[MUSIC PLAYING]

Russia invaded Ukraine 15 months ago. For a time following the invasion, it was all the world could talk about. It’s all the show could talk about. And now, as happens with a lot of stories huge at the outset, now the Russia-Ukraine war is treated as one news story — I mean, a major one — but one news story among many.

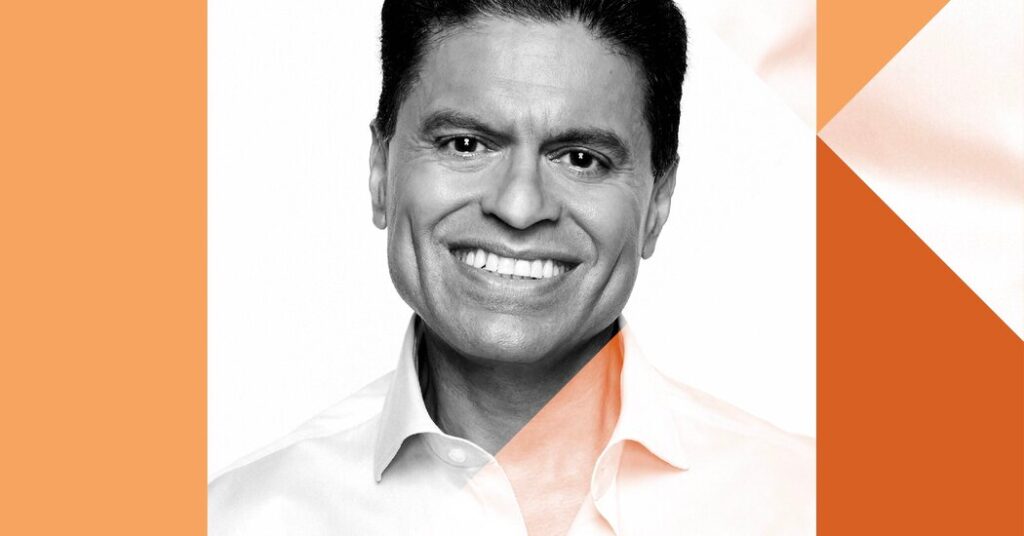

But it’s still more than that. It’s a kind of hyper story. There is the conflict itself, which matters enormously. And then there’s the way it’s reshaping global geopolitics and the relationships and balancing of the great powers. Early in the invasion, I had Fareed Zakaria on to talk about the way it felt at that moment like we were re-entering an age of great power conflict. So I wanted to have him back on now to discuss where the war is now, what the prospects and possibilities of its end might be, and how it’s changed the relationships and competition between America and Europe and China and India among others.

Zakaria, of course, is host of the CNN show, “Fareed Zakaria GPS.” He’s a columnist for The Washington Post and the author of many, many books, including, most recently “10 Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World.” As always, my email for our guest suggestions, thoughts, et cetera, ezrakleinshow@nytimes.com.

Fareed Zakaria, welcome back to the show.

Always a pleasure, Ezra.

So we last talked on the show in March 2022. This was right after Russia invaded Ukraine. So give me your overview of where that conflict stands now.

I think I said this to you the last time, but it’s worth pointing out that what this represents is two things, the Russian invasion of Ukraine. First, it is the most frontal challenge to the post-Cold War world order created sort of serendipitously and partly by design by the United States largely after the collapse of communism, because, at that point, one of the things that was settled was the post-Soviet space.

And what Putin is, in a sense, doing is this is sort of buyer’s remorse on the part of the Russians. They were weak in the mid-1990s — I mean, amazingly weak. The Russian economy had contracted by 50 percent between 1990 and 1996. That’s more than it had contracted during World War II. So Russia, at a moment of weakness, felt it gave up too much and is trying to, in a sense, claw back a piece of that, regardless of the fact that it violates international law, treaties that it’s signed, norms that have been established since 1945.

Relatedly, it is a sort of last gasp of the last multinational empire in the world. If you think about it, this is not so uncommon in terms of buyer’s remorse, in terms of empires not wanting to let go of what they see as defining their core colonies that in a sense define who they are. The Ukrainians don’t want to be part of Russia’s empire. And if there’s one trend line you see over the last 100 years, it’s nationalism. It’s the power of people, once they have decided that they want to live free. That is an unstoppable force. And that is what Russia is against.

I think the rest of it is honestly commentary in the sense that there will be day-to-day ups and downs, and the Russians will do well one month, and the Ukrainians will do well one month. But I think the secular trajectory is that Ukraine is going to be an independent nation.

It felt to me — and tell me if you think this is wrong — that I was hearing more about possible shapes of end games, of resolutions, of settlements a year ago than I am now. There’s a strange sense in which people seem to have settled in to a long, protracted war of attrition. Do you think that’s right? Is that what you feel in the commentary?

Yeah. I think you’re exactly right. And I think it’s probably for a few reasons. One is what we have realized is that neither side is strong enough to completely prevail, dominate, in this very quickly, yet neither side is so weak that they feel the need to capitulate. And that creates this dynamic where, as you say, it feels like this is going to be a long struggle.

I think it’s also fair to say what we have been surprised by is the absolutely implacable nature of Ukrainian nationalism. That people have realized, look, the Ukrainians are not going to give up. They are not going to give up easily. They are not going to settle for something that doesn’t feel like they have essentially maintained their independence. They’ve surprised on the battlefield on the upside.

So you put all that together, and I think you have a scenario where everyone is waiting for this Ukrainian counteroffensive. My guess is, as many people are saying, it will surprise on the upside as they have in the past. But I suspect it will not win the war. And that therefore, by the end of this year, you may begin to see a return to some of those conversations.

But because the conflict has become so dark, the Russians have done things that are really extraordinary, bombing civilian facilities and water treatment plants and hospitals, it’s difficult to imagine how these two sides come to an agreement, a settlement, recognize each other. I think this ends more like the Korean War, which technically hasn’t ended. It just is the two sides stopped fighting. There is a demilitarized zone between the two armies, which is exactly why it’s called the DMZ. But there’s never a peace treaty signed.

One dimension of the war that you hear, again, less about now than you did a year ago is the grip the Western sanctions have on the Russian economy. And early on, there was a sense that these were unexpectedly punishing. They began — the sense was they were maybe mild. Then very quickly, as Ukraine showed a ferocious level of resistance, they ramped up. Now, we were choking them off in the financial sector. There is certainly a sense that Russia is managing to limp along without the kind of punishing depression that would really put a lot of pressure on Putin.

I have two questions on this, but the first is, why are the sanctions underperforming?

It’s a great question. And there are two reasons I think. The first is we designed the sanctions so that Russia could continue to export energy. Russia could continue to sell oil and natural gas and also sells a lot of coal. And the reason is if Russian oil, natural gas and coal were completely shut out of the world markets, it would trigger a global recession. Oil would go to $200 a barrel, because all that Russian supply taken out of the market would mean that demand would vastly exceed supply. You would suddenly have huge price spikes. Much of the developed world would go into a recession, maybe even worse.

So we designed the sanctions to sort of force the Russians to have to sell at a discount, bid less than they could make. So they’re getting a lot of revenue. Russia is a huge exporter of energy, perhaps the world’s largest depending on how you count it. So that’s one part of it, which is an inevitable reality about Russia’s role in the world economy and in the energy economy.

The second — and I think this is the more unusual one — is there’s a big world economy out there now. We, I think, still have in our heads the idea that if the United States and Europe and Japan cut you off from the world economy, you’re done. But it turns out, about 50 percent of the world economy is now the so-called emerging markets. And they’re not abiding by the sanctions.

