The takedowns in recent times by Twitter and Facebook of greater than 150 bogus personas and media websites created within the United States was disclosed last month by web researchers Graphika and the Stanford Internet Observatory. While the researchers didn’t attribute the sham accounts to the U.S. army, two officers conversant in the matter mentioned that U.S. Central Command is amongst these whose actions are dealing with scrutiny. Like others interviewed for this report, they spoke on the situation of anonymity to debate delicate army operations.

The researchers didn’t specify when the takedowns occurred, however these conversant in the matter mentioned they had been throughout the previous two or three years. Some had been latest, they mentioned, and concerned posts from the summer season that superior anti-Russia narratives citing the Kremlin’s “imperialist” warfare in Ukraine and warning of the battle’s direct influence on Central Asian international locations. Significantly, they discovered that the faux personas — using techniques utilized by international locations comparable to Russia and China — didn’t achieve a lot traction, and that overt accounts truly attracted extra followers.

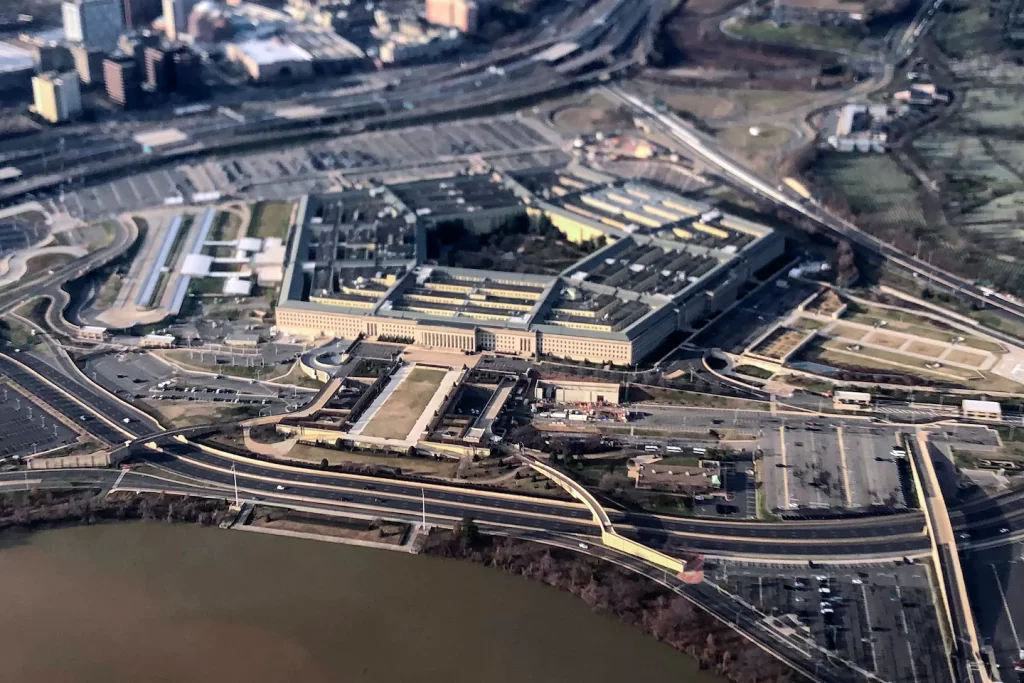

Centcom, headquartered in Tampa, has purview over army operations throughout 21 international locations within the Middle East, North Africa and Central and South Asia. A spokesman declined to remark.

Air Force Brig. Gen. Patrick Ryder, the Pentagon press secretary, mentioned in an announcement that the army’s data operations “support our national security priorities” and should be performed in compliance with related legal guidelines and insurance policies. “We are committed to enforcing those safeguards,” he mentioned.

Spokespersons for Facebook and Twitter declined to remark.

According to the researchers’ report, the accounts taken down included a made-up Persian-language media web site that shared content material reposted from the U.S.-funded Voice of America Farsi and Radio Free Europe. Another, it mentioned, was linked to a Twitter deal with that previously had claimed to function on behalf of Centcom.

