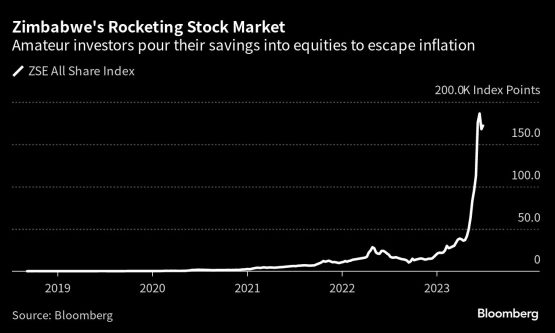

In Harare, Zimbabwe, home to the world’s biggest stock market rally, the gains come at break-neck speed: 5%, 10%, even 20% in a single session. Tally them up, and the market is up an astonishing 800% on the year.

But in a country where up is often down and the next currency crisis is always just around the corner, the furious rally is a cause for concern, not jubilation. It’s a tell-tale sign, market observers here say, that investors are bracing for an inflation spiral and seeking a hedge to protect the value of their money. Consumer prices are climbing at an annual pace of over 100%, sparking jitters in a nation where the scars of hyperinflation run deep.

The stock market may be tiny — total capitalization is $1.8 billion, dwarfed by neighbouring South Africa’s $1 trillion-plus bourse — but at least it’s a place where locals can easily invest. And, with the Zimbabwe dollar plummeting almost daily, few businesses will accept it as payment on any major purchase — property, cars, even fuel.

“So all of those Zimbabwe dollars will go into the equities market,” said Tatenda Nemaungwe, a stock trader in Harare. Nemaungwe, 36, quit as a personal financial adviser five years ago to manage his own portfolio. “I was riding a dead horse.” In an average month, he now earns more than 10 times his old salary of $1 500 thanks to what he calls an “unending bull run.”

Zimbabwe stocks have easily out-sprinted 2023’s other big gainers. Argentina’s Merval index has merely doubled, while S&P 500 investors must be content with a 16% rally. Given the country’s economic ills, foreigners have largely abandoned the Zimbabwe equity market and account for just 15% of trading. Turnover is a fraction of major exchanges at about $650 000 a day, compared with $240 billion in combined dealings in the Wall Street benchmark.

Established in 1894, the Zimbabwe exchange is among Africa’s oldest. Its home in the upmarket Harare suburb of Highlands, popular with diplomats and affluent retirees because of its smart residences in leafy and well-maintained streets, contrasts with the raucous bustle of the capital’s downtown. A contrast, too, with the mayhem playing out on its trading board.

That price action has attracted about 23 000 retail investors, including Simba Nyamadzawo, who made his first trade in October using his mobile phone. “I am here for profit,” the 35-year-old said.

Harare stock pickers have a universe of 55 companies to choose from. The most popular are the blue chips — like drinks maker Delta Corp., telecoms provider Econet Wireless Zimbabwe and mobile money group EcoCash Holdings Zimbabwe.

They are among the exchange’s most liquid stocks, companies that provide products and services Zimbabweans rely upon. That buttresses their sales and earnings, even in times of eye-watering inflation. “Delta is tried and tested,” is how Nyamadzawo summed it up.

It hasn’t been a straight path higher. A fit of currency weakness in May wiped out 84% of the local dollar’s value — and half of Nyamadzawo’s fledgling portfolio. But the exchange-rate induced swoon was just a temporary setback and he is buying more stocks ahead of what he sees as the trigger for the next bull run: August’s general elections.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa is facing off against a fractured opposition field of 10 candidates and Zimbabwe has a history of disputed votes since white-minority rule ended in 1980. Mnangawa’s government is blamed for much of the economic turmoil that has driven inflation to 176% as of June. The largest local banknote — the 100 Zimbabwe dollar bill — is not enough to pay for a single tomato. The central bank’s main lending rate is the world’s highest, at 150%.

“People tend to hesitate about making important decisions in the election run-up,” Nyamadzawo said. “As soon as the election is over, people will want to buy once again.”

Foreign investors are unlikely to be enticed to the Harare market by the latest rally, according to Hasnain Malik, who covers emerging and frontier markets at Tellimer, a Dubai-based research firm. The gains are “driven entirely by the search for a hedge against inflation and a tradable security for local investors, who have little faith in the local currency and cannot easily access US dollars,” he says.

For locals, there’s a worry that regulators will put an end to the stock-market party. Back in 2020, authorities shut down the exchange for five weeks, complaining that speculation in stocks with overseas listings was undermining the Zimbabwe dollar. Exchange Chief Executive Officer Justin Bgoni declined to comment on this year’s bull run.

Nyamadzawo doesn’t plan to push his luck too far. “If I put my money in today and make a profit tomorrow, I will move it out.” It’s hard to predict the future when the economy is so volatile, he says. “I am not sticking around for five years.”

© 2023 Bloomberg