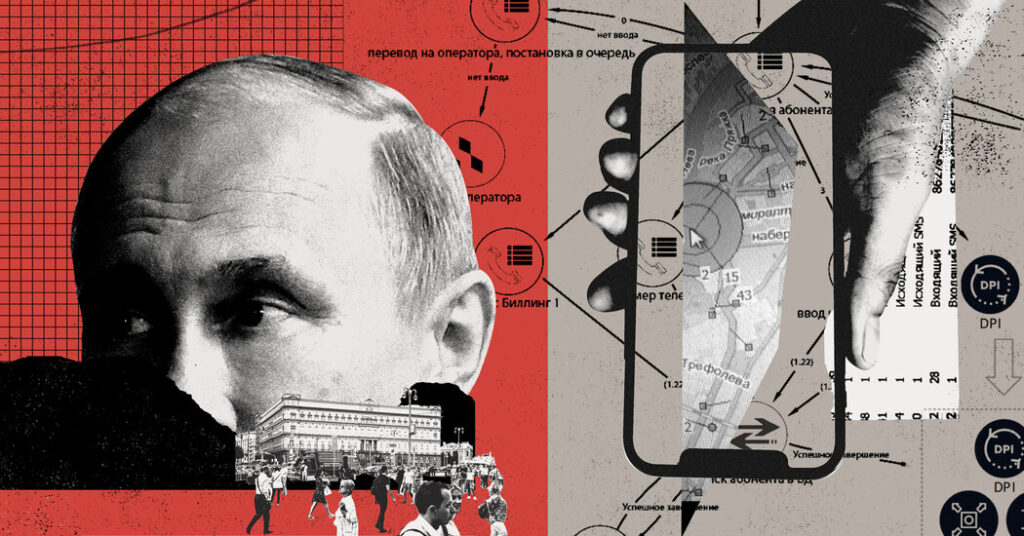

As the war in Ukraine unfolded last year, Russia’s best digital spies turned to new tools to fight an enemy on another front: those inside its own borders who opposed the war.

To aid an internal crackdown, Russian authorities had amassed an arsenal of technologies to track the online lives of citizens. After it invaded Ukraine, its demand grew for more surveillance tools. That helped stoke a cottage industry of tech contractors, which built products that have become a powerful — and novel — means of digital surveillance.

The technologies have given the police and Russia’s Federal Security Service, better known as the F.S.B., access to a buffet of snooping capabilities focused on the day-to-day use of phones and websites. The tools offer ways to track certain kinds of activity on encrypted apps like WhatsApp and Signal, monitor the locations of phones, identify anonymous social media users and break into people’s accounts, according to documents from Russian surveillance providers obtained by The New York Times, as well as security experts, digital activists and a person involved with the country’s digital surveillance operations.

President Vladimir V. Putin is leaning more on technology to wield political power as Russia faces military setbacks in Ukraine, bruising economic sanctions and leadership challenges after an uprising led by Yevgeny V. Prigozhin, the commander of the Wagner paramilitary group. In doing so, Russia — which once lagged authoritarian regimes like China and Iran in using modern technology to exert control — is quickly catching up.

“It’s made people very paranoid, because if you communicate with anyone in Russia, you can’t be sure whether it’s secure or not. They are monitoring traffic very actively,” said Alena Popova, a Russian opposition political figure and digital rights activist. “It used to be only for activists. Now they have expanded it to anyone who disagrees with the war.”

The effort has fed the coffers of a constellation of relatively unknown Russian technology firms. Many are owned by Citadel Group, a business once partially controlled by Alisher Usmanov, who was a target of European Union sanctions as one of Mr. Putin’s “favorite oligarchs.” Some of the companies are trying to expand overseas, raising the risk that the technologies do not remain inside Russia.

The firms — with names like MFI Soft, Vas Experts and Protei — generally got their start building pieces of Russia’s invasive telecom wiretapping system before producing more advanced tools for the country’s intelligence services.

Simple-to-use software that plugs directly into the telecommunications infrastructure now provides a Swiss-army knife of spying possibilities, according to the documents, which include engineering schematics, emails and screen shots. The Times obtained hundreds of files from a person with access to the internal records, about 40 of which detailed the surveillance tools.

One program outlined in the materials can identify when people make voice calls or send files on encrypted chat apps such as Telegram, Signal and WhatsApp. The software cannot intercept specific messages, but can determine whether someone is using multiple phones, map their relationship network by tracking communications with others, and triangulate what phones have been in certain locations on a given day. Another product can collect passwords entered on unencrypted websites.

These technologies complement other Russian efforts to shape public opinion and stifle dissent, like a propaganda blitz on state media, more robust internet censorship and new efforts to collect data on citizens and encourage them to report social media posts that undermine the war.

They add up to the beginnings of an off-the-shelf tool kit for autocrats who wish to gain control of what is said and done online. One document outlining the capabilities of various tech providers referred to a “wiretap market,” a supply chain of equipment and software that pushes the limits of digital mass surveillance.

The authorities are “essentially incubating a new cohort of Russian companies that have sprung up as a result of the state’s repressive interests,” said Adrian Shahbaz, a vice president of research and analysis at the pro-democracy advocacy group Freedom House, who studies online oppression. “The spillover effects will be felt first in the surrounding region, then potentially the world.”

Beyond the ‘Wiretap Market’

Over the past two decades, Russian leaders struggled to control the internet. To remedy that, they ordered up systems to eavesdrop on phone calls and unencrypted text messages. Then they demanded that providers of internet services store records of all internet traffic.

