Not everybody can be famous, but everybody can be great, because greatness is determined by service. Martin Luther King

The Monarch Butterfly is known for its incredible long-distance migration, one of the most remarkable natural phenomena in the insect world. The monarch butterfly migration is a fascinating feat of endurance and navigation, spanning thousands of miles. During their journey, multiple generations add another layer of uniqueness to their story. The couple mated after wintering will not return; their offspring will somehow.

Female monarchs lay their eggs on milkweed plants, the sole food source for monarch caterpillars. The eggs hatch into caterpillars, which feed on milkweed leaves for about two weeks, molting several times as they grow. The caterpillar forms a chrysalis, a green casing where metamorphosis occurs. After about 10-14 days, the adult butterfly emerges from the chrysalis.

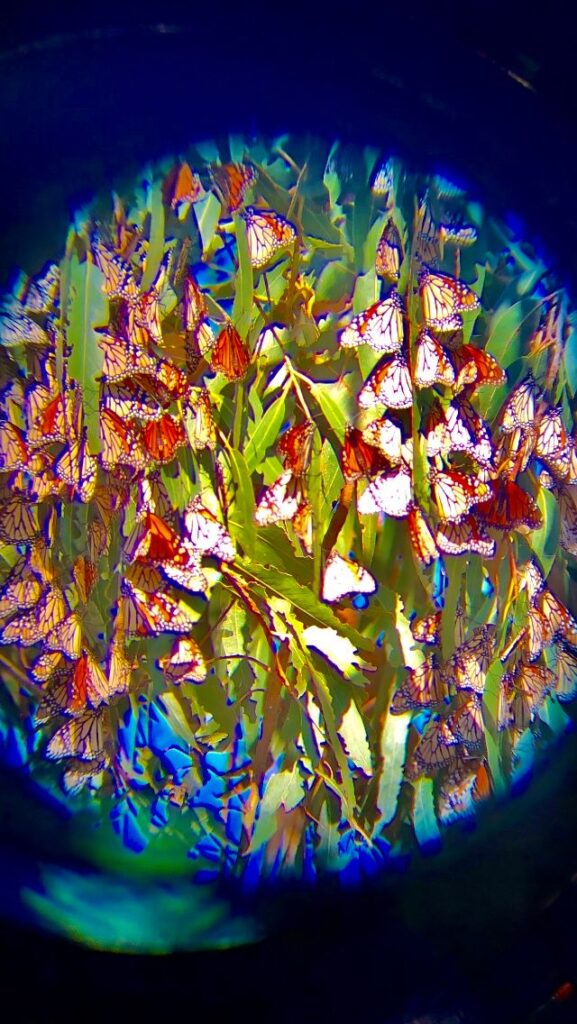

Monarchs east of the Rocky Mountains migrate from the United States and southern Canada to overwintering sites in the Mexican state of Michoacán. Those west of the Rockies migrate to sites along the central California coast where the above photo was taken. Monarchs form dense clusters on trees at the overwintering sites to conserve heat over the winter months.

As the winter ends and temperatures warm in late February/early March, the butterflies become reproductive. After their long migration and mating efforts, the mated males have depleted fat reserves and die shortly after the mating. The newly mated females live on to begin the northern migration laying eggs and producing the next generation.

The Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve was established in 2006 and inscribed on the World Heritage List two years later. Every autumn several million butterflies from eastern North America cluster there. In the spring, they begin an 8-month migration to eastern Canada and the US before returning although it was never home.

The Mexican state of Michoacán is located in western Mexico along the Pacific coast and covers an area of around 23,000 square miles. It contains parts of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt mountain ranges and has a varying climate from tropical along the coast to temperate in the highlands.

Agriculture is a major part of the economy. The state is a leading producer of avocados, supplying over 80% of Mexico’s crop. Other major crops include corn, sugar cane, strawberries, and mangoes. Tourism focused on colonial cities, beaches, and the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve

The area has struggled with drug cartel presence and violence, especially in recent decades. Illegal logging and avocado production are tied to cartel activities.

The Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) emerged around 2010 as an offshoot of the Sinaloa Cartel, quickly becoming one of Mexico’s most powerful and violent criminal organizations. It is based in Jalisco but has spread its operations across multiple states including Michoacán, Guerrero, and Veracruz.

The cartel is heavily involved in drug trafficking but has diversified into other illicit activities like extortion, kidnapping, fuel theft, and illegal mining/logging. It is known for its bold tactics, openly confronting military and police forces. The cartel uses extreme violence to assert its dominance, often leaving piles of dismembered bodies as warnings. The U.S. has designated the CJNG as one of the most dangerous transnational criminal groups.

Avocados and Logging. Consumption of avocados has tripled in the U.S. from 2001-2020, with 90% coming from the Mexican state of Michoacán. This intensive avocado production is causing significant environmental damage. Avocado monocultures lead to deforestation, soil erosion, increased pesticide use, and strain water resources as avocado trees consume much more water than native plants.

The popular Hass avocado variety was originally bred in California but introduced to Michoacán in the 1950s. Mexican farmers converted to growing mainly Hass avocados to export to the lucrative U.S. market after NAFTA. Avocado production has cleared forests, eroded fertile soil, and drained aquifers in Michoacán, harming indigenous communities. Violence and corruption have also increased around the lucrative industry.

Mexican officials estimate avocado production led to the clearance of 2,900 to 24,700 acres of forests per year from 2010-2020 in Michoacán. This rapid expansion of avocado orchards in Michoacán has contributed to the region’s unsanctioned and environmentally damaging deforestation facilitated by illegal logging practices.

Homero Gómez González was born (c.1970) in El Rosario in eastern Michoacán. His family was in the logging business. He grew up cutting down the town’s timber and selling it as did many others since it was the basis of the local economy. He studied at Chapingo Autonomous University, a popular agricultural college, and became an agricultural engineer. He returned home to the logging industry.

By the early 2000s, Gómez had become aware of the impacts of deforestation and stopped logging. He was skeptical of conservation efforts because of the loss of jobs and poverty. Gómez became knowledgeable about tourism and developed the idea of a sanctuary. He collaborated with conservationists at the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. The El Rosario Monarch Butterfly Preserve was established as a component of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve which he managed and served as spokesperson.

His influence was broadened when he became the municipal president and commissioner of El Rosario. Gómez worked with governmental agencies to increase stipends for local farmers to preserve trees. He managed 150 hectares of reforested land and encouraged communal landowners to reforest corn fields.

Protecting the monarch butterflies’ migratory home became his mission. He documented his work, the challenges, and images of monarch butterflies on social media. As the preserve manager, Gómez was on the front lines defending the reserve’s lands from encroachment by drug traffickers and criminal groups involved in unauthorized deforestation.

At first, logging was limited and then outlawed but 461 hectares were lost to illegal logging in Michoacán between 2005 and 2006. Entire swaths of the forest were destroyed including the primary habitat for the butterflies. He attempted to keep loggers out of the reserve, and organized marches, demonstrations, and anti-logging patrols.

Gómez, age 50, disappeared on Jan 13, 2020, one of more than 61,000 people missing in Mexico – the majority are suspected to be victims of criminal organizations. His body was found in an agricultural reservoir in Ocampo more than two weeks after his disappearance. A few days later the body of Raúl Hernández Romero, another activist and guide connected to the butterfly sanctuary who disappeared at the same time, was identified.

Their deaths highlight the grave risks faced by environmental defenders in Mexico, especially those combating powerful criminal organizations profiting from exploiting and degrading natural resources like old-growth forests.

In my book The Tall Poppy Syndrome: The Joy of Cutting Others Down I devoted a chapter to TPs titled “Tall Poppy Hall of Fame.” To be included one had to serve. The TPs possessed courage, fortitude, justice, wisdom, and selflessness. Dian Fossey was included. She and Gómez shared another fate – death.

Gómez made protecting the monarch butterflies’ migratory home his mission until he ultimately sacrificed his life for this cause.