In the world’s second-biggest ESG debt market, corporate clients are starting to walk away.

Extra regulatory requirements, fewer financial incentives and the risk of being accused of greenwashing are putting off clients who just a few years ago were champing at the bit to attach an environmental, social or governance label to their financing, according to bankers and lawyers close to the market.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

The products in question are so-called sustainability-linked loans, a market that BloombergNEF has estimated is worth $1.5 trillion, making it second in size only to the global market for green bonds. Largely unfettered by regulations, borrowers and financiers have been relatively free to construct their own standards for SLLs. But as financial watchdogs start to erect guardrails around ESG labeling, a broader market retreat appears to be underway.

Last year, issuance of SLLs plummeted 56% to $203 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Though 2023 was a tough year across debt markets, the decline for SLLs was almost twice as precipitous as it was for green loans. What’s more, green loan sales have roared back to life in 2024, while SLL issuance has continued to decline, having plunged 74% so far this year, the Bloomberg data show.

Rachel Richardson, head of ESG at London-based law firm Macfarlanes, says this year might be “a bit of a crunch point for both borrowers and lenders” in the market for sustainability-linked loans.

“When it comes to refinancing SLLs from three or four years ago, both borrowers and lenders are going to have to have a really hard think about where the market was then — in its total infancy — and where the market is now,” Richardson said. The question then becomes “whether it’s still appropriate for them to continue borrowing via an SLL.”

A key factor behind the slide in SLL issuance is the enforcement of a European Union regulation requiring companies to document their ESG claims, according to one of the bankers Bloomberg interviewed, who asked not to be named discussing private deliberations. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive is now forcing companies that do business in the bloc to provide vast amounts of data to back up virtually every sustainability statement they make.

Though CSRD wasn’t written to regulate SLLs, corporate clients are increasingly pointing to the directive as a disincentive to tap the SLL market, given the heightened risk of being accused of greenwashing, the banker said.

It’s the latest sign of trouble in the least transparent corner of ESG deal-making. Last year, the Financial Conduct Authority issued a stern warning targeting the SLL market, which it said risked being the subject of “accusations of greenwashing.”

Click here to see which banks are most active in the SLL market today.

What BloombergNEF Says:

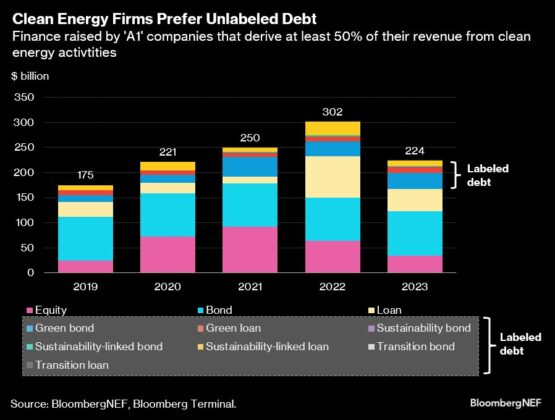

There’s now clear evidence that even “clean energy companies prefer to get funding through regular debt rather than instruments explicitly labeled as green,” BNEF’s Maia Godemer said in a report on Monday. BNEF “looked at more than 5,300 firms that generate at least 50% of their revenue from clean energy activities, calculating they raised more than $224 billion of financing last year, of which $190 billion came from debt,” she said.

Another disincentive for issuers is the virtual disappearance of the SLL greenium — the premium, or lower coupon, that ESG borrowers once enjoyed — according to bankers Bloomberg interviewed. The 10 basis points an SLL borrower was once able to save has now been largely eroded by the cost of annual audits associated with SLLs, one banker explained.

“Some people will feel an SLL is no longer appropriate” in part because “they don’t want to stomach the extra costs of the second-party opinions and assurance,” Richardson said.

To be sure, there are still green issuers using the SLL market. Last week, Siemens Energy AG obtained a €4 billion credit line tied to the company’s sustainability performance. And other European renewable energy firms continue to avail themselves of SLLs as they refinance debt that’s coming due, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

More broadly, however, many clients who a few years ago had attached sustainability labels to revolving credit facilities now appear to be rolling over those RCFs as regular loans, according to one of the bankers Bloomberg interviewed.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

Another SLL banker spoke of a growing trend among clients not to honor so-called rendezvous clauses. Under these, borrowers who agreed that regular loans would become SLLs once sustainability targets are more achievable aren’t actually following through on those agreements, the banker said. The size of this silent corner of the SLL market is unknown, but substantial, the banker said.

What Is a Sustainability-Linked Loan:

An SLL is a loan — mostly in the form of a revolving credit facility — that requires the borrower to live up to sustainability requirements expressed as so-called key performance indicators. SLLs are similar to sustainability-linked bonds in their structure, but come with far less public documentation as they tend to be bilateral agreements between borrowers and their bankers.

Borrowers often publicly tout their ability to do SLLs as proof that their sustainability claims are legitimate. Banks have tended to include such products in their overall sustainable financing targets, though a growing number of lenders has ceased to do so, due to the perceived risk of being accused of greenwashing, Bloomberg has previously reported.

The products remain unregulated, but the Loan Markets Association last year published updated voluntary guidelines urging borrowers and bankers doing SLLs to only use KPIs that are “relevant, core and material” and to ensure that KPIs are also “measurable and quantifiable.” It also advocated the use of external verification. The guidance only applies to SLL deals struck after March 9, 2023.

The sustainability-linked loan market came into being about seven years ago as ESG was morphing into a must-have label spurring its own boom in capital markets. And with virtually no specific ESG regulations, adding the label to products was a low-risk undertaking.

Between 2018 and 2021, the SLL market soared more than 960% to $516 billion of annual deals, according to data provided by BloombergNEF. Green bonds, which must abide by so-called use-of-proceeds clauses, grew a more modest 250% in the same period to just over $640 billion worth of annual deals.

The 2021 arrival of more comprehensive ESG investing regulations laid the foundations for some of the exuberance around SLLs to subside. When the end of the pandemic then set off a cycle of inflation, higher interest rates and a spike in energy demand exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, sustainability-linked products woke up to a completely new reality.

According to Richardson at Macfarlanes, some of the SLL deals that went through four years ago are actually “pretty weak from an ESG perspective.” So the SLL market is now “taking stock of what is acceptable,” she said.

© 2024 Bloomberg