So the reports I’m getting from Russia that, for example, Starbucks has left, as did a thousand Western companies. But if you go to Russia and you go to the corner store where Starbucks was, there’s a coffee shop there. It’s called Star Coffee. It’s owned by Russians; they sell coffee for about the same price. I don’t know if it says good or bad. But many of those abandoned Western businesses have been taken over by Turkish businesses, Chinese businesses, Russian-owned businesses. So there’s a whole rest of the world economy out there that is still playing with Russia.

In fact, there’s some concern that the Russians are essentially evading the sanctions by importing things through Turkey, for example. The Turks buy something from the West. The Russians buy that same thing from Turkey. How do you prevent that?

All that said, the piece that has been very effective is the freezing of the central bank reserves and the denial of technology. It is absolutely clear that Russia is crippled by the lack of access to Western technology at the very high end, particularly of the digital economy, high-end computer chips, for example. It is a remarkably narrow funnel. You’re basically getting the stuff from three or four companies that do chip design, one company that does chip manufacturing, A.S.M.L. in Holland. And all those are essentially in the West-plus. What I call the West-plus, meaning the West plus Japan, South Korea, Singapore.

And so the hope, I think, in the West, at a certain point, was that these sanctions were going to be tight enough that Russia, if it couldn’t win quickly, it would not want to hold on slowly. Again, my sense is that’s not coming true. The sanctions are tough on them. They’re degrading their military, which is I think often an undernoticed important dimension of the sanctions. But the idea that they’re going to constrict enough to force Russia into settlement, because it can’t have this happen to them for three or four or five years, I don’t get the sense people are still optimistic about that.

Yeah. I think that this is one of the biggest flaws in the way we conduct international affairs ever since the end of the Cold War, which is we want to do something. We either don’t want to make the commitment, or we can’t make the commitment, or it’s too expensive or whatever to make the commitment to do something very dramatic, like military action. And so we do sanctions.

And they very rarely work in the sense that the regime in question changes its policy. In some cases, the sanctions are almost designed, even if not explicitly, to change the regime. And that certainly doesn’t happen.

We need to focus a little bit more on that central conundrum, which is sanctions tend to empower the regime in place.

Look at what the Iran sanctions have done. They have empowered the most conservative elements of Iran, the Revolutionary Guard, because they’re the guys that do all the smuggling. They’re the guys that have now control the key choke points which allow selective foreign goods in through medical exemptions or educational exemptions or whatever it is. It’s all the state. So you, in a sense, empower the state, and you disempower society, which are the broad forces that would be empowered by commerce, contact, capitalism.

And that dilemma proves to be very powerful. Look, there’s a famous story of Fidel Castro saying, I think, bizarrely to Sean Penn that if the Americans were to take the sanctions off, he would clamor for their reinstatement. The implication being the sanctions is what gives him a lot of his power and legitimacy that he’s standing up to the Americans.

Look at Venezuela. The sanctions there haven’t worked. Look at Iran, they haven’t worked. So we’re trying it with Russia. I don’t — I actually support the sanctions in Russia, because they do put pressure on the regime. But you’re not going to change Putin’s calculus. The only thing that can change Putin’s calculus is defeat on the battlefield.

And so in my mind, more important than the sanctions are give the Ukrainians all the weapons they need, give them all the training they need, do it fast and allow them to win on the battlefield, because, historically, that’s when countries do change course, when they’re bleeding soldiers and money on the battlefield.

So you predicted where I was going to go — there’s what we don’t give Russia and what we do give Ukraine. And we’ve drawn all kinds of lines and lines that have been moving about what we will and won’t give Ukraine in terms of armaments. They want more advanced technology, better fighter jets, et cetera. And we have consistently given them some of what they want and not all of what they want.

How would you describe the lines we’ve drawn? Why we drew them there, and whether drawing them there was wise?

So the administration is juggling something difficult. And I think they’re handling it pretty well, which is, you’re trying to do two things. You’re trying to support the Ukrainians, make sure that they have a tactical and strategic advantage as much as possible, make sure they have a kind of almost inexhaustible supply of things like ammunition and money. And the United States has, by far, been the most generous on both.

But at the same time, you’re trying not to trigger a conflict between Russia and NATO, between Russia, therefore, and the United States. This was a line we tried to tread very carefully during the Cold War. That’s why there were so many proxy wars in Central America and Southeast Asia, because the superpowers did not want to engage directly for fear that could lead to an inevitable nuclear escalation.

I think that’s a legitimate concern. I think the Biden people are thinking through that so seriously. And so some of the lines are they’re telling the Ukrainians, please do not use American weapons or use NATO weapons to attack Russia itself, attack Russian forces in Ukraine so that you are effectively repelling the invasion rather than invading Russia yourself. Obviously, the line is not perfect, but I think that’s a very sensible line.

Separately, there’s the issue of how much can the Ukrainian army absorb. If you talk to people in Washington, and these are people who I think are trying to do the right, thing they argue, look, there’s a limit to how fast the Ukrainians can learn to use the most sophisticated American weaponry, such as our advanced fighter jets, such as our best tank. And it does make some sense to make sure that those weapons are going to be used effectively before you give them.

So on the whole, I am not one of those people who thinks the Biden administration has been too slow, too little, too late. They’re trying to do it in a serious responsible way. Could it be 10 percent, 15 percent faster? Maybe, I don’t know. But I think in general they’re trying to balance the situation and have been doing it pretty well.

When I listen to what Ukrainian political leaders and world leaders are saying, though, the absolutely consistent, never-ending message is that they are not getting enough. So I take it that Washington says they’re doing plenty, but it’s also true that we’ve been changing what we’re giving them. And I don’t think that’s all about absorption capability. I mean, some of it we just thought or said — whether we thought it or not, I don’t know — that if we gave them this kind of weapon, Russia would take that as an escalation that might lead to a different kind of reprisal or a different kind of calculation from Putin.

And the argument I’ve heard about this is that not giving Ukraine the kind of advanced weaponry that could help them really win the war is not actually a way of deterring Putin. This idea that we’re going to balance this out when Russia actually has done the cross-border incursion and Russia actually does still have more manpower than Ukraine, that we are making a mistake in the calculus here, that Putin has already escalated, that he is already terrified of defeat. But allowing him to stay in this middle ground is allowing an extended equilibrium that just creates more constant danger as opposed to an actual resolution.

Look, if I were a Ukrainians I would be arguing, making exactly that case. And I would argue forcefully for more weapons sooner, as Winston Churchill argued passionately that the United States was not giving enough weaponry to Britain in ‘41 even. But the U.S. is a global power. This is not the only area it’s engaged in. It has to make sure that it has these broader strategic interests in mind.

I don’t get the sense that, as I say, they could — maybe there could have been some more sped-up version of what they’re doing. But I do think that concern about how far you go in terms of an outright invasion of Russia by a NATO-assisted force is a legitimate concern. I think that the Russians have not actually done as much as they could have done.

I mean, Russia has the largest nuclear arsenal in the world. It has a huge army. It has the capacity to do much more damage in Ukraine proper. Most of the damage they’ve done has been in the parts of Ukraine that they believe should be incorporated into Russia — the Donbas — and that band of Ukraine. They could unleash much more havoc on Ukraine itself. Now, they would pay a huge price. But I don’t think it’s fair to say that the Russians have done everything they can. In fact, that’s what scares me. I think the Russians could go up this escalation chain.

There is a sense early in the war that this was leading to, not just a newly united West, but in particular a United Europe led by a more muscular Germany. There’s a lot of excitement that Germany was not just funding Ukraine, but also saying it was going to spend a lot more on its own defense. Has that vision of a stronger Europe led by a more assertive Germany panned out?

