For the global wealthy with money to hide, it has long been helpful to have a Swiss company at your side. One with a nameplate, a letter-box, and no employees.

But like banking secrecy over a decade ago, the Swiss shell-company industry is now facing a fundamental threat. In its fight against money laundering, the government is now pursuing a draft law that would force firms to declare their true owners and attorneys to speak up about suspect transactions.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

The changes would go some way to answering Switzerland’s international critics including the US government and the OECD, who’ve been saying for years that the country is out of step with a stronger global push to rein in tax evasion and stem flows of dirty money. Despite the traditions of discretion and secrecy, support is building to enact such far-reaching changes.

“Banks face a duty of due diligence, so why don’t lawyers as well?” says Katia Villard, a professor of law at the University of Geneva. “Some lawyers, not all, have abused this privilege and so the law is targeting them.”

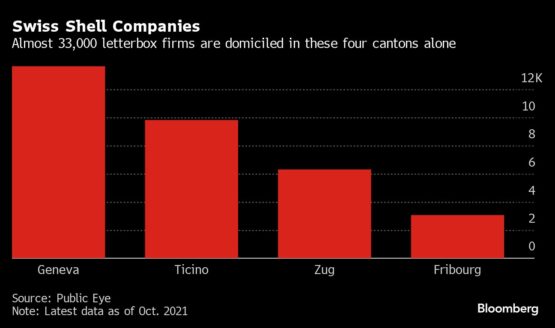

At last count, there were close to 33 000 shell companies based in Switzerland, according to a 2021 survey by NGO Public Eye. Geneva is the leading location, with an estimated one letterbox firm for every 37 citizens in the canton.

The government is targeting lawyers who help set up companies and purchase real estate for clients as being at particularly high risk of being caught up in illegal activity. The new law, if it passes, would require lawyers to report any suspicious financial transactions that they encounter to the Swiss money-laundering office. Those not following the new law in general face fines of as much as 500 000 Swiss francs ($570 730).

But having been spared the same kind of anti-money-laundering measures that the financial sector has dealt with for years, the legal industry is readying for a fight back. Lawyers say the draft law is both guilty of over-reach and that it is vague. A potential loophole exists in the fact that the precise point at which an attorney is covered by attorney-client privilege is not defined clearly enough, they say.

And rather than targeting just the fringe of shady lawyers, this would also encompass the regular businesses of property and M&A law, argues Miguel Oural, a partner at Lenz & Staehelin and chairman of the Geneva Bar Association.

“Besides this unacceptable stab at professional secrecy, the envisaged legislation has so broad a scope of application that corporate, commercial or real estate lawyers, who account for a very substantial part of the work of law firms, will face an unbearable amount of new, very complicated and time-consuming compliance work,” says Oural.

The Swiss Lawyers’ Association declined to comment, saying it will publish a position paper.

The government has also underestimated the difficulty of implementing and enforcing the law, according to Shahram Dini, a lawyer and president of the Geneva Lawyers’ Supervisory Board. It’s the main legal oversight body across the city but has a staff of fewer than 10 to oversee Geneva’s 2 700 lawyers.

“The canton needs to give us the resources: either the controls are done by us and the canton gives us the money or the canton refuses and a federal inspector comes and does this,” he says. “It’s the choice between bad or worse.”

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

‘Lacks clarity’

Switzerland’s efforts are an attempt to align with the global push to close tax loopholes and reduce money laundering. And there has been some success — offshore tax evasion has declined by a factor of three over the last decade, according to the EU Tax Observatory. A proposed European Union rule to crack down on shell companies aims to ensure firms have a real economic purpose, though that initiative is still a way off from becoming law in countries across the bloc.

The OECD’s Financial Action Task Force urged Switzerland in a 2016 evaluation to extend its existing anti-money laundering laws to include the creation of legal entities, including shell companies. An October report by the FATF said Switzerland had made progress in combating money laundering but was still only “partly compliant” with regard to due diligence by lawyers.

Even the Swiss Parliament’s main oversight committee is not happy with the proposed law. It issued a statement last month saying that “the scope of the obligation to declare lacks clarity and raises questions as to its relationship with the provisions of the penal code on professional secrecy.”

When the government took a first stab at tightening the rules in 2021, objection from the many lawyers in the Swiss parliament helped to torpedo the reforms. This time the government has tried to take their reservations into account and has narrowed the original scope of the bill to riskier activities, including legal advice for the creation of companies or purchasing a property.

Whether that’s enough for the reform to pass will become clear when lawmakers debate the bill next year.

Fifteen years ago, Swiss bankers who were used to light-touch regulation complained that ‘onerous’ new compliance rules would make them less competitive. Lawyers will similarly just have to get used to asking more of their clients, says the University of Geneva’s Villard.

“At first banks said ‘we will lose our clients’ but are now used to it.”

© 2023 Bloomberg