Citigroup’s option volume was light on a recent Wednesday, until the session’s last 90 minutes when a wave of trades hit. These weren’t bets on the shares moving — rather, they were part of a long-dormant strategy that’s back in vogue thanks to the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes.

The trade involves selling large volumes of put options that allow the holder to offload shares far above the current market level, and collecting interest on the premium received. It was pointless back when interest rates were near zero. But now, with Treasury yields at 5% or more, the strategy is suddenly worthwhile.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

“Nobody did this for 20 years because there wasn’t any interest rates,” said Joe Mazzola, director of trading and education at Charles Schwab & Co. “Interest rates are back. It makes sense.”

The strategy is largely used by large institutional players “trading thousands at a time to make half a penny,” Mazzola said. “Mom and Pop don’t do this.”

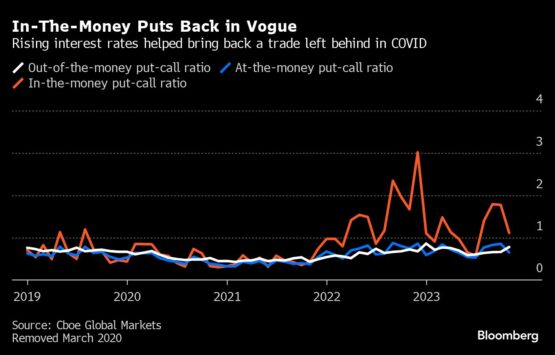

According to data from Cboe Global Markets, these financing trades are taking place twice as often as they did just three years ago. The exchange operator pointed to repeated rate tightening as one reason traders have dusted off their old playbooks.

It’s an example of how traders have adjusted — or readjusted — to a higher interest-rate environment after years of near-zero rates. While these low-risk, high-volume plays have little impact on the market’s daily moves, they are frequent enough now to at times distort one of the most common measures of equities sentiment, the put-call ratio, particularly when it comes to individual stocks.

Analysts often cite the put-call ratio as a gauge of investor caution, with higher volumes of puts signaling bearishness.

“The put-call ratio has spiked overall, but if you look at at-the-money, out-of-the-money options, you see it’s not doing anything,” said Henry Schwartz, global head of client engagement at Cboe. The deep-in-the-money puts “are inflating the volumes.”

Mechanics

Here’s how the trade appears to have gone on Nov. 8. Trader A bought 15,000 Citigroup Inc. $55 puts and sold the same number of $50 puts with Trader B, getting the right to sell shares at $55 and the obligation to buy them at $50.

US stock options are mostly “American-style,” meaning options buyers can exercise their rights any time before expiration. So on that same day, both traders exercise the options they bought, 72 days ahead of expiration. Seems pointless, right?

Perhaps not. Since there are other positions open in the $50 put Trader A sold, they may not have to buy all those shares. Options assignment happens randomly through the exchange, so even though Trader B exercised their position, other options holders have not.

The higher the open interest for a given contract, the greater the odds of not being assigned. In this case, the $55 and $50 puts had 12 000 and 20 600 contracts outstanding, respectively, before the trade.

Trader A can earn interest on that premium until they’re eventually assigned the option. With three-month Treasury bills yielding some 5.3% when the trade took place, that could be as much as $160 000 if the options aren’t assigned until expiry, barring major moves in the shares that bring the options back into play.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

“Higher interest rates mean that the gain for the put seller from the long option holder not optimally exercising is higher. So instead of, say, making 1/100th of a cent per day per contract — basically nothing — it’s possible to make one cent per day per contract,” said John Zhu, head of US trading at market making firm Optiver. “If done enough times, then it’s possible to make some money from that.”

Wednesday trading

One other quirk: These trades generally happen on Wednesday. Since options that are exercised take two days to settle, a contract exercised mid-week will settle on Friday, providing the entire weekend of funding, according to Alex Kosoglyadov, managing director of equity derivatives at Nomura Securities International. For that reason, put-call ratios mid-week might be particularly distorted, he said.

Another trigger for the trade is declining stock valuations. Data from Cboe shows that the trade bounced back in 2022 and then faded at the beginning of 2023 amid an unexpected tech-led rally. According to Cboe’s Schwartz, sinking share prices lead to high open interest on the deep in-the-money contracts.

Some choose not to exercise due to “transaction costs and tax considerations,” Schwartz said. “It’s so deep in the money that it’s not really much of an option anymore. It’s just holding the money.”

There’s reason to believe the trade might continue in 2024. The market is full of optimism that the Fed will lower rates, but borrowing costs will stay elevated for some time, providing ample opportunity to pick up a bit of extra cash.

According to Steve Sosnick, chief strategist at Interactive Brokers, the strategy does not generally occur in other countries and results from quirks in US-trading rules. It’s unlikely that will change anytime soon.

“Those who engage in the practice fight hard to keep it,” he said. “It’s hard to discern how the general public is affected by it.”

© 2024 Bloomberg