The expanding program — formally known as the System for Operative Investigative Activities, or SORM — was an imperfect means of surveillance. Russia’s telecom providers often incompletely installed and updated the technologies, meaning the system did not always work properly. The volume of data pouring in could be overwhelming and unusable.

At first, the technology was used against political rivals like supporters of Aleksei A. Navalny, the jailed opposition leader. Demand for the tools increased after the invasion of Ukraine, digital rights experts said. Russian authorities turned to local tech companies that built the old surveillance systems and asked for more.

The push benefited companies like Citadel, which had bought many of Russia’s biggest makers of digital wiretapping equipment and controls about 60 to 80 percent of the market for telecommunications monitoring technology, according to the U.S. State Department. The United States announced sanctions against Citadel and its current owner, Anton Cherepennikov, in February.

“Sectors connected to the military and communications are getting a lot of funding right now as they adapt to new demands,” said Ksenia Ermoshina, a senior researcher who studies Russian surveillance companies with Citizen Lab, a research institute at the University of Toronto.

The new technologies give Russia’s security services a granular view of the internet. A tracking system from one Citadel subsidiary, MFI Soft, helps display information about telecom subscribers, along with statistical breakdowns of their internet traffic, on a specialized control panel for use by regional F.S.B. officers, according to one chart.

Another MFI Soft tool, NetBeholder, can map the locations of two phones over the course of the day to discern whether they simultaneously ran into each other, indicating a potential meeting between people.

A different feature, which uses location tracking to check whether several phones are frequently in the same area, deduces whether someone might be using two or more phones. With full access to telecom network subscriber information, NetBeholder’s system can also pinpoint the region in Russia each user is from or what country a foreigner comes from.

Protei, another company, offers products that provide voice-to-text transcription for intercepted phone calls and tools for identifying “suspicious behavior,” according to one document.

Russia’s enormous data collection and the new tools make for a “killer combo,” said Ms. Ermoshina, who is also a senior researcher at the Center for Internet and Society, part of the French National Center for Scientific Research. She added that such capabilities are increasingly widespread across the country.

Citadel and Protei did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesman for Mr. Usmanov said he “has not participated in any management decisions for several years” involving the parent company, called USM, that owned Citadel until 2022. The spokesman said Mr. Usmanov owns 49 percent of USM, which sold Citadel because surveillance technology was never within the firm’s “sphere of interest.”

VAS Experts said the need for its tools had “increased due to the complex geopolitical situation” and volume of threats inside Russia. It said it “develops telecom products which include tools for lawful interception and which are used by F.S.B. officers who fight against terrorism,” adding that if the technology “will save at least one life and people well-being then we work for a reason.”

No Way to Mask

As the authorities have clamped down, some citizens have turned to encrypted messaging apps to communicate. Yet security services have also found a way to track those conversations, according to files reviewed by The Times.

One feature of NetBeholder harnesses a technique known as deep-packet inspection, which is used by telecom service providers to analyze where their traffic is going. Akin to mapping the currents of water in a stream, the software cannot intercept the contents of messages but can identify what data is flowing where.

That means it can pinpoint when someone sends a file or connects on a voice call on encrypted apps like WhatsApp, Signal or Telegram. This gives the F.S.B. access to important metadata, which is the general information about a communication such as who is talking to whom, when and where, as well as if a file is attached to a message.

To obtain such information in the past, governments were forced to request it from the app makers like Meta, which owns WhatsApp. Those companies then decided whether to provide it.

The new tools have alarmed security experts and the makers of the encrypted services. While many knew such products were theoretically possible, it was not known that they were now being made by Russian contractors, security experts said.

Some of the encrypted app tools and other surveillance technologies have begun spreading beyond Russia. Marketing documents show efforts to sell the products in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, as well as Africa, the Middle East and South America. In January, Citizen Lab reported that Protei equipment was used by an Iranian telecom company for logging internet usage and blocking websites. Ms. Ermoshina said the systems have also been seen in Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine.

For the makers of Signal, Telegram and WhatsApp, there are few defenses against such tracking. That’s because the authorities are capturing data from internet service providers with a bird’s-eye view of the network. Encryption can mask the specific messages being shared, but cannot block the record of the exchange.

“Signal wasn’t designed to hide the fact that you’re using Signal from your own internet service provider,” Meredith Whittaker, the president of the Signal Foundation, said in a statement. She called for people worried about such tracking to use a feature that sends traffic through a different server to obfuscate its origin and destination.

In a statement, Telegram, which does not use end-to-end encryption on all messages by default, also said nothing could be done to mask traffic going to and from the chat apps, but said people could use features it had created to make Telegram traffic harder to identify and follow. WhatsApp said in a statement that the surveillance tools were a “pressing threat to people’s privacy globally” and that it would continue protecting private conversations.

The new tools will likely shift the best practices of those who wish to disguise their online behavior. In Russia, the existence of a digital exchange between a suspicious person and someone else can trigger a deeper investigation or even arrest, people familiar with the process said.

Mr. Shahbaz, the Freedom House researcher, said he expected the Russian firms to eventually become rivals to the usual purveyors of surveillance tools.

“China is the pinnacle of digital authoritarianism,” he said. “But there has been a concerted effort in Russia to overhaul the country’s internet regulations to more closely resemble China. Russia will emerge as a competitor to Chinese companies.”