Absolutely. I think that the thing that has always kept NATO vital is the sense of a real threat. At the end of the day, alliances cannot operate in a vacuum. And after the Cold War, there really was this sense of, well, you know what was NATO about? What was the West about? The West has always existed as a civilizational entity. It’s always existed in cultural terms. But in political strategic terms, the West really only came together as a meaningful concept in response to a threatening East, the Communist world, particularly the Soviet Union.

When that went away, the West as a strategic idea did lose a lot of its sense. And you could feel that late NATO flailing around, trying to figure out where to what to do. This has revived the core purpose of the West as a strategic concept. And I think you see it most importantly in this transformation of Germany.

The Germans, for obvious historical reasons, have been very reluctant to have a significant defense posture and even to speak about defense issues and things like that in a larger sense. Merkel was, for example, the most remarkable figure in this regard. She was clearly the most powerful figure in Europe. But she was very hesitant to put herself out there as the leader of Europe, the leader of the world.

When Time magazine chose her as their person of the year, she not only refused to give them an interview. She wouldn’t even sit for a photograph. And I remember asking — I think it was Nancy Gibbs, the editor of Time at the time — what was the last person who refused to give you a sit-down for a portrait when they were named person of the year? And she said, well, it was 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini.

So the Germans were very reluctant to be seen as these big actors on the world stage. And that’s changed. I think one of the things that cripples that united European front is that Britain is no longer part of the European Union. But otherwise, I do think the West has come together. And the United States has become — there’s kind of a de facto U.S. leadership that is much less contested than it was. Macron made waves when he talked about where Europe should go on China. But right now, the pressing issue is Russia. And on that, the Europeans are entirely united and happy to have the United States lead the alliance.

We’ll talk about the U.S. and Ukraine, because you’re having more internal division over U.S. support for Ukraine now. Ron DeSantis called it a, quote, “territorial dispute,” which is a kind of language that is a very clear signaling about his take there. There is a recent economist YouGov poll that found a plurality of Republicans now oppose funding Ukraine. What do you make of the Republican Party’s division and it sometimes feels like mounting turn against U.S. support for Ukraine?

I’m very worried about it. And I think that if you were to look at it in historical terms, what is happening is the Republican Party is returning to its more traditional position on foreign policy, which has been isolation. The Republican Party was the party of isolationism in the ‘20s and the ‘30s. And this was the most bitter debate that took place in America in the last hundred years on foreign policy was not Vietnam. It was entry into World War II. And the Republicans were staunchly on the side of isolationism then.

So that’s just 60 or 70 years ago. The Republican Party is returning to those roots. Trump, as often, in this case, is the kind of weird, intuitive guy who figured out where the base was. DeSantis is trying to follow it. If you look at the people who still support an internationalist foreign policy, my fear is many of them are kind of holdovers from a different world — the Lindsey Grahams of the world.

But if you look at the young hotheads, where the energy and action of the party is, unfortunately, it looks like a very isolationist party. And I think that over time — we’ll see how Ukraine works out, because commitments have already been made, and that Mitch McConnell matters a lot, and people like that matter a lot. But over time, the Republican Party is becoming the party of isolation, which means that having the United States fully engaged in the world, which I believe is profoundly important for the United States and for the world, is going to become a very partisan issue in a way that it has not been since 1942.

How is China’s attitude towards, and role in, the war in Ukraine changed?

It’s very difficult to tell to be honest. People who claim to be able to read what is going on in the minds of five people in Beijing and really one are, I think, exaggerating. But it does appear that they started out with a much more comfortable sense that Russia was an ally. They were going to support Russia. Russia was a big power. It would be able to do whatever it wanted.

The Chinese have a very realpolitik conception of international affairs. There was this one moment where Chinese ambassador had an ASEAN meeting, I think it was, let slip something that you’re not supposed to say. But at one point, when he was being — there was pushback on something the Chinese wanted, he said, look, strong countries, big countries are meant to tell little countries what to do. That’s the way the world works. And then he apologized for it and took it back.

But I think that’s a very revealing statement. The way the Chinese view it, Russia is a big, strong country. There’s this little country on its border, Ukraine. Of course, Ukraine has to be subservient to Russia. And that’s the natural order of things. And that will be established.

I think they’ve come to realize that they underestimated the degree to which the Ukrainians would oppose. They underestimated the degree to which the West would effectively unite and oppose the war. And so what you notice is that they are — first of all, they were not as many profuse statements of love and affiliation. Xi Jinping does not seem to be a very effusive and emotional man, but he has often referred to Putin as something like my dear friend, my very best friend or versions — variations of that.

And they talk about staying up all night talking when they’re together, it’s very —

Exactly. It’s very bro-like.

Yes.

And from two people who do not seem — particularly, Xi, who seems this very formal, measured guy.

Just imagine them in their jammies.

[LAUGHS] And by the way, I think that’s some key to understanding the alliance is a personal one. It’s not just strategy, because the Russians and Chinese have often had difficulties. But these two people are united in two important things. They believe that when regimes lose faith in themselves, as Gorbachev lost faith in the Communist regime, that that is the moment when you crack and crumble. And the second is that the U.S.-led global order must be diminished, eroded, attacked. And so that keeps them very strongly together.

But the Chinese are saying less of that kind of stuff. There are these overtures to Ukraine, which I think are mostly P.R. But the fact that they felt like they had to do some P.R. tells you that they feel like plan A was not working. So I think just as Russia went to a plan B after not being able to conquer Kyiv, I think the Chinese are on a plan B. And the plan B Now is to try to appear to the real audience, which is the global South, that they are not quite in the same category as Russia. They are the neutral power. They keep making the point that they are actually neutral on this war.

I want to put a pin on that point that the real audience there is a global South, because I want to talk at some point about the nonaligned nations here. But this was a way in which Xi’s meeting with Zelensky struck me at least as important, that the fear that people have had for a long time is that China would become to Russia what America and Europe are to Ukraine.

And China boasting a little bit on the world stage, that they’re now talking to both parties, seem to make them twisting into a much more pro-Russian stance a lot less likely, that in terms of how they want to be seen. They want to be seen as a broker, not as the weaponry supplier for Putin.

I think it’s a slight shift. They are still pretty committed to the Russians. The man they sent as the negotiator between Russia and Ukraine was the former Chinese ambassador to Russia, who was well-known to be a deeply pro-Russian diplomat. They’ve never even simply acknowledged that what Russia has done has been to violate Ukraine’s sovereignty in a completely illegitimate manner, which is kind of so strikes me as rule number one in all of this.

But I think you’re right; it’s an important shift. And part of it is about this issue of trying to come across to the Brazils, the South Africas, the Indonesias of the world, as less culpable as the Russians are.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

My read is that tensions between U.S. and China are substantially higher than they were a year ago. That they’re even higher now than they were under Trump, where the rhetoric was high, but there’s always a feeling that it wasn’t being taken quite that seriously. But that now, something has actually shifted in the firmament. And there’s a much deeper sense on both sides that we are in a conflict, even if the boundaries of that conflict are not well-defined. Is that how you read it?

Yeah. I think that’s exactly right. And I think it’s for two reasons. One, the Chinese had made a bet that Trump was an aberration, that he represented, as with so many things, a kind of strange personalistic, populist moment. And that when Biden came into power, you have a kind of return to essentially the Obama-Bush policy, which was broadly consistent.

I mean, U.S. policy toward China was remarkably bipartisan from 1972 all the way up, really, to Trump. It had been fairly consistent. But it turned out not to be true that Biden represented a version of the Trump policy better executed in many ways and more effective. And particularly, the technology bans have really come to bite.

So the second part is that this stuff is exacting a price. I think that the Biden people have made several crucial decisions that are correct, particularly on the technology front. But they have also needlessly provoked the Chinese in ways that, I think, are largely an expression of the domestic politics of the moment.

So take for example, today’s news, the Chinese refused to meet at the highest level on a military to military basis, chairman of the — I think the Secretary of Defense with their equivalent. And the Americans seem chagrined about it. Now, the Chinese guy who they were trying to meet with is under sanctions from the United States — personally under sanctions from the United States. What did they expect? You couldn’t get a third world country to agree on those terms. And they’re asking China, which thinks of itself as, in some ways, a peer of the United States. So there’s that disconnect that is still, I think, unfortunately, part of the U.S.-China relationship, as I say, needlessly, making things more dangerous.

But some of the core policies, particularly around technology or on building alliances with Asia, the Biden people have done the right thing. They’ve done it very effectively. And that’s what’s, I think, unnerved the Chinese.

One of Speaker McCarthy’s early moves when he took the gavel was to create this House Select Committee on China. And it was one of the things he did that Democrats loved and Democrats wanted to be on the committee. And you watched the first hearing of that. Tell me how you understood the tone, the message, what was different between the Democrats and Republicans and what wasn’t. How would you describe that hearing?

Overall, what it made me realize is we all spend our time talking about how terrible it is that there is no bipartisanship in Washington. And I watched it and thought, oh, my God, this is what happens when you have bipartisanship in Washington. You have unthinking groupthink. You have a kind of herd mentality. And that’s what really was going on with this. It became a competition of who could bash China more. It became largely devoted to a kind of existential argument about really why the Chinese Communist Party should be overthrown. That was the subtext of the entire hearing.

And what I worry about it is when we get into those kind of moments in American history, where, first of all, we think the enemy is 10 feet tall, we think we are existentially threatened, we do very bad things. I mean, think of the period in the ‘50s when we thought this about the Soviet Union and McCarthyism and the paranoia about the missile gap and all those kind of impulses that led us into Vietnam, that led the C.I.A. to try to overthrow dozens of regimes around the world, mostly unsuccessfully, but with huge lasting impact in terms of how those countries perceive the United States. One of the most tragic failures of American foreign policy — because all those countries thought of America as very different from the Europeans as being anti-colonial. And very quickly by the late 1960s, the United States was actually in many ways worse, because we had been intervening so much in these places.

Think about after 9/11, the run-up to the Iraq War, the war itself. We lose the capacity to think. We lose the capacity to assess. And so one of the things that I’ve been trying to articulate is the idea we need to rightsize the Chinese threat. The United States is still way more powerful than China. We are the dominant power in the international system. It’s a very complicated international system, because we can’t exercise influence like we used to be able to for all kinds of reasons we can get into.

But China is just not this overwhelming threat to us. If we can rightsize it, if we can act with a certain degree of confidence and calm, and surety we can put together a building blocks that deter China, give it the opportunity if it wants to integrate into the world, preserve our interests. We need to run fast. We don’t need to run scared.

It felt to me a couple of months ago that there was a sense in the Biden administration they’d gone a little bit too far. And so Blinken was going to go to China.

And then this balloon, this Chinese balloon floats across the U.S.

And it’s clear at the beginning the Biden administration doesn’t think this is a very big deal. And then the chorus of pressure from Republicans starts up. And every news network is following the balloon on live balloon cam.

Tell me now with a few months of distance, first, what you think or what the people you talk to think happened with that balloon. What was it? And why did it end up floating in this very obvious public way across U.S. territory? And then what do you think the consequences of that episode have been?

The best I can put together is it was some kind of a — let’s put it this way, a dual-use balloon. It was a meteorological balloon that also had some espionage capacity. It did seem to veer off course.

I think it is one of several balloons that has been sent around various places around the world. And the Biden administration didn’t think it was as big a deal, because, look, the Chinese have hundreds of spy satellites up in the air that are orbiting the Earth 24/7, have taken hundreds of thousands of photographs of every sensitive sites in the United States.

They’re in a lot of our computers.

They’re in a lot of our computers. There is some marginal information you can get from a low-flying balloon, but from everything I can gather, not that much. And of course, it’s important to always remember, we do this much more than they do it. So we’ve got all this capacity. And so nations spy on each other. And so they were trying to keep it, as you say, they were not as perturbed about it.

And then the drumbeat begins. And then it turns it. And maybe this is a wonderful example of modern politics, where, because it’s visual, because you can see it, because CNN can track it —

It was so bad that it was so visual. It was like a low-speed car chase. It was like the O.J. Simpson chase of espionage problems.

Exactly. And every minute it’s up there, people are like, why is he not doing something? And so almost to compensate for that, the Americans shoot down three other balloons, which as far as we can tell, what, $20 weather balloons and some meteorological club had put up in the air. I don’t think they got any compensation from the U.S. government. And by the way, we used — I believe there were $300,000 sidewinder missiles to hit these $20 balloons.

And if you recall, we were going to be shown all the espionage capacities of the Chinese with the first one that was taken down. I’m still waiting. And from what I’m told, there’s not a lot to show, that, yes, it was probably dual-use. But I thought we were going to be shown something that made it absolutely clear what the Chinese were doing. None of that happened.

So in the aftermath of that, the U.S. cancels Blinken’s trip. To my knowledge, it has not been reset. As you said, we were having trouble having the kinds of high-level meetings we would like to have with the Chinese despite other escalatory positions on both sides. It seemed to me, and other people who know more about this have said to me, that the balloon just came at a terrible time. That there was a moment of attempted thaw. And there have been some things after that, a speech by Janet Yellen and others.

But that to the extent, there was this moment of trying to retract the relationship. The balloon was this escalation on both ends. It hardened the politics on both sides. And it has just made whatever was being attempted there a lot harder. Do you think that’s right that there was a real consequence to that? Or did that in the scheme of things not really matter?

What it revealed was that the relationship was very fragile. And that a small thing could take it off course. I think that there would have been another balloon. In other words, something like this would have come up. If the relationship was as fragile as it seems to be, something or the other would have derailed it.

We crashed a spy plane in China in 2001.

The E.P. — whatever it was called — incident with the plane crash in Hainan Island, I think it took 11 days to resolve. Colin Powell was Secretary of State, and he issued an apology. It was famously translated into different ways, where you could translate it to mean regret, you could translate it to mean apology. It’s inconceivable today that we would be able to resolve something like that. It’s inconceivable that Blinken could get away with issuing an apology or regret to the Chinese. So that’s what worries me about where we are with U.S.-China relations.

Look, we are going to be competitive. We’re going to be competitive in the economic realm. We’re going to be competitive in the geopolitical realm. But we want to find a way to have a working relationship with the country that is the second most powerful country in the world, which is, by the way, our third largest trading partner. We trade $700 billion of goods with China every year.

We want to have a good working relationship, so that when moments like this happen, there is a mechanism to resolve them. There is a path to resolve them. There’s channels of communication open. So that things don’t happen that are accidental. Things don’t happen that push you into a corner where you can’t get out. And that’s my fear on both sides. There is so much nationalism now built up that it’s difficult to imagine how you can, quote unquote, “make a concession to China.” That’s why Biden has not removed the tariffs on China.

The Chinese have politics, too. And there’s a reality to how much they can also do, even though it’s a dictatorship. The dictators stay in power partly by judging how far they can move things. So that places us in a very bad situation if, as you say, something like that spy plane incident were to happen again.

So another issue that’s pretty live right now in terms of our relationship with China is TikTok. And I have really strong opinions on this one but rather put my own spin on the ball. The governor of Montana is trying to ban TikTok outright, and not because social media is bad, but because, in his view, China is bad. And TikTok could be a tool of espionage, of influence, particularly, of other kinds of problems. What do you think of banning TikTok?

So as a father of two sort of teenage girls, I delighted the prospect of TikTok being banned, because I have no doubt in my mind that TikTok is harmful. Not TikTok particularly, but social media in general is harmful for teenagers. I believe all that research that I have now studied with some degree of seriousness, that Jonathan Haidt and others have put out. And TikTok is particularly bad because it’s particularly good. By which, I mean it’s particularly effective, in fact, stunningly effective.

But I am very troubled by the argument that it should be banned in general, and that it should be banned because it’s Chinese, because it fundamentally gives up on the idea of the United States as a free society. Let’s say that the Chinese are using TikTok to subtly pass information to us that is anti-American. Do we not want to live in a country where the Chinese government can publish pamphlets that tell us your system of government sucks, ours is much better? We’ve been getting that kind of information since the founding of the Republic.

The idea that we should ban information that is being produced by whomever and whatever form that tells you that America is a bad place, that other countries are better, that our system is right, it strikes me as giving up on the idea of America. So that’s the argument that TikTok is sort of subtly spreading Chinese propaganda. Fine, let them. I mean, we have to be a strong enough country to withstand it.

Secondly, that they’re eavesdropping. This is one of those arguments that the more you push, the more you try to kind of understand what it means, it sort of falls apart. All these companies, social media companies collect data. They all sell them to third parties. The Chinese government would not need to create a company then have the luck of it being super successful, and then use that company to extract data. You could just buy it from Facebook. You could buy it from Google. You could buy it from Amazon. For all we know, they are doing that.

And by the way, as you say, there is a very extensive Chinese cyberspying operation already underway. What they would gain from using TikTok to determine what dance videos teenage girls like? I don’t want to trivialize it, but my point is whatever real information they could gain about people’s preferences, their voting behavior, they can get all that anyway.

– Well let me take the other side of it, particularly on the attentional issue. So we don’t tend to let governments we have a hostile antagonistic relationship with control critical infrastructure, different kinds. We wouldn’t let a country we were not in good relationship with hold a bunch of electrical utilities. We wouldn’t let them run nuclear security. We didn’t like the Soviet Union own television stations here.

To me, part of the argument that makes me friendlier to banning TikTok is that this is attentional infrastructure. And attention is critical. I take your point on the pamphlet. And I would have no problem with the Chinese government placing op eds, running its own newspaper, on some level, publishing a book that was available at bookstores, or you could buy on Amazon. But because we don’t understand how the TikTok algorithm works, we don’t know what people are seeing.

And I don’t think it’s as easy or as narrow in a way as what you would get on there is propaganda meant to make the Chinese government look better. To your point about how Putin understands meddling in other countries to be valuable to him, he’s not meddling in a way to make us like Russia. He’s meddling in a way to take moments of chaos and division and try to make them profound and deep enough to weaken America. So you imagine something like a more contested version of the 2020 election.

Think the 2000 election and the 2020 era, when we have much more polarized parties. And now, on TikTok somebody turns up the dial on just rampant conspiracy theorizing and things that get Americans ever more at each other’s throats. And we don’t even really know that it’s happening. It’s just a kind of attentional dark matter that is making us hate each other more or is making Americans turn towards Trump again or whatever it might be.

The thing that worries me about it is because we can’t track what is happening on it, it could be used for much more sophisticated kinds of attentional manipulation than simply the Chinese government has dropped a bunch of flyers and say, from the Chinese government, China is great.

I think that the problem with that argument is it feels like we are in this digital world, where we can’t track any of this stuff anymore, just that’s the nature of it. And that’s even before you get to A.I. It’s just too diverse. It’s too disaggregated. It’s — the fundamental shift that’s taking place in information is that you were going from a one-to-many broadcasting system to a many-to-many network system.

And when you have a many-to-many network system, there is no central node. It’s all happening at a disaggregated distributed level where the algorithm is noticing what you like and giving you more of that, and noticing what I like and giving me more of that. So it’s very difficult to imagine how you would control any such digital products. So if you have a problem with TikTok in that sense, what comes next? Do we ban Chinese cars, because Chinese cars after our cars are essentially now digital products. They are software on wheels. And the cars know where you go. And maybe there could be listening in on you.

So there is that sci-fi prospect that you can raise about almost anything. And so are we then talking about a complete decoupling of the U.S. and Chinese economies? And are we just comfortable with doing or just with China? Are there other countries wouldn’t want to involve?

And I do come back to the fundamental question, which is, are we not comfortable with information from whatever source in whatever form that criticizes us, that enrages us, that does whatever it does that information is always done?

It feels to me like the distinction you’re making between books and pamphlets on the one side and TikTok on the other is you’re saying, they can do this stuff as long as I don’t think it’s very efficient. If it’s very effective, I’m against it. But if it’s ineffective and inefficient by using books and pamphlets, it’s OK.

I kind of think that is a distinction that I’m making. [LAUGHS]

That’s not a very philosophical distinction. How do you — So you can imagine people saying like, we’re going to allow China to do whatever we want until it gets very good at it. And then — and by the way, this is exactly what the Chinese think. The Chinese think that the United States was perfectly happy to have China integrated into the world economy until they started creating companies like Huawei, which were super good and actually had better 5G technology than we did. And then we suddenly said, oh, by the way, none of the old rules apply.

But I think there is an argument for this. And in a way, weirdly, China doesn’t just think it about us, but they think it for themselves. One thing that is interesting about the TikTok example is it isn’t like China lets Facebook operate in the country. It isn’t like you can have unfettered access to Twitter or LinkedIn or really any kind of major American media or digital media, a Google search. So they’ve developed their functionally almost own internet with its own mediating players. And there are moments of overlap. But it doesn’t look using the internet in China like using it in America.

And precisely, because they think that would be dangerous for them. And I don’t think you have to be out and out an authoritarian government to think that there are dangers with having the attentional structure of your society controlled by companies that can easily be influenced, heavily influenced, by the government you’re in a very antagonistic relationship with.

Well, but think about what you’re saying. You are looking admiringly and longingly at the Chinese Communist Party’s totalitarian control of information and saying, gee, I wish we could have more of that in the United States.

No. But I’m saying I think they might have or of a point, I think the idea that China can’t be right about anything.

But it feels to me like this is pretty fundamental, this question of whether you believe in free flows of information. Look, I think the 15 percent to 20 percent that you’re describing is actually very well taken care of by the Europeans. The Europeans have much stronger regulation on the internet than we do, particularly on social media. And what they’ve been trying to do is, first of all, all the data has to be housed in country, all the data has to be monitored. Google operates under those constraints in Europe, for example.

I think that the kind of compromise that ironically the Trump administration was trying to reach with TikTok made a lot of sense. Yes, of course, the information should all be housed in the U.S. It should all be monitored. It should not be possible for there to be some kind of secret manipulation of it. Technologists who I’ve talked to say that that is essentially what the European regulations achieve. And you could achieve something quite similar.

But I just feel very reluctant to give up on the idea of freedom in this very core space. I don’t want the response of the United States to China’s creation of its own hermetically sealed internet to be that we create a hermetically sealed internet. I have always had the view that the United States has succeeded in part because we air our dirty laundry in public. We allow ourselves to see everything and deal with all the messy dysfunctional realities that that produces. And out of that comes an ability to move forward much better than societies that don’t talk about these problems that in some way repress, suppress them. It sometimes feels like a sewer. But what you’re seeing is real. It’s there. You can’t pretend it doesn’t exist.

So now, let me flip this, because I’ve been taking the hawk position for a bit. I’ve in many ways felt much more comfortable with the idea that the U.S. should have curbs on the level of Chinese technological penetration of the U.S. than that the U.S. should curb China’s technological advancement itself. When I think of, not just provocation, but the level of enmity suggested by a decision to say, hey, we’re not going to have TikTok here, rightly or wrongly. That’s one level. To say, we are going to try to hold you back from the technological frontiers of, say, semiconductors, which is what we have said now.

