It’s either the rule of law or the law of the ruler.

Fuad Alakbarov

As a researcher-teacher, I routinely attempted to reduce one of my peer-reviewed publications into one slide. Researching, and doing the “dirty work” especially if a prospective study and publication cause many to yearn to showcase how much one knows on the subject. This process prevents showmanship and showcases the essence of the study.

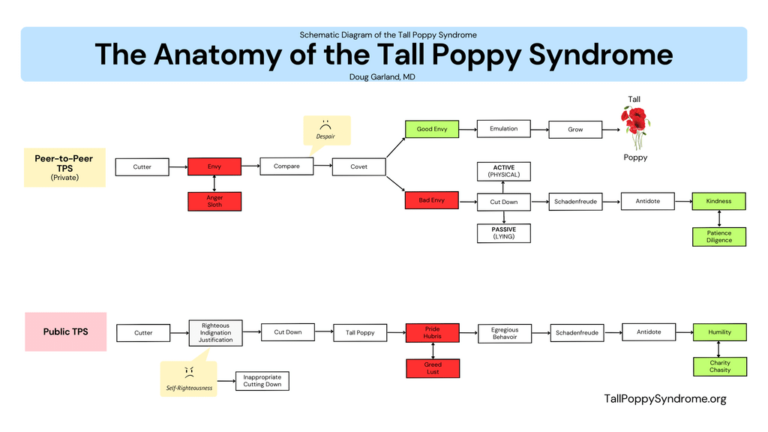

It also allows both a short or in-depth presentation with one slide. Placement of many publications can be placed in one canned talk. The above diagram displays many hours of research, thinking, and writing and originated from my book The Tall Poppy Syndrome – The Joy of Cutting Others Down. A previous blog explains the slide: Anatomy of the Tall Poppy Syndrome.

While studying TPS I relied heavily on the Australian Dr. Norman Feather’s work: Tall Poppies, deservingness and schadenfreude. He believed the cutter often harbored envy and the TPs were justifiably cut down due to their egregious acts. The slide shows my expansion on those concepts.

This blog will demonstrate how one can expand Feather’s and my work by widening the TPS lens. Although acknowledged in my book, fear has not been a constant part of my writing but is an integral aspect of TPS. Fear can be used to control and cut poppies or the poppies can harbor fear that prevents them from growing tall.

Culture of Fear. The term gained prominence in the latter half of the 20th century, particularly in the fields of sociology, psychology, and political science. Its conceptualization emerged as scholars analyzed various social phenomena characterized by pervasive fear and anxiety.

Frank Furedi’s work, particularly his book “Culture of Fear: Risk-Taking and the Morality of Low Expectation” published in 1997, delved into how modern societies increasingly embrace fear as a means of governance, risk management, and social control. This entity encompasses systemic and institutionalized mechanisms through which fear is generated, sustained, and normalized within a given context.

Cold War Era: The geopolitical tensions of the Cold War fueled a culture of fear in both Eastern and Western blocs. The threat of nuclear annihilation, government surveillance (more below), and propaganda campaigns heightened anxieties and shaped public discourse and policy decisions.

Post-9/11 Era: The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, significantly impacted global perceptions of security and risk. Governments around the world implemented extensive security measures, surveillance programs, and counterterrorism policies, often fostering a climate of fear and suspicion.

Totalitarian Regimes: Throughout history, totalitarian regimes like Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, and Maoist China have systematically used fear to maintain power and control over populations. Mass surveillance, censorship, political purges, and state-sponsored violence were common features of these oppressive systems.

Media and Public Discourse: Mass media, particularly sensationalist news coverage, has been criticized for perpetuating a culture of fear by emphasizing crime, violence, and sensationalized threats. This focus on negative and fear-inducing stories can distort perceptions of risk and contribute to heightened anxieties within society.

Corporate Environments: In some corporate cultures, fear is used as a management strategy to increase productivity and compliance. Threats of job insecurity, punitive measures for underperformance, and a lack of psychological safety can create a culture where employees feel constant pressure and anxiety.