One pretend account posted an inflammatory tweet claiming that kinfolk of deceased Afghan refugees had reported our bodies being returned from Iran with lacking organs, in keeping with the report. The tweet linked to a video that was a part of an article posted on a U.S.-military affiliated web site.

Centcom has not commented on whether or not these accounts had been created by its personnel or contractors. If the organ-harvesting tweet is proven to be Centcom’s, one protection official mentioned, it might “absolutely be a violation of doctrine and training practices.”

Independent of the report, The Washington Post has discovered that in 2020 Facebook disabled fictitious personas created by Centcom to counter disinformation unfold by China suggesting the coronavirus chargeable for covid-19 was created at a U.S. Army lab in Fort Detrick, Md., in keeping with officers conversant in the matter. The pseudo profiles — lively in Facebook teams that conversed in Arabic, Farsi and Urdu, the officers mentioned — had been used to amplify truthful data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in regards to the virus’s origination in China.

The U.S. authorities’s use of ersatz social media accounts, although licensed by regulation and coverage, has stirred controversy contained in the Biden administration, with the White House urgent the Pentagon to make clear and justify its insurance policies. The White House, companies such because the State Department and even some officers throughout the Defense Department have been involved that the insurance policies are too broad, permitting leeway for techniques that even when used to unfold truthful data, danger eroding U.S. credibility, a number of U.S. officers mentioned.

“Our adversaries are absolutely operating in the information domain,” mentioned a second senior protection official. “There are some who think we shouldn’t do anything clandestine in that space. Ceding an entire domain to an adversary would be unwise. But we need stronger policy guardrails.”

A spokeswoman for the National Security Council, which is a part of the White House, declined to remark.

Kahl disclosed his assessment at a digital assembly convened by the National Security Council on Tuesday, saying he needs to know what kinds of operations have been carried out, who they’re concentrating on, what instruments are getting used and why army commanders have chosen these techniques, and the way efficient they’ve been, a number of officers mentioned.

The message was basically, “You have to justify to me why you’re doing these types of things,” the primary protection official mentioned.

Pentagon coverage and doctrine discourage the army from peddling falsehoods, however there are not any particular guidelines mandating using truthful data for psychological operations. For occasion, the army generally employs fiction and satire for persuasion functions, however usually the messages are supposed to stay to info, officers mentioned.

In 2020, officers at Facebook and Twitter contacted the Pentagon to boost considerations in regards to the phony accounts they had been having to take away, suspicious they had been related to the army. That summer season, David Agranovich, Facebook’s director for international menace disruption, spoke to Christopher C. Miller, then assistant director for Special Operations/Low Intensity Conflict, which oversees affect operations coverage, warning him that if Facebook may sniff them out, so may U.S. adversaries, a number of individuals conversant in the dialog mentioned.

“His point‚” one particular person mentioned, “was ‘Guys, you got caught. That’s a problem.’ ”

Before Miller may take motion, he was tapped to move a special company — the National Counterterrorism Center. Then the November election occurred and time ran out for the Trump administration to deal with the matter, though Miller did spend the previous couple of weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency serving as appearing protection secretary.

With the rise of Russia and China as strategic rivals, army commanders have needed to battle again, together with on-line. And Congress supported that. Frustrated with perceived authorized obstacles to the Defense Department’s potential to conduct clandestine actions in our on-line world, Congress in late 2019 handed a regulation affirming that the army may conduct operations within the “information environment” to defend the United States and to push again in opposition to international disinformation geared toward undermining its pursuits. The measure, often known as Section 1631, permits the army to hold out clandestine psychologic operations with out crossing what the CIA has claimed as its covert authority, assuaging a few of the friction that had hindered such operations beforehand.

“Combatant commanders got really excited,” recalled the primary protection official. “They were very eager to utilize these new authorities. The defense contractors were equally eager to land lucrative classified contracts to enable clandestine influence operations.”

