At the start of a new year, South African investors are once again asking tough questions about what to do with their hard-earned money.

In contrast to other years, perhaps, there was little of the usual January optimism. Load shedding is taking an economic and psychological toll, never mind all the other problems the country faces.

It is not hard to understand how load shedding disrupts economic activity. Electricity is a key input in any modern economy and most businesses require a reliable supply. The extent of the damage from load shedding will differ from sector to sector and firm to firm, depending on how energy-intensive it is and whether back-up sources are available. It will also depend on how severe load shedding is from day to day.

The most difficult thing to quantify is the investment that does not take place and the jobs that are not created because firms lose confidence in the future.

However, one benefit of 15 years of load shedding is that many businesses are now used to operating in this difficult environment. Unfortunately, the globally elevated diesel price means running a generator is also becoming more and more expensive.

Local businesses therefore face the twin pressures of lost trading hours and higher input costs.

As an example, Shoprite noted late last year in its results that it spends R100 million per month running generators. This number is likely to be on the rise since – as Eskom and the government have admitted – there are no quick fixes.

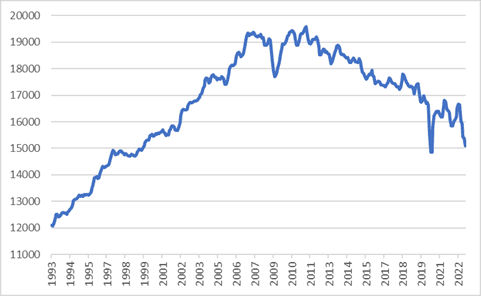

15 years of falling Eskom output

Source: Stats SA

There are therefore three remaining questions:

- After years of empty promises, is there any reason to believe that load shedding can end?

- Does this period of literal darkness signal the widely heralded failure of the state?

- And how should we think about asset allocation when the global environment is not moonshine and roses either?

Lights out

Eskom is clearly in a much worse state than previously thought. It’s only in very rotten organisations where CEOs are assassination targets and the army has to protect key assets.

Apart from being preyed on by criminal syndicates, it is also deeply indebted, owed billions by municipalities, and its fleet of ageing power stations would challenge even the most well-run utility.

It’s also clear that while some in government are enthusiastic about private energy generation, particularly renewables, others aren’t.

This tension has stalled important progress, but now load shedding is so intense, and the 2024 election so close, that change is finally afoot.

In an ideal world, policymakers will change their approach when and where necessary. In the real world, it often takes a sense of crisis for this to happen. The more entrenched the position, in this case the government’s ideological commitment to state ownership and control of key network industries, the bigger the crisis must be.

The good news is that the load shedding crisis is now so big that it can no longer be ignored.

The sense of crisis will also be growing in the minds of business leaders who might have been sitting on the fence regarding securing alternative supplies or ways of running their businesses. Last week, Toyota South Africa said it would spend R800 million to move its plant, warehouses and offices 100% to renewable energy by 2028. More and more companies are announcing plans in this direction.

Also last week the City of Cape Town became the first municipality to offer to purchase electricity from businesses and households, providing a major incentive to install rooftop solar. Other well-run municipalities are likely to follow suit.

Combined with regulatory changes that allow for unlimited generation for own use, we are finally in a position to unleash the power of the private sector. It is an unfortunate reality that South Africa increasingly turns to private provision of public goods – education, health, security and now electricity – widening the gap between the haves from the have-nots. But it is the reality nonetheless, and typical of many emerging markets.

The bad news is that the crisis is not visible enough to the general public in the case of other state-owned entities (SOEs), and therefore decisive action is absent.

Transnet, whose operational inefficiency is matched only by its financial fragility, is a major factor holding the economy back, but is not front of mind for voters. The Richard’s Bay Coal Terminal’s results show that 2022 coal exports fell to levels last seen in 1993 due to the problems at Transnet Freight Rail, despite elevated global coal prices.

Read/listen: Why did South Africa export the least coal in 30 years in 2022?

Roadmap

The National Energy Crisis Committee (Necom, to add another acronym to the full line-up) roadmap has five key elements. The first is to improve supply from Eskom, while the remaining four relate to ways of crowding in private production.

Fixing Eskom is a mammoth task, so it is best to assume only limited progress will be made on this score. The question is then whether private sources of supply can make up the shortfall. They can, but there are two caveats: it will take some time, and progress will be uneven. For instance, load shedding seems likely to end in Cape Town before it does in other metros.

