Lalaine Basa would buy a kilo of onions to make spring rolls at her catering business north of Manila. She’s now changed her recipe to use half the amount because of soaring prices in the Philippines.

In the Moroccan capital Rabat, Fatima no longer buys onions and tomatoes because they are too expensive. She gets artichokes to cook tagine instead. “The market is on fire,” said the mother of three.

The experiences of the two women more than 12 000 kilometres apart shows how the global crisis over food supplies is taking an alarming twist: threatening to consume ingredients critical to the world’s nutrition.

The costs of wheat and grains have fallen in recent months, easing concern over access to some staples. But a combination of factors is now shaking up the vegetable market, the backbone of a healthy, sustainable diet. And at the sharp end of that is the humble onion.

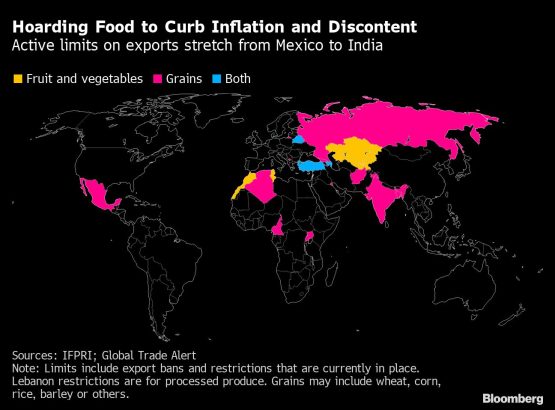

Prices are soaring, fueling inflation and prompting countries to take action to secure supplies. Morocco and Turkey have halted some exports, as has Kazakhstan. The Philippines has ordered an investigation into cartels.

Restrictions have also gone beyond onions to include carrots, tomatoes, potatoes and apples, hampering availability worldwide, the United Nations and the World Bank warned this month. In Europe, empty shelves have forced UK supermarkets to ration purchases of some fruit and vegetables after a weak harvest in southern Spain and North Africa.

“Simply having enough calories is not good enough,” said Cindy Holleman, a senior economist at the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation in Rome. “Diet quality is a critical link between food security and nutrition. Poor diet quality can lead to different forms of malnutrition.”

Onions are the staple of cuisines across the world, the most consumed vegetable after the tomato (technically a fruit). About 106 million metric tons are produced annually — roughly the same as carrots, turnips, chillies, peppers and garlic combined. They’re used in everything from the base flavouring of curries and soups to fried toppings on hotdogs in the US, where futures trading in them has been banned since 1958 after an attempt to corner the market.

The jump in prices is a knock-on effect from disastrous floods in Pakistan, frosts damaging stockpiles in Central Asia and Russia’s war in Ukraine. In North Africa, meanwhile, farmers have battled severe droughts and an increase in the cost of seeds and fertilisers.

Poor weather has hit Moroccan growers particularly hard. At a market in the Ocean district in central Rabat, Fatima said vegetable prices remain “exuberantly high” even with the ban on sending onions and tomatoes to West Africa introduced by the government this month.

Clutching a bag of artichokes, the 51-year-old retired government worker said her earnings no longer last until the end of the month. That financial squeeze will be felt even harder during Ramadan, when Muslims traditionally break their daily fast with a large meal before celebrating the Eid holiday.

“We are eating more lentils, white beans and fava beans and soon we will settle for rice,” said Fatima, who declined to give her full name because of the political sensitivity in Morocco surrounding food inflation.

Vegetable seller Brahim has been working in the Ocean market for over 30 years. Business has been slow, he said.

“I thought only single men bought vegetables by the piece, especially the losers,” said Brahim, 56. “Now, I bow my head when I see people who have been shopping at my stall for 10, 15, 23 years ask me in a broken voice for one tomato, one onion, one potato. People are at their limits.”

In the Philippines, a dearth of onions has compounded shortages of everything from salt to sugar over the last few months. Prices became so absurdly high that they briefly cost more than meat, while flight attendants were caught smuggling them out of the Middle East. The government of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has boosted imports to tame the highest inflation in 14 years.

“I just use the tiniest bits of onions,” said Basa, 58. Her almost three-decades-old business in Bulacan province caters for birthdays and weddings. “I have to adjust because I don’t want to raise prices too much and lose my customers.”

In Kazakhstan, the spike in prices has prompted authorities to tap strategic stockpiles while its trade minister urged people not to buy onions by the sack amid a panic rush to secure supplies in local supermarkets.

That’s on top of an export ban, also introduced in recent weeks by Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan — the world’s top per-capita consumer thanks to onion-heavy national dish qurutob. Elsewhere, Azerbaijan is putting “limit” on sales and Belarus will license shipments.

As the cost of buying nutrient-rich vegetables and fruit soars and incomes struggle to keep up, healthy diets are getting out of reach. More than 3 billion people cannot afford a healthy diet, the most recent UN figures show.

That will rise up the political agenda globally, and nutrition will be a much more prominent part of government thinking, said Tim Benton, research director in emerging risks at Chatham House in London. He calls it a “nutrition time bomb” that’s exploding slowly.

“It’s not just teetering on the edge of famine in the Horn of Africa that should worry us about the current crisis,” he said. “It’s the widespread growth of poor nutrition. Nutrition was already startlingly bad on a global basis, beforehand.”

A worker carries a sack of onions at a wholesale market in New Delhi, India. Image: Anindito Mukherjee/Bloomberg

For now, while many governments will happily subsidise imports of wheat or flour to keep their people happy, there’s limited support for vegetable growers. The result is that the world produces too much starchy grains, sugar and vegetable oils than the nutritional needs, but only about a third of the fruit and vegetables needed, Benton said.

Like bread, onions also have shown the potential to ignite civil unrest. In India, which has banned exports on and off for years, high prices were cited for the Bharatiya Janata Party losing the vote in New Delhi in 1998. Two decades later, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in his campaign to gain reelection, said farmers are his “TOP” priority, meaning the tomato, onion and potato.

“The major grains are really important from a kind of emblematic functioning of global food security and starvation,” said Benton. “But for many countries, it’s these additional things that matter when it comes to keeping the populace happy. This is in a sense the tip of the iceberg.”

© 2023 Bloomberg