At the identical time, the official mentioned, army leaders weren’t educated to supervise “technically complex operations conducted by contractors” or coordinate such actions with different stakeholders elsewhere within the U.S. authorities.

Last 12 months, with a brand new administration in place, Facebook’s Agranovich tried once more. This time he took his grievance to President Biden’s deputy nationwide safety adviser for cyber, Anne Neuberger. Agranovich, who had labored on the NSC below Trump, informed Neuberger that Facebook was taking down pretend accounts as a result of they violated the corporate’s phrases of service, in keeping with individuals conversant in the change.

The accounts had been simply detected by Facebook, which since Russia’s marketing campaign to intrude within the 2016 presidential election has enhanced its potential to establish mock personas and websites. In some circumstances, the corporate had eliminated profiles, which seemed to be related to the army, that promoted data deemed by fact-checkers to be false, mentioned an individual conversant in the matter.

Agranovich additionally spoke to officers on the Pentagon. His message was: “We know what DOD is doing. It violates our policies. We will enforce our policies” and so “DOD should knock it off,” mentioned a U.S. official briefed on the matter.

In response to White House considerations, Kahl ordered a assessment of Military Information Support Operations, or MISO, the Pentagon’s moniker for psychological operations. A draft concluded that insurance policies, coaching and oversight all wanted tightening, and that coordination with different companies, such because the State Department and the CIA, wanted strengthening, in keeping with officers.

The assessment additionally discovered that whereas there have been circumstances wherein fictitious data was pushed by the army, they had been the results of insufficient oversight of contractors and personnel coaching — not systemic issues, officers mentioned.

Pentagon management did little with the assessment, two officers mentioned, earlier than Graphika and Stanford printed their report on Aug. 24, which elicited a flurry of stories protection and questions for the army.

The State Department and CIA have been perturbed by the army’s use of clandestine techniques. Officers at State have admonished the Defense Department, “Hey don’t amplify our policies using fake personas, because we don’t want to be seen as creating false grass roots efforts,” the primary protection official mentioned.

One diplomat put it this manner: “Generally speaking, we shouldn’t be employing the same kind of tactics that our adversaries are using because the bottom line is we have the moral high ground. We are a society that is built on a certain set of values. We promote those values around the world and when we use tactics like those, it just undermines our argument about who we are.”

Psychological operations to advertise U.S. narratives abroad is nothing new within the army, however the reputation of western social media throughout the globe has led to an enlargement of techniques, together with using synthetic personas and pictures — generally referred to as “deep fakes.” The logic is that views expressed by what seems to be, say, an Afghan lady or an Iranian pupil may be extra persuasive than in the event that they had been overtly pushed by the U.S. authorities.

The majority of the army’s affect operations are overt, selling U.S. insurance policies within the Middle East, Asia and elsewhere below its personal title, officers mentioned. And there are legitimate causes to make use of clandestine techniques, comparable to making an attempt to infiltrate a closed terrorist chat group, they mentioned.

A key difficulty for senior policymakers now could be figuring out whether or not the army’s execution of clandestine affect operations is delivering outcomes. “Is the juice worth the squeeze? Does our approach really have the potential for the return on investment we hoped or is it just causing more challenges?” one particular person conversant in the controversy mentioned.

The report by Graphika and Stanford means that the clandestine exercise didn’t have a lot influence. It famous that the “vast majority of posts and tweets” reviewed acquired “no more than a handful of likes or retweets,” and solely 19 p.c of the concocted accounts had greater than 1,000 followers. “Tellingly,” the report acknowledged, “the two most-followed assets in the data provided by Twitter were overt accounts that publicly declared a connection to the U.S. military.”

Clandestine affect operations have a job in help of army operations, however it must be a slim one with “intrusive oversight” by army and civilian management, mentioned Michael Lumpkin, a former senior Pentagon official dealing with data operations coverage and a former head of the State Department’s Global Engagement Center. “Otherwise, we risk making more enemies than friends.”

Alice Crites contributed to this report.