In mid-May, CNN reported that the U.S. intelligence neighborhood was about to start a sweeping evaluate of the manner it does enterprise. What prompted the senior officers to motion? The reply is straightforward sufficient: alarmingly inaccurate predictions as to the sturdiness of the U.S. supported authorities of Afghanistan, which led to a decidedly ignominious withdrawal of our forces there, in addition to overly pessimistic projections of Ukraine’s capability to stave off a serious assault by the Russian military.

In view of the gravity of these errors, this appears a crucial and laudable enterprise. But… don’t anticipate the evaluate and inevitable record of suggestions to enhance the difficult means of gathering, analyzing, and consuming intelligence merchandise by a lot. So say two of the main students of intelligence in the English talking world, Richard Betts and the late Robert Jervis, each of Columbia University’s political science division. After many years of finding out the query, these males have concluded that invariably the suggestions of commissions designed to enhance the caliber of the intelligence course of after American wars have a tendency to produce a brand new set of issues. As Betts put it in a widely quoted essay on this subject:

Curing some pathologies with organizational reforms typically creates new pathologies or resurrects previous ones; perfecting intelligence manufacturing doesn’t essentially lead to perfecting intelligence consumption; making warning programs extra delicate reduces sensitivity; the rules of optimum analytic process are in some ways incompatible with the imperatives of the decision-making course of; avoiding intelligence failure requires the elimination of strategic preconceptions, however leaders can’t function purposefully with out some preconceptions. In devising measures to enhance the intelligence course of, policymakers are damned in the event that they do and damned in the event that they don’t.

Strategic intelligence, which Betts properly defines with admirable economic system as “the acquisition, analysis, and appreciation for relevant data,” is an especially difficult enterprise. It’s a novel amalgam of science and artwork, for it invariably includes political and psychological elements which are distinctive to a given battle, and topic to abrupt change. And it should not be forgotten that senior intelligence officers have to promote their product properly whether it is to carry actual weight with customers, and that’s a completely separate ability than producing good evaluation.

Of course, severe college students of latest American army historical past have already got a fundamental understanding of what went incorrect in assessments of the last section of the Afghan tragedy, and in the first section of the Russia-Ukraine War. Broadly talking, the American intelligence neighborhood—the 18 companies concerned in its assortment , together with the chief customers, the White House and the National Security Council—have change into overly depending on quantitative evaluation derived primarily from technical and digital sources (sign intelligence), at the expense of each human intelligence (brokers and sources on web site in the enviornment of battle) and experience about the political dynamics and cultural histories of international societies.

What Clausewitz referred to as ethical, or religious, elements in his masterwork, On War—the will to struggle amongst the troopers of a military, the stage of widespread help for the authorities, the creativity and instinct of the political leaders of the adversaries—these are issues that Clausewitz says “cannot be classified or counted. These have to be seen and felt.”

On paper, the American-trained Afghan Army of greater than 300,000 troops, armed with much more subtle weapons than the Taliban, together with drones and jet fighters, ought to have been ready to maintain off the last offensive Taliban onslaught properly into 2022. That didn’t occur, as a result of aside from some 30,000 Afghan Special Forces, the remainder of the “Army” had little interest in defending a authorities they and their households perceived to be corrupt, ineffectual, and in the pocket of the West. The majority of the Afghan Army models didn’t put up any resistance to the Taliban. They negotiated their very own give up or supplied no resistance in any way.

As for the CIA projections that the Russians would break the again of Ukrainian resistance in a matter of days, it’s clear that analysts relied an excessive amount of on their quantitatively-based evaluation of Russian models and weapons programs, whereas their grasp of Clausewitz’s “moral factors” on each side was shaky, at greatest.

One of the most vital failures in U.S. intelligence since Vietnam was the neighborhood’s lack of ability to get a grip on the swirling political and army developments surrounding the Iranian Revolution of 1979. In February of that 12 months, a weird assortment of liberal reformers, leftists, and Muslim fundamentalist clerics overthrew the Shah of Iran, at the time the United States’ strongest ally in the Middle East and a bulwark towards Soviet expansionism. Led by a glowering, mysteriously charismatic cleric, Ayatollah Khomeini, the clerics deftly outmaneuvered and marginalized their revolutionary allies, and established the world’s first trendy Islamic Republic.

“The Carter administration’s responses to developments in Iran was halting, contradictory, and in the opinion of every serious historian of U.S. relations of whom I’m aware, depressingly inept.”

Anti-Americanism had been the glue that stored collectively the disparate factions of resistance to the Shah’s rule. All the revolutionaries believed that the Shah, whose regime had change into more and more oppressive and corrupt, was in the pocket of Washington. Washington fully misinterpret the dynamics of Iranian politics. Less than a 12 months earlier than the Shah was ousted, President Jimmy Carter had praised the Shah lavishly, calling his regime “an island of stability in a turbulent corner of the world.” The turbulence and rising tide of anti-Americanism in Iran had been in plain sight for a number of years, however the American intelligence neighborhood had developed no contacts amongst the myriad opposition teams and depended closely on the Shah’s intelligence companies. They instructed the Americans not what was actually happening, however what the Shah needed the Americans to know.

The Carter administration’s responses to fast-moving developments in Iran earlier than and after that occasion, together with the notorious hostage disaster of 444 days, was halting, contradictory, and in the opinion of each severe historian of U.S. relations of whom I’m conscious, depressingly inept. Among the U.S. intelligence neighborhood, opines the famous army historian Lawrence Freedman in his historical past of U.S coverage in the Middle East, A Choice of Enemies, “there was little grasp of the inside energy struggles that have been quickly underway in Tehran. The diplomats and intelligence specialists despatched to attempt to choose up the items of U.S.-Iranian relations lacked any experience in the ideological wellsprings of the Islamic motion… Because clerics weren’t typically identified for his or her lust for energy or their urge for food for presidency, the comforting assumption was that their position would quickly be circumscribed by correct politicians.”

Professors Betts and Jervis join a wide consensus of scholars in believing that the most egregious intelligence failures in recent American history lie more with the top-level consumers of intelligence than with the CIA or the other myriad organizations involved in its collection and analysis. Here, the chief villains, writes Betts, are “wishful thinking, disregard of professional analysis, and the preconceptions of consumers.” There was nothing impulsive about the series of decisions that committed the United States to fighting a major war in Vietnam, and then prolonged America’s commitment to winning that conflict, even as signs of failure began to accumulate like buzzards around a corpse.

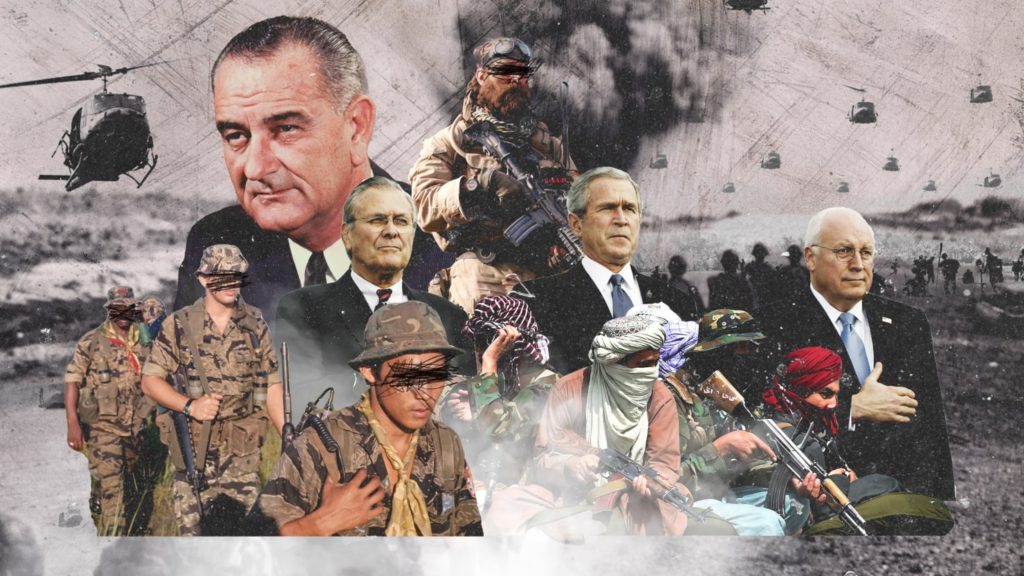

Between 1950 and the summer of 1965, three U.S. presidents opted to expand America’s involvement in Vietnam, despite that ancient Asian country’s seeming irrelevance to American vital interests, and the extraordinary level of dysfunction and corruption among America’s Vietnamese allies. Had President Johnson heeded the CIA’s pessimistic reports about American prospects in Vietnam, he never would have committed the country to a major ground war.

While the Johnson administration’s “best and the brightest” justified America’s growing military presence in Southeast Asia as a proper response to “wars of nationwide liberation” sponsored by the Kremlin and Beijing, the CIA consistently pointed out that this was simply not the case. Hanoi ran its own show, deftly playing off one communist superpower against the other, and frequently decided to go its own way in the prosecution of the war effort against the Americans. The Agency’s doubts about the trajectory of American policy in the war were especially pronounced during late 1964 and early 1965, when the Johnson administration crossed the Rubicon by deploying American combat units to take the fight to the enemy in the South in March 1965. In effect, Johnson took over management of the war from the South Vietnamese and put it in the hands of his own generals.

Here is a brilliantly prescient assessment by CIA analyst Harold P. Ford, written in April 1965, just as LBJ was committing American Marines to offensive operations for the first time:

This troubled essay proceeds from a deep concern that we are becoming progressively divorced from reality in Vietnam, that we are proceeding with far more courage than wisdom—toward unknown ends… There seems to be a congenital American disposition to underestimate Asian enemies. We are doing so now. We cannot afford so precious a luxury. Earlier, dispassionate estimates, war games, and the like, told us that [the communists in Vietnam] would persist in the face of such pressures as we are now exerting on them. Yet we now seem to expect them to come running to the conference table, ready to talk… The chances are considerably better than even that the United States will in the end have to disengage from Vietnam, and do so considerably short of our present objectives.