Even if that is a good move — and I think you suggested earlier you support it, and I have very mixed feelings, and I’m not saying I don’t support it — that has struck me as a genuine phase shift of the relationship and as something where when you imagine how China is looking at us and how they will treat us and understand our relationship to their rise that it really does make good on, I think, every fear they have had, that we are going to try to stop them from becoming the preeminent or even a preeminent world superpower. And to say we’re going to try to hold you back is very different than saying we’re going to try to protect ourselves.

So I actually think that this one is entirely justified, because this is a case where what the United States is concerned about is that the Chinese military, which is, at the end of the day, a competitive military particularly in the South China Seas and around Taiwan, a competitive adversary, is going to acquire technologies that allow it to prevail to enhance its military capacity. And we have always been very sensitive about the idea of militaries that we were not comfortable with acquiring super-advanced capabilities.

There are still in place today sanctions that do not allow the United States to transfer certain technologies to India, because India was not a signatory to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, partly as a result of Cold War stuff, where the U.S. was pro-Pakistan and anti-India. So it’s not such a leap to say that you don’t want China to have this most advanced capacity.

And I think what the administration has done has been to try to use a surgeon’s scalpel to really take the high end of it and cordon that off. Remember, the semiconductor chips that are being denied to China, I think, constitute less than 5 percent of the market. They may actually be even less than 3 percent of the market. So 95 percent, 98 percent of the market is open. It’s where — we buy a lot of Chinese chips. The stuff that goes into washing machines and all that is much of it is Chinese, much of the assembly of computers is.

But what we are saying is that the very high-end, the stuff that really could make a decisive difference on the battlefield, we’re not comfortable with you having it. It is true that the ancillary effect is that it also does slow down Chinese growth.

Yeah. It isn’t just battlefield. I mean, these are the chips that power A.I. They’re the chips that power cloud computing. I mean, they’re not just dual-use in the way that the weather balloon, the Chinese balloon is dual-use. I mean, they really are used for non-military.

But also military.

But also in military, yes.

So the way I would put it is the goal is military. The side effect is — and by the way, they will still be able to do a lot of this stuff, I mean, because you can put chips together. If you don’t have a 5-nanometer chip, you can put 2/10 together. And you’re using more computing power. You’re using more energy. It’s a much more inefficient process. So it’s slowing them down. It’s not killing the Chinese industry as far as I can tell. But I think that’s entirely justifiable.

The one that was more difficult for me, honestly, was Huawei. The thing, I think, we didn’t realize that the degree to which trying to ban Huawei became for them a sign that we were trying to keep them down. Because Huawei was, in many ways, one of the great institutions, a great pride in China. It was a private company that had made it on its own, was outcompeting every Western company at the very high-end technology. I’m not saying we shouldn’t have done it. I’m just saying that for the Chinese, that became a sign of exactly what you’re saying, that this is not a case where the West wants to compete with us. They want to cripple us, so that we can’t grow.

When we talked last time, you said that a major strategic objective for America should be trying to split China and Russia. In the years since, have we been even trying to do that in your view?

No. And I still think it’s a mistake. I think that could much more easily isolate Russia by trying to improve communications with China. But we do it in this way, as I say, with one arm tied behind the back, where we say we’d like to meet with your top defense official — oh, by the way, he’s under sanctions. And how can you have a serious working relationship with the country under those conditions?

That’s where I feel like we have lost the space to maneuver. I mean, this is part of a broader issue, which is, I think, we don’t think a lot about how the world looks like to other countries, how the Chinese would take a response like that. This is one of the reasons why we’re constantly surprised by the Indians. Take for example something like global warming. We keep saying what the Chinese are not doing anything on global warming, because they are horrible anti-American dictators.

Well, the Indians, who are the pro-American democrats, their position on global warming is essentially the same. It’s as hard to get them to do anything. And in fact, the Indians are very ornery on all kinds of things. And part of that is that we don’t understand what the world looks like from New Delhi or from South Africa.

And one of the things we’ve lost in the last 20 or 30 years because of American dominance is we used to a lot about foreign countries. If you look at the people who made their way up the American foreign policy hierarchy, a lot of them were deeply schooled in languages and cultures of other countries.

George Kennan being the perfect example — spoke fluent Russian, had spent years in Russia, understood the society. You’d be hard pressed to find a lot of people like that in America today.

Mike Gallagher, the guy who runs the China committee, you mentioned, in the House — I believe I have this accurately — has never been to China. If you were to ask yourself the people who are making policy toward China in the United States right now, how many of them speak Mandarin? You’d be surprised at how few people know these countries. And that creates a kind of structural tenure for American diplomacy.

And then we’re surprised that — one of my favorite examples is Turkey. This is going back to the Iraq War. We thought of Turkey as this compliant American ally that basically depended on the U.S. for its military assistance. We had lost sight that Turkey had become this consolidated more democratic, more successful, more proud country. And this is almost literally true. We forgot to ask it whether we could use Turkey as a base to invade Iraq. Most people forget Iraq was meant to be invaded on a two-front invasion, from the South and Kuwait up and then from the north through Turkey down.

The Turks surprised the U.S. and said, no, we are now a functioning democracy. This has to go to parliament. And I think it lost in parliament by a couple of votes. So that’s a perfect example of how we haven’t noticed, what I call in the post-American world, the Rise of the Rest. It’s this fundamental change that’s taken place in the international system, where these countries are no longer willing to be pawns on the table. They want to be players in their own right. And we say the right thing sometimes, we mouth the clichés, but we don’t really understand these places.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

There was a great issue of Foreign Affairs that just came out, and I really recommend people go buy it or read it online. Because it was all about the view of America, of the West, from what it called the nonaligned nations, right? So depending how you want to count, and depending on which vote nations representing two thirds of the global population, they’ve not been with us in Russia. They are not necessarily with Russia either.

But they have not bought into the Western narrative that what Russia has done is an unforgivable breach of the system, the sanctions are a good idea, et cetera. And one of the really interesting essays in that issue was a piece by Nirupama Rao, who is a former foreign secretary of India.

And there’s been all this frustration in America that India has been nonaligned around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And she says India’s, quote — and I want to read this for a minute here — “refusal to speak up in Kyiv’s favor has brought it under intense scrutiny and questioning by friends and partners in the West. But India rightfully sees these critiques as hypocritical.

The West routinely cuts deals with violent autocracies to advance its own interests. The United States is improving ties with Venezuela to get more oil. Europe is signing energy contracts with repressive Arab Gulf regimes. Remarkably, the West nonetheless claims that its foreign policy is guided by human rights and democracy. India at least lays no claim to being the conscience keeper of the world.”

And so to your point about how the rest of the world sees us — something that comes up again and again in these essays, and particularly in India’s view — is that we talk about a rules-based order, we talk about a values-based foreign policy, but we only follow that, really, when it benefits us. And so the requests of other countries should go against their own interests — maybe in this case, cheap Russian energy — to back that order rings a little bit hollow.

Yeah. And you’ve pointed to, I think, a very profound problem that we face. One of the central challenges of American foreign policy, for the next 20 to 30 years at least, is how do you sustain the Western-led rules-based international order in the absence of the kind of American dominance that the United States has had? As American dominance fades, what happens to this edifice that we’ve built, that I still believe has been profoundly better than any alternative international system that we’ve — the very fact that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has galvanized so much of the world — not all of it — is that it’s rare.

I mean, since 1945 — there’s a wonderful book by two Yale Law professors which points this out — the number of forcible annexations is down to a handful of times in 75 years. If you go and look at the 75 years before 1945, I mean, it happened so routinely that you could barely count how many times that had happened. So this order is a better order than anything we’ve seen before.