Climate of Fear. This term refers to the immediate or prevailing atmosphere or mood within a specific setting or situation. It may arise as a result of particular events, circumstances, or actions that induce fear and uncertainty among individuals or groups. A climate of fear can be temporary and fluctuate depending on external factors or internal dynamics.

I devoted writings in my book regarding “scares” especially our government’s: immigrants (exclusion acts), Red, and Lavender Scares. All culminated in the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and Joseph McCarthy who claimed he had a list of members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring who were employed in the State Department.

Below is a case study from my book on Tall Poppy Dalton Trumbo who a fearful US government cut down:

Dalton Trumbo and the Hollywood Ten

On December 9, 1905, James Dalton Trumbo was born in Montrose, Colorado, and relocated with his family three years later to Grand Junction. While in high school, he was a cub reporter for the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel. He graduated in 1924 and spent a year at the University of Colorado, where he wrote for various school organizations and the Boulder Daily Camera.

Trumbo’s family moved to California after his father lost his job. When his father died in 1926, Trumbo worked various odd jobs to support his mother and two sisters. Ten years of steady night work at a bakery allowed him to attend the University of Southern California, although he never obtained a degree. He also produced movie reviews and short stories.

Trumbo wrote earnestly in the 1930s; he published articles in mainstream magazines, wrote for the Hollywood Spectator, and published his first novel, Eclipse. As a reader in the story department at Warner Brothers, he evaluated plays and novels as possible motion pictures, then signed a contract as a junior screenwriter for B pictures and received his first screen credit for Road Gang. He met his future wife at Warner and married her two years later. In 1937 he signed with MGM, which afforded better assignments.

A shadow was creeping toward Hollywood, however. From 1938 until 1975, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigated supposedly subversive, disloyal activities by private citizens, public servants, and organizations suspected of a Communist affiliation. HUAC had the power to subpoena witnesses and hold people in contempt of court. They often pressured witnesses to provide names and other information about Communists and sympathizers. The tactics of HUAC were a form of “red-baiting,” a logical fallacy that discredits others’ arguments by accusing, attacking, or persecuting the opponents as Communists, Socialists, Marxists, anarchists, or those sympathetic toward their causes.

In 1938 Chairman Martin Dies Jr. released a report that Communism was pervasive in Hollywood. A former Communist Party member named forty-two movie professionals, many of them popular movie stars, to a Los Angeles grand jury, and someone leaked their names to the press. Those on the blacklist could clear their names if they met with Dies, which they did, of course. The grand jury cleared all of them except Lionel Stander, whom Republic Pictures promptly fired in spite of his contract with them.

By the 1940s, Trumbo was writing A-list pictures and received his first Oscar nomination for Kitty Foyle. He was well respected and highly paid, but he established himself as a left-wing political activist and American Communist Party (CPUSA) sympathizer. Trumbo was part of the anti-Fascist Popular Front, a coalition of Communists and liberals. The group dissolved when many quit in disgust over the nonaggression pact the USSR signed with Nazi Germany.

Trumbo’s antiwar novel Johnny Got His Gun had won the American Booksellers Book of the Year Award as the most original book of 1939. Pro-peace and anti-FDR, CPUSA felt the novel was the genre of literature needed to prevent the US from entering WWII. When Germany invaded Russia in 1941, however, CPUSA reversed its stance and Trumbo ordered his publisher to cease publication and recall all copies of his book.

Within a few months, the US entered the war. The book became popular among peace lovers and isolationists but was difficult to find. During the early war years, Trumbo received letters denouncing Jews and using Johnny Got His Gun to support negotiating peace with Germany. He turned over the letters to the FBI.

In 1943 he embraced the Communist Party’s peace platform and formally joined its ranks. He soon realized his political views would affect his career. Although he had written the screenplay for the popular patriotic war movie A Guy Named Joe, its 1943 Oscar nomination went to the authors of the story on which it was based.

Trumbo and his compatriots wrote prowar material much more often than Communist information. His movie Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo was based on the Doolittle Raid; however, Tender Comrade loosely depicted socialism and the collectivization of three women working in the defense industry while their husbands fought on foreign soil.

American Business Consultants Inc. had insider information from the FBI and HUAC. On June 22, 1950, their Red Channels pamphlet listed 151 entertainment-industry employees as Communists or sympathizers. Over time these and more were named and banned from entertainment employment.

Trumbo’s last screenplay before being blacklisted was Our Vines Have Tender Grapes (1945), which had a collectivistic bent. The movie starred Edward G. Robinson, who was on the gray list of Fellow Travelers, who had implied Communist sympathies but not enough evidence for validation. Meanwhile, CPUSA more aggressively attempted to influence Hollywood party members to reflect the party’s ideological agenda. The film did not do well at the box office.

While looking for Communists and Fellow Travelers in 1946, HUAC denounced Trumbo’s Tender comrade as a Communist propagandist. But a friendly witness testified that left-wing screenwriters did not imbue such ideologies into movies. He offered A Guy Named Joe and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo as examples.

Renowned cutter William R. Wilkerson’s Hollywood Reporter named Trumbo and other purported Communists and sympathizers. More columns followed that added names to “Billy’s List,” or “Billy’s Blacklist.” (Sixty-five years later, Wilkerson’s son would apologize and state his father had been motivated by revenge for his foiled ambition to own a studio.)

Based on this list, HUAC opened hearings in 1947 on whether the people named were sowing propaganda in movies. The committee called forty-three of them as witnesses, but nineteen would not give evidence. Congress called eleven of the nineteen to testify, but only Bertolt Brecht sang. The other ten stood on their First Amendment rights to free speech and assembly. Without evidence of wrongdoing, the committee cited them with contempt of Congress and began criminal proceedings.

The Hollywood Ten refused to testify, and in 1948 each received a one-thousand-dollar fine and one-year prison sentence. Appeals followed all the way to the Supreme Court, which refused to hear their case. The Hollywood studios blacklisted them, and the Screen Writers Guild—founded by three members of the Hollywood Ten—kicked them out. Trumbo knighted himself the “martyr of freedom of speech,” but others claimed he and his group were doctrinaire Communists and hypocrites who would not fight for free speech for all people. In 1950 they began their one-year prison terms. Trumbo served eleven months at a federal penitentiary, then sold his ranch and moved to Mexico City with his family.

Although he still wrote scripts, he used pseudonyms for thirty of them. Others on the blacklist used “fronts,” as well, who took credit for their works and paid the writers from the proceeds.

Trumbo’s script for Roman Holiday (1953) had ten Oscar nominations and won three, including one for screenwriting, which he could not claim. Chronicling the difficulties of Mitchell mentioned earlier in this chapter, The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell (1955) won for director. And The Brave One (1956), penned for the King Brothers, won a screenwriting Oscar. The story credit went to Robert Rich, the film producer’s nephew. When the winner did not show up at the 1957 Academy Awards, the producer denied the claim.

Rumors circulated that Trumbo was the unknown writer of The Brave One, and debate broke out concerning the propriety of the blacklist. The studios were the main winners since the blacklist lowered writers’ fees.

In 1958–1959 Trumbo wrote Spartacus for Kirk Douglas and Exodus for Otto Preminger. Both films aided in ending the blacklists, especially for Trumbo when he was given full credit. Acceptance came more slowly for others and, in some instances, never.

He created many more screenplays, including Lonely Are the Brave (1962), starring Kirk Douglas. In 1970 Trumbo received the Laurel Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Screen Writers Guild. He wrote and directed the movie adaptation of Johnny Got His Gun and created his last screenplay, Papillon. The year the final movie came out, he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

On September 10, 1976, Trumbo died at age seventy of a heart attack. Recognition eventually reached him, however. In 1975 the academy, which had previously endorsed the blacklist, awarded Trumbo an Oscar for The Brave One and would do so posthumously for Roman Holiday eighteen years later.

Guilt by association and red-baiting have found new life in present-day politics. In the US government, McCarthyism wed the concept of “like Caesar’s wife, above reproach,” and their ugly child was the #MeToo movement used to sever tall poppies as needed. We dare not assume their childbearing is complete.

Trumbo showed TP virtues of courage, fortitude, justice, and selflessness.