Johnson ignored Mr. Ford’s sage advice. Within weeks of receiving this report, he approved General Westmoreland’s three-phase plan to win the war by 1968 through a strategy of attrition. Using as many as half a million U.S. troops, he would destroy the enemy’s main forces with massive “search and destroy” sweeps, using American mobility and firepower to vanquish an enemy without any air power whatsoever, and little motorized transport. Westmoreland would pay lip service to the CIA’s belief that the war had to be fought and won in the villages, but he’d fight and win in the traditional American way: conventional warfare, emphasizing air power and artillery, even though American military operations inflicted massive destruction on the people America had come to South Vietnam to “save.”

Why did America’s policy makers dismiss the astute counsel of the CIA’s wise men? The short answer is that they couldn’t break free of the domino theory—the false notion that if one state fell to communism, a string of others was sure to follow, and that this would lead to an irreversible loss of credibility and prestige for the United States… and for Lyndon Johnson and his senior advisers.

“

The disastrous determination by the Bush administration to invade Iraq grew out of a refusal to hear to good intelligence.”

One of the most delicate and perceptive of the CIA analysts, George W. Allen, places it properly in his guide, None So Blind: “America failed in Vietnam not because intelligence was lacking, or wrong, but because it was not in accord with what its consumers [i.e., Ike, JFK, LBJ, and their chief advisers] wanted to believe, and because its relevance was outweighed by other factors in the minds of those who made national security policy decisions.”

The disastrous determination by the Bush administration to invade Iraq grew out of a refusal to hear to good intelligence evaluation as properly. From the spring of 2002 ahead, Bush joined with Cheney, Rumsfeld, and several other different influential hawks in marginalizing a really substantial physique of intelligence and evaluation from inside and outdoors the authorities indicating that an invasion of Iraq may properly create extra issues for the United States, Iraq, and the whole Middle East than it could resolve.

This, a minimum of, was the thought of impression of no much less a determine than Richard Dearlove, the head of Britain’s equal of the CIA, MI6, who engaged in top-secret discussions with the American president and his principal advisers in early July 2002.

A abstract of Dearlove’s testimony about these conferences was recorded in a top-secret Downing Street memo: “There was a perceptible shift in attitude. Military action was now seen as inevitable. Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy. The NSC had no patience with the UN route [of diplomatic pressure] . . . There was little discussion in Washington of the aftermath of military action.”

Indeed, the most dependable and goal accounts now we have of the administration’s deliberations agree totally with Dearlove’s assertions that the intelligence and information have been being manipulated to match the administration’s coverage inclinations, and that there was treasured little dialogue of the possible aftermath of reducing the head off the snake in Iraq.

In its secret discussions throughout the planning section and in its public protection of the mission, the administration aggressively “worst-cased” the risk posed by Saddam, and “best-cased” the outcomes of eradicating him from energy.

A four-star basic who labored on the struggle plan for months instructed army author Tom Ricks that he felt the president was shielded from the recommendation of these in the higher ranks of the army who thought the United States was heading right into a quagmire each earlier than and after the invasion commenced. That recommendation, he mentioned, was “blown off by the president’s key advisers… the people around the president were so, frankly, intellectually arrogant. They knew that postwar Iraq would be easy and would be a catalyst for change in the Middle East. They were making simplistic assumptions and refused to put them to the test.”

The CIA and State Department analysts have been far, far much less sanguine about what may occur because of the invasion than Rumsfeld, Cheney, and the different hawks. According to Paul Pillar, the prime CIA coordinator for intelligence on Iraq from 2001 to 2005, the skilled intelligence neighborhood offered an image of a political tradition in Iraq that might not present fertile floor for democracy and foretold a protracted, tough, turbulent transition.

It projected {that a} Marshall Plan-type effort can be required to restore the Iraqi economic system, regardless of Iraq’s considerable oil assets.

It forecast that in a deeply divided Iraqi society, with Sunnis resentful over their lack of their dominant place and Shiites looking for energy commensurate with their majority standing, there was a major likelihood that the teams would interact in violent battle until and occupying energy prevented it.

And it anticipated {that a} international occupying power would itself be the goal of resentment and assaults—together with by guerrilla warfare—until it established safety and put Iraq on the street to prosperity in the first few weeks or months after the fall of Saddam… War and occupation would increase political Islam and enhance sympathy for terrorists’ targets—and Iraq would change into a magnet for extremists from elsewhere in the Middle East.

The coverage implications of “the entire body of official intelligence analysis,” mentioned Pillar, was to keep away from struggle, or “if war was going to be launched, to prepare for a messy aftermath.”

Vietnam and Iraq, in fact, have been basically irregular, or uneven conflicts. Far greater than standard conflicts, irregular wars are formed extra by politics and political group amongst the individuals than by army operations. Since Vietnam, America’s senior international coverage determination makers have a really unlucky behavior of forgetting this basic reality. They have been overly enamored by the energy of the U.S. army machine, however obtuse in failing to acknowledge the limits of army energy alone to form politics in international societies.

This tendency goes far in explaining why the United States retains dropping wars.