But we don’t seem to realize exactly what you say, which is the hypocrisy that attends the idea that we can constantly deviate from it. We get to invade Iraq. We get to not sign on to the International Criminal Court.

We do things like — we are accusing China in the South China Seas of violating the law of the Seas Treaty, a treaty to which we are not a signatory. And so there’s so much of that kind of inbuilt hypocrisy that we have gotten so used to, that we don’t even bother about it.

Bob Kagan, the writer, once tried to rationalize it by saying, it’s like we are the gardener that is maintaining the Garden of Eden. But to maintain that beautiful garden, that wonderful, peaceful space, the gardener can’t follow the rules. The gardener has to be the thug who enforces the — well, I mean, that’s a very self-serving way of looking at it.

The way that most countries look at it is, when you want oil, you go to Saudi Arabia, and you don’t worry about the fact that it’s a medieval absolute monarchy. When you want to change your policy, as you say, on Venezuela, you suddenly decide, oh, we were trying to overthrow you last year. This year, we want to buy your oil.

And we do this all the time.

And then, when the Indians do it, we shriek, and we say, how dare you? You’re supposed to be a democracy — or South Africa or Indonesia — rather than recognizing that they all have their interests.

I mean, the Indian case is particularly complicated, because the Indians buy most of the advanced weaponry from Russia. Now, why do they buy most of their advanced weaponry from Russia? Largely because the United States wouldn’t sell it to them. During the Cold War, the U.S. was allied with Pakistan. The Indians also violated the N.P.T., which, by the way, so did the Pakistanis.

Nuclear —

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, by testing nuclear weapons. And so the Indians have developed this dependency. But there’s a larger issue also, which is, the Indians have always relied on Russia for unwavering support on something like Kashmir, which is the disputed territory between India and Pakistan.

And they know that the Russians will be the reliable veto in the U.N. Security Council on that. So they’re not going to burn their bridges with the Russians all at once. They’ve distanced themselves a little bit. They’ve done some things.

A better way to put it would be this. America has never understood nationalism. You know, one of our biggest problems is that we look at the world and we say to ourselves, but we’re bringing you all these wonderful things. Why don’t you just take them and let us shower you with these benefits and tell you what to do?

And we don’t understand how strong that desire of doing your own thing is, whether it’s in Iraq, whether it’s in Vietnam, whether it’s in Cuba. We don’t understand how the resistance to external domination can be so powerful.

There’s this very famous, perhaps apocryphal, story — when Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, says in frustration to Gandhi when they are negotiating independence. We can’t just leave India. If we leave India, it will be chaos. And Gandhi looks at him and says, yes, but it will be our chaos. And that sense that something imperfect that is ours is better than something even better that might be provided by a foreign domination.

But this is something you would understand better about the sociology of the American foreign policy establishment. I’ve tended in my career to cover domestic policy. I can tell you a lot about the weird psychology of American domestic policy fighting, but I’ve been doing particularly more reporting over the past year or two on America and China.

And I’m constantly told, when I ask, well, why don’t we want this? What gives us the moral standing to say China should not become powerful in this way, or we should not permit this, or — and I’ll hear, well, China doesn’t really support the rules-based international order. We’re trying to protect the rules-based international order.

And then, I’ll say, OK, but Iraq, and OK, but these treaties. And I mean, nobody thinks, globally, that we follow that order. And I would say that the consistent response I get from people who genuinely, I think, believe with all their heart in that order, and also supported a number of deviations from it, describe it as, yeah, well, nevertheless.

And I genuinely am puzzled by it. Because every contact I have ever had with foreign policy representatives from other nations — our deviations loom very large in their minds. I do believe there is a belief among American — at least liberal foreign policy establishment — that the rules-based international order is the great achievement in foreign policy of America.

And yet, the damage of deviation after deviation — it really goes unremarked. And it continues — I mean, many in Europe think, I think, fairly correctly, that we are, at this point, operating with Buy American provisions and trade provisions that are beginning to look a lot like World Trade Organization violations, so that for everything we talk about free trade, the direction of industrial policy in America, which I support in a lot of ways, but it undermines a lot of what we’re saying about friend-shoring and about the kind of world we seek to build.

There just seems to me to be a very deeply unresolved tension in the way that we don’t justify our foreign policy based on Pax Americana. We justify it based on a rules-based order that we abide by sometimes and not others. And you know, you read this “Foreign Affairs” issue, but it’s obviously not just there. And the damage those contradictions do to our ability to mobilize other countries to defend this order that we say we’re defending seems much larger than we’re willing to admit or face up to.

Yeah. I mean, you’re highlighting, really, a central, central issue. Because as you put it, we don’t justify our policy on the basis of Pax Americana. We don’t justify saying, we’re the United States, we want to be the dominant power, and we want a world that allows our interests and our power to be protected and enhanced.

We try to articulate a set of ideas that could capture the imagination of the world, and that’s always been the American way ever since Franklin Roosevelt. And you know, those have, to a large extent — in the ‘40s and ‘50s, the whole decolonizing world was looking to America. And people like Ho Chi Minh would make overtures to the Americans.

So there is a power in those American ideas, because we do think in those broader terms. But we then never seem to understand how serious it is that we are violating these ideas, these rules, and we never try to explain it. We never tried to do the diplomacy that was surrounded.

So for example, forget even the naked protectionism of the Biden administration, which I think is clearly a violation of the kind of free-trade order that we’ve created. Take something like the freezing of Russian assets and the use of the dollar in that way.

At one level, I totally support it. But I have been urging Biden to give a speech saying, look, we understand that this seems like a very arbitrary use of power that goes against the rules that countries’ foreign reserves are sacrosanct.

We have only done it in this very unusual circumstance, where a country decided in an unprovoked fashion to invade its neighbor. That is the core violation of the rules-based order. And because of that, in order to fight that fire, we have used a little fire ourselves.

We assure you we would never do something like this on a routine basis. This is a kind of one-off. We don’t try to even articulate it that way, and that’s where some of the arrogance comes in.

We don’t think to ourselves, we need to explain these things. And forget our enemies. When Trump pulled out of the Iran deal, because of the power of the dollar, he kept in place American secondary sanctions.

So even though the rest of the world wanted to trade with Iran, they couldn’t. And that has so frustrated the Europeans —

Because we would sanction them for trading.

Right. It’s a very complicated — but basically, if the Americans say, we will sanction you for trading, even though you’re part of the Iran deal, effectively, they have to be cleared through the New York Fed. This is what I’ve called our last true superpower weapon.

And because of that, the Europeans got so frustrated, because they thought that Trump’s pulling out of the Iran deal was totally unjustified, unilateral, entirely a violation of the rules-based order. They set to work trying to find some alternative to a dollar-based system. You know, we have a system called SWIFT, and the Europeans have been trying to set up a different one.

Now, I know all the economists tell me, it’s not going to work. The dollar is inevitably the currency of last resort. That may all be true, but what does it say when your closest allies are now dead-set on a project that for them may take decades but they believe they will fulfill to wean themselves off the dependency on the dollar because they don’t trust that you will use that weapon in a fair, rules-based manner, that you’re going to use it arbitrarily, capriciously, and for, as you say, America’s narrow, selfish interests.

I feel as though if we’re not careful, we will find that the thing that destroyed America’s dominant position in the world, America’s ability to lead the world, to shape a rules-based international system, was not some great external threat like China. It was us. It was the mistakes, the arrogance, the parochialism, the hubris. All that combined will prove the much more potent weapon that undermined American hegemony than the Chinese or the Russians.