In the meantime, the economy does not collapse, it just treads water.

Billions of rands will go into alternative energy sources, and this should offset some of the negative impacts of load shedding. Falling inflation should also ease pressure on households.

Nonetheless, the South African Reserve Bank (Sarb) in its latest forecast points to real growth of only 0.3% this year and 0.7% next year, with load shedding subtracting an estimated two percentage points per year. It should be noted, however, that the bank is more pessimistic than private sector forecasters.

South African growth and inflation with Sarb forecasts

Source: SA Reserve Bank

Not a failed state

The second question picks up on this theme. Is South Africa becoming a failed state?

One does not have to look far for articles arguing that this is the case, that the country is on a cliff-edge, though wading through a swamp would be the more appropriate metaphor.

The World Economic Forum’s 2023 Global Risk Report indicates that local business executives view ‘state collapse’ as their number one risk.

Leaving aside the fact that state failure is a problematic concept with no fixed definition, the answer must be ‘no’ for the simple reason that people conflate the government and the state.

The two terms are often used interchangeably, but in this context the ‘state’ is broader than the government. The government fails to adequately provide key public goods, and indeed is downright dysfunctional in some areas, especially at municipal level.

But the state of South Africa, the country and the nation, is more than the government of the day. It comprises civil society, opposition parties, businesses, the financial sector, unions, universities, courts, artists, a noisy free press, you and me.

State failure happens when the rest of society cannot be a bulwark against a predatory government, whether because they are too divided (as in Lebanon), too oppressed (Syria) or too poor and traumatised (Haiti).

An inefficient government is also not the same as a malicious or parasitic government. In Zimbabwe or Venezuela, elites at the top were content to let the country collapse as long as they could continue feasting on the carcass. No one was able to stop them.

South Africa has much stronger democratic institutions, imperfect as they are. We must not take them for granted.

The fact that the Sarb could hike interest rates in a tough climate not long before an election speaks to its independence, for instance. This independence is enshrined in the Constitution. Fortunately for beleaguered borrowers, it only raised the repo rate by 0.25% to 7.25%. The smaller increment reflects the weaker growth outlook, but also that the global inflation picture looks better, and the dollar is less menacing.

Investing in the dark

The final question is perhaps the most difficult. The most important element of successful asset allocation is probably that it should be done without emotion. This immediately puts South Africans at a disadvantage since our frustration levels reach boiling point daily.

The simple but extreme solution some advocate is to take all their money abroad. Fair enough, most of us are probably overexposed to local assets if you include your primary residence in your investment portfolio. But this approach has two drawbacks: firstly, you might be missing out on local opportunities and secondly, the rand has a habit of moving about wildly.

South African bonds and equities have historically delivered solid real returns, among the best in the world, despite persistent political uncertainty and boom-bust economic cycles. But this has always required patience.

In particular, domestic interest rates are higher than in developed and most emerging markets, which is in turn is a reflection of the tough environment as higher risk demands higher returns.

As for the rand, it has weakened over time against major currencies and is likely to continue doing so. But it can appreciate for uncomfortably long periods, especially after a blow-out event – as we saw in 2002, 2008, 2015 and 2020. We may be in the middle of another such an episode.

The rand blew out 35% between June 2021 and November 2022 as the dollar surged. But now the dollar is easing, and the rand has been gaining ground despite the load shedding debacle.

When the rand appreciates, it detracts from global returns. This is particularly problematic for investors in offshore fixed income since the currency’s moves can easily be higher than global bond or cash yields.

The rand gained 7% over the past three months, which is more than you can expect to earn from US or UK cash or short-dated bonds in two years.

South African bond and equity yields

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

South African bonds and equities remain cheap, despite a good start to the year, precisely because the market is discounting load shedding and the other problems we are all too familiar with.

To unlock this value does not require that everything suddenly become hunky-dory, simply that reality turns out to be somewhat less bad than feared and the issues have already been priced in. This does happen. The recovery from Covid was stronger than anyone imagined back in the dark days of 2020. If the value does not get unlocked? You can still earn a 3.6% annual dividend yield from the JSE All Share and 11% interest from the long end of the All Bond Index.

All this means is that there is still merit in a diversified approach that includes lots of rand-hedge and global exposure, but also makes full use of local opportunities.

Ultimately, the exact mix will depend on individual circumstances, but time and time again making knee-jerk investment decisions when the emotional temperature runs high has proven counterproductive.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth.