tearing ligaments in the process,” said Ihor Shyshko, 41, who said he shared a cell with Mr. Hubbard. “Many of the men were injured, some permanently. The conditions were beyond inhumane.

“The same thing happened to Stephen, but it was even worse for him because he’s an American,” added Mr. Shyshko, who was freed in a prisoner exchange last summer. “They stormed in, shouting in the hallway: ‘We know you’re an American. You’re dead here!’”

The United States has accused Russia of inflating and inventing criminal charges against Americans so they can be traded for Russians held elsewhere or used as international bargaining chips. After a major prisoner exchange in August, Mr. Hubbard is one of 13 Americans now known to be held in Russian prisons. Mr. Hubbard is the oldest. He is also the only American known to be imprisoned in Russia after being taken from Ukraine.

Only one other American now being held has been publicly designated as wrongfully detained in Russia.

Mr. Hubbard’s family has not been able to find his prison. The Russian judge removed his case file, including even basic information like his lawyer’s name, from public view. The New York Times also could not locate him.

The U.S. Embassy in Moscow has not seen Mr. Hubbard, despite Russia’s obligation to grant access, a State Department spokesman said. The embassy said it would not comment on his case because of privacy concerns.

Mr. Shyshko said he tried to ask the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv for help, but he could not get past the front door.

Patricia Hubbard Fox, 71, Mr. Hubbard’s only sibling, said, “It’s just really very upsetting,” adding, “And now they’ve taken everything from him, even his glasses.”

A Quiet Life

Mr. Hubbard had always been a solitary man. He liked his privacy. He didn’t like email and social media. He was suspicious of government agencies that might be spying on internet posts and of what the government spent taxes on.

He and his sister grew up in Big Rapids, a very small Michigan city. Their single mother sometimes abused them. “We grew up at the end of a bullwhip,” Ms. Hubbard Fox recalled.

As an adult, Mr. Hubbard always seemed to be searching: He enrolled in a Bible college in Tulsa, Okla., but lasted only a year. He married young, at 20.

Mr. Hubbard enlisted in the Air Force, but he left after three years of active duty and two in the National Guard, mainly in Sacramento, records show. He worked as an educational assistant with the local veterans affairs department and studied at a nearby business college. His marriage fell apart and Mr. Hubbard’s wife won custody of their three children.

Mr. Hubbard landed in Seattle, where he earned a master’s degree in English and met the Japanese woman who became his second wife, Ms. Hubbard Fox said.

In the mid-1980s, the couple moved to Japan, where Mr. Hubbard taught English and joined the Eastern Orthodox Church. The couple had a son before divorcing. After his son grew up, Mr. Hubbard moved to Cyprus, where a son from his first marriage lived and where he fell in love with another woman, Inna. She was Ukrainian.

In 2014, they moved to Izium. When he needed money, he told his sister, he taught English online. He spoke no Ukrainian, no Russian.

Ms. Hubbard Fox said she last spoke to her brother on Skype in September 2021, as he sat down to eat some porridge.

It’s not clear whether the couple had separated or whether Inna was on vacation. But when the Russians invaded in February 2022, Mr. Hubbard was alone.

Weeks later, the Russians captured Izium. The following day, April 2, 2022, Mr. Hubbard was detained, the RIA Novosti state news agency later reported.

The circumstances are murky. The Russian authorities said Mr. Hubbard had signed up that February — the month he turned 70 — for the regional territorial defense unit to defend Ukraine and received training, weapons, ammunition and $1,000 a month. They said he was arrested while manning military checkpoints.

That was unlikely, said Alyona Hryban, a civil servant in Izium. She said the territorial defense unit had few weapons. No one was paid. “There were no old men there,” she added.

Mr. Shyshko recalled that Mr. Hubbard said he was detained at a checkpoint while fleeing.

“He wanted to get out of there, but he couldn’t,” Mr. Shyshko said.

‘He’s Every American’

Mr. Hubbard’s first detention camp was five miles over the Russian border. Andrii Stratulat, another prisoner of war, said the Russians gave Mr. Hubbard two English books: “The Egg and I,” a 1945 memoir by a young wife on a chicken farm, and “The Lovely Bones,” a 2002 novel about a young girl whose spirit comes to terms with her rape and murder. He read them over and over.

Mr. Stratulat, who spoke English, was put in Mr. Hubbard’s tent in June 2022.

“He said that day he started to smile,” recalled Mr. Stratulat, 30.

They spent 42 days together, Mr. Stratulat said. Mr. Hubbard talked about his life: A trip he took to the Grand Canyon. His baptism into the Eastern Orthodox Church. His Japanese wife, Sumi. Their son, Hisashi. His partner, Inna.

Throughout his imprisonment, Mr. Stratulat would recite those names to himself: Hisashi. Sumi. Inna. When he was freed, he wanted to tell someone about the American he had met.

In late July 2022, Mr. Hubbard was transferred, Mr. Stratulat recalled.

A captured Ukrainian special forces officer with the call sign of Hacker met Mr. Hubbard in the Stary Oskol prison in Belgorod, about 80 miles northeast of the detention camp, in early September. After an interrogation that was more like torture, Hacker said, he was taken to a cell with Mr. Hubbard, who gave him water and prayed for him.

“It’s the first time some guy, an old guy, a wise guy, prayed for me,” said Hacker, 33, whom The Times is identifying by his military call sign because he is still fighting Russia.

Hacker said he met Mr. Hubbard again about a month later, in Novozybkov prison. For two months, they were housed in nearby cells. “I heard everything that was happening to him,” recalled Hacker, who was freed last spring.

Mr. Hubbard had problems with his kidneys, stomach and rectal tract, Hacker said. He was bleeding. The Russian guards beat him and forced him to learn Russian words, Russian poets, the Russian national anthem.

“The soldiers, guards and special forces looked at him as an archenemy,” Hacker said. “Because Stephen, he’s the American. He’s the American spider. He’s the American from Michigan. He’s every American.”

Because Russian officials have disclosed no information about Mr. Hubbard, the former prisoners’ accounts are impossible to verify. But they aligned with one another and with those of other Ukrainian prisoners of war.

In 2023, Mr. Hubbard was moved to a prison in Pakino, about 170 miles east of Moscow, where he shared a cell with Mr. Shyshko and 13 other men, Mr. Shyshko said.

There, prisoners were interrogated, often tortured, shocked with electricity, beaten and burned, Hacker and Mr. Shyshko said.

After the Russians found scabies on prisoners, they were all stripped and taken to a cold basement, where they were forced to walk naked in circles wearing only slippers for a month and a half, Mr. Shyshko said.

Mr. Shyshko said the doctor told him “‘the scabies mite can’t reproduce in the cold, it’ll die along with you.’”

Lunch was often boiled water with a few cabbage leaves; dinner, leftovers from Russian inmates, blended together. Mr. Shyshko’s weight dropped to less than 130 pounds from about 240.

“Stephen, though, he never gave in,” Mr. Shyshko said. “He kept telling us: ‘These people aren’t human. Don’t lose hope.’ He stood up to them and encouraged us to hold on.”

One day, Mr. Hubbard said he thought his sister might be looking for him.

A Prison Sentence

Ms. Hubbard Fox worried about her brother when the war started. But she couldn’t reach him. Eventually she found out the Russians had him: She saw an interview on Russian TV in which he echoed Russian talking points — prisoners of war often are told what to say — and another video, posted briefly on X, where guards hit Mr. Hubbard with a sandal.

She said she tried to talk to the American authorities, but got little help. And she wasn’t sure whom to call.

In mid-May 2024, Mr. Hubbard disappeared from the prison in Pakino and later surfaced in court proceedings in Moscow. At one hearing, before the judge closed the trial to the public, RIA Novosti reported that Mr. Hubbard had pleaded guilty to being a mercenary, saying from the dock, “Yes, I agree with the indictment.”

Early last October, Mr. Hubbard — bent over, his hair and beard roughly chopped, his glasses gone — was sentenced to six years and 10 months in a prison colony.

Ms. Hubbard Fox said she hoped President Trump could deal with the Russians. “He’s a doer, and they know that he’s not going to put up with their crap,” Ms. Hubbard Fox said.

She said that seeing her brother beaten with a sandal reminded her of seeing him abused as a child. She plans to sell her home in Colorado and buy one in Oklahoma, so her brother can live with her when he gets out.

“I love my home, but my brother’s lost everything,” she said. “So I’m doing this. I’m going to provide him a home.”

Reporting was contributed by Hisako Ueno from Tokyo; Dzvinka Pinchuk, Yurii Shyvala and Oleksandra Mykolyshyn from Kyiv; and Shawn Hubler from Sacramento. Susan Beachy contributed research.