This feels to me like the year that, narratively — and probably in reality, too — India began moving towards superpower status. I think that the estimation that it’s now the most populous nation in the world was a big moment of pivot in how it was seen. It is growing faster, say, than China. It is much younger than China.

Modi is a very complicated and very checkered figure, but he does seem to have been successful in getting things built in India at a really astonishing rate. The digitization of a lot of Indian infrastructure and money and other things is a truly huge accomplishment. You’ve written some pieces about trips you’ve taken recently and the reasons you have optimism there. Give me a bit of your overview of what has shifted in India, such as their role in the world is shifting.

I think that now, with so much hype about India, I sometimes feel like I almost have to tell people when they’re going to go, just brace yourself. It is still a very poor country. You know, India’s per capita GDP is still under $3,000 a year. China’s — just give you a quick — I mean, Chinese economy is five times larger than India’s.

So there are a lot of things that have changed and a lot of positive currents that have taken place, but it’s important to keep that framework in perspective.

I think what has happened in India is there has been a shift away from the old, statist, state-planning, socialist economics that began in the early 1990s, that has been galvanized in a way that only can happen in a democracy where you had alternations of government, so that the opposition initially criticized it, then they came into power, they now have implemented many of the same changes that have been two or three changes of government.

And a certain amount of critical mass has taken place. Many of the things that have been taking place in this government were planned in the previous government, the Congress government. For example, the digital infrastructure, Aadhaar, was actually an innervation of the previous government but has come to fruition under this one.

Could you just briefly explain what Aadhaar is?

So the Indians innovated, in a way that we could all learn something around the world from, in creating a biometric ID system, where basically, 99.9 percent of Indian adults now have a biometric ID. They have a code.

And what they’ve done is created a kind of digital ID that — for example, I think the easiest way to explain this would be, you’re given this number at birth, or if you are an adult, you applied for it, and they were able to get it to everybody. If you want to open a bank account in India, it now takes 90 seconds.

You know, and so you can imagine all kinds of applications where the initial platform is government-owned, open to everyone, and free, which allows you to build all kinds of new digital infrastructure, businesses on it. Everything else that exists on that scale is a private monopoly.

I want to underscore how impressive an achievement that is — to get a digital ID to 99.9 percent of Indian adults in just a few years. So how do you assess Modi as a leader or a manager, having helped shepherd a massive project like that through?

Modi is an extremely competent manager. I don’t think he is the kind of Thatcherite reformer that people were expecting. That’s not his mentality. When I’ve spoken to him, the sense I always get from him is he wants real competence, real accountability, but he doesn’t believe that the big state-owned banks should be privatized. He doesn’t believe — that’s not his ideology.

His ideology is, I want India to be strong, the Indian government to be strong but competent, delivering, executing well. And he’s done that. He’s done that remarkably well. In physical infrastructure, he expanded the digital infrastructure.

And those two things, really — the two infrastructure booms — the digital side, where India is really the world leader. India has the only billion-plus internet platform that is not privately owned. Every other global billion-plus-person internet platform — Google, Facebook — are all private.

And what that means is that the whole Indian private sector builds on that public edifice, which means it’s a much freer, much less monopolistic, much more open, much more efficient system. So they’re a real world leader in that.

And the second is the public infrastructure, where India’s famously been terrible at, but is getting much, much better. And you could see it. For the first time when I went to Mumbai — you know, I’ve been several times, but it kind of caught my attention this time — you look around, and the number of cranes you see reminded me of Shanghai 20 years ago.

You know, you’re suddenly seeing that kind of burst of infrastructure. And all of that is lifting the country up. Now, there is a reality, a dark side to some of this.

Modi is very efficient, and he’s very skillful, even on foreign policy. There is also a Hindu-nationalist agenda that certainly has left Indian Muslims feeling very dispossessed and persecuted — Christians, in some cases, some lower castes, the South, because of a certain — the certain kind of Hindu nationalism that is very Hindi-oriented, Hindi being the dominant language in the North. A simpler way to put it — it’s a very particular nationalist project that leaves a lot of people feeling excluded.

As Modi has consolidated power, has his Hindu nationalism and that of his party gotten worse and more intense or moderated?

More intense, without any question. He’s one of the most effective politicians I’ve ever seen in my lifetime. He is really brilliant in some ways.

The last phase of Hindu nationalism under — there were two previous leaders, Advani and Vajpayee. They came across a problem, which was — it was seen fundamentally as a kind of upper-caste project. And the Indian lower castes, who make up 50 percent of the Indian population, didn’t really buy in. And that, ultimately, is what undermined it.

Modi found a way to resolve that tension, in some ways, by doing very clever alliances with lower-caste parties, in some ways, by reminding the lower caste that at the end of the day, they were all united as Hindus against the Muslims. You know, so there’s a certain bit of what Southern politicians used to do with working-class whites, of saying, you may be poor, but don’t forget, your social status is one step above you-know-who.

So there’s some of that going on.

Part of it is they’ve run — made very digitally savvy, very good at what they do. But they have been able to, as a result, have a freer rein on rewriting of textbooks, rewriting of history, renaming of towns, ignoring or bypassing — I mean, Muslims have been in India for 1,000 years. And if you look at some of the symbols of the new India, the new Indian parliament, you’d be hard-pressed to find many visual instances of that.

There’s an interesting section in Rao’s essay where she talks about how, look, India and China have this very complicated relationship. In fact, there have been periods between them that have left Indian soldiers dead. And they are somehow managing this competition, cooperation, and are very much in competition for what they both seem to see as leader of the Global South.

You talked about that as being one of the key audiences now. And India very much seems to see at least its great foreign policy goal now as being understood to be the leader of the Global South. Is that plausible? And how does that competition relate to the role we want to play there?

I think fundamentally, the Indians don’t really want to be leaders of the Global South. Because India is still, basically, not that interested in the global role. China is. India is, partly because it’s much — in relative terms, much poorer, still moving its way up the developmental ladder. But I’ve always thought that India reminded me of America in the 19th century, which is this big, messy, chaotic democracy that’s largely internally focused.

It’s not that interested in what’s going on in the rest of the world. And to the extent that it is, it’s largely focused on India’s interests and very comfortable with being completely honest about that very narrow preoccupation. If you read the Indian newspapers, what is astonishing to you is, you read these big fat newspapers, full of everything, and they’re still, for the most part, free, even though somewhat intimidated.

There’s almost nothing about the international world. And it’s particularly true if you read newspapers in Hindi or a local language, which is what the vast majority of Indians read. There’s just very little interest in the outside world.

What is our direct relationship there shaping up to be? And noting — to something you were saying earlier about sanctions, before Modi became leader of India, he was under American sanctions. So I get the sense of some internal consternation that we’ve not been able to hold India closer to us during the Ukraine conflict.

But there’s also real fear about what Modi represents in India. So we’ve talked a lot about how American-Chinese relations have dissolved into something worse. Obviously, we’re not there with India, but does that seem like a relationship we are building towards it being closer, or that we are on track for it to become more troubled?

No, I think ultimately, the United States and India will have a closer relationship, a deeper relationship, and one that will be enduring. Because the fundamental bonds that will tie India and the United States together are going to be society-to-society bonds, not state-to-state bonds. India is one of the two or three most pro-American countries in the world.

I think India, Israel, and Poland — usually, in the 70 percent-plus say they like — have a favorable view of America. And it’s palpable if you go to India. Every businessman wants to do business with America. Every kid wants to find some way to get to America for education.

The magnet of America is very powerful. English is an Indian language, even though probably only 10 percent or 15 percent of Indians speak it. But there is still the sense that it’s — India is very comfortable in the world of English, and so they can access America and American culture very easily. And by and large, America still has a very